While the idea of exploiting resources on the Moon and other solar system bodies has been around for many years, with promises of lunar bases and colonies on Mars, these ambitious dreams have yet to become reality.

The situation might be changing now, however, thanks to the advent of improved technologies, falling costs of space travel and the private sector’s rush to develop competitive energies. Commercial developments in the space industry and the shortage of chemical elements needed for industry also means that we might have to look for resources elsewhere – on the Moon, asteroids or, in the longer term, other bodies further out in the solar system.

A bonanza to mine

The asteroid Psyche (which is about 200 km wide) could be 50% metallic, meaning it could contain the equivalent of millions of years of our annual global iron and nickel production. And it is not only these metals that are attracting future space prospectors.

Other asteroids are rich in elements that are very rare on Earth. These include platinum, iridium, osmium and palladium, which are all extremely important for industry and are used in products as diverse as catalytic converters, pacemakers and medical implants. Importantly, they are also present in most modern electronic components. Since they are a limited resource on Earth, their high cost may make the idea of mining them in space not such a far-fetched idea.

Closer to home, the space industry is becoming increasingly interested in the Moon. Not for rare metals, but for two other equally strategic resources.

The first is water. Lunar orbit analyses from scientific exploration probes such as the US Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and India’s Chandrayaan‑1 have confirmed that water exists on almost the entire surface of the Moon, but especially in the form of ice in craters, permanently in the shade, at the poles. Once purified, this water could initially be used to meet the water requirements of astronauts on a lunar mission. Once it has been separated into its basic constituents (oxygen and hydrogen), however, it could provide spacecraft with fuel (this is what the Ariane 5 rocket’s main stage uses today).

What is more, it appears that solar winds have deposited large quantities of helium‑3 (a light isotope of helium) in the equatorial regions of the Moon. This helium‑3 is a potential fuel source for second and third generation fusion reactors that are expected to come into operation by the end of the century.

An ever-evolving legislative framework

Would we be allowed to freely mine other celestial bodies ?

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty explicitly forbids nations from claiming ownership of a celestial body. The Moon, for example, is a ‘common good’. However, it is easy to find loopholes in this text, which was written at a time of the Cold War when space-related concerns were very different.

One of the ‘ploys’ put forward by the US and other nations that want to develop space mining is that, just as international waters on Earth belong to no one, and that anyone can fish in them, countries and companies could de facto exploit and make their own the resources extracted from celestial bodies – without actually claiming the celestial bodies themselves.

To address these concerns, the Obama administration signed the so-called “Space Act” in 2015, allowing US citizens to “engage in the exploration and commercial exploitation of space resources”.

In April 2020, the Trump administration issued an executive order supporting US mining on the Moon and asteroids. This was immediately followed by NASA’s Artemis agreements in May 2020. These include the development of ‘safe zones’ surrounding future lunar bases, presumably to prevent different countries or companies from stepping on each other’s toes and potentially triggering diplomatic incidents.

We must remember that the United States is not the only country working on new legislation for future commercial space activities. Luxembourg and the United Arab Emirates are codifying their own laws on space resources in the hope of attracting investment with business-friendly legal frameworks. Russia, Japan, India and the European Space Agency are following suite and all have their own space mining objectives.

Private companies on the starting blocks

While the real exploitation of space resources has not yet begun, this new sector is jam-packed with private-sector candidates. These come and go, however, as agreements are made and unmade, funding is found and lost, and companies go bankrupt.

Planetary Resources, founded in 2009 with the aim of developing a robotic asteroid mining industry, fell by the wayside in 2020 despite high-profile founding investors that included Alphabet’s Larry Page, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and Virgin Group founder Richard Branson.

Schakleton Energy Company, a Texas-based company founded in 2007 to develop technologies for lunar mining, failed in 2013 because it was not able to raise enough funds in the two years that preceded this date.

Other companies have emerged since then, however, and are laying their stakes on an important future space industry. One example is Japan’s iSpace, which aims to ‘help companies access new business opportunities on the Moon’ (extraction of water and mineral resources). Offworld, a Californian company, is developing ‘universal industrial robots capable of doing most of the mining on Earth, the Moon, asteroids and Mars’. The UK’s Asteroid Mining Corporation is currently funding the development of the ‘El Dorado’ satellite, officially scheduled for launch in 2023. This satellite should conduct a broad spectral survey of 5000 asteroids to identify the ones most valuable for mining.

Still a long way to go

However interested the public or private sector is in developing extractive activities for extraterrestrial resources, the task will be far from easy.

If we are to mine the Moon, for example, we will have to overcome a number of specific problems. At the lunar poles temperatures go from 120˚C during the day to ‑232˚C at night, and radiation from cosmic rays, which are not deflected by a planetary magnetic field, like that of the Earth’s, creates a very hostile environment. As the Apollo astronauts also discovered, lunar dust is extremely fine and highly abrasive, so moving parts on mechanical machinery must be protected. Lubrication and cooling are very difficult too, as the majority of oils and coolants disintegrate or evaporate in a vacuum.

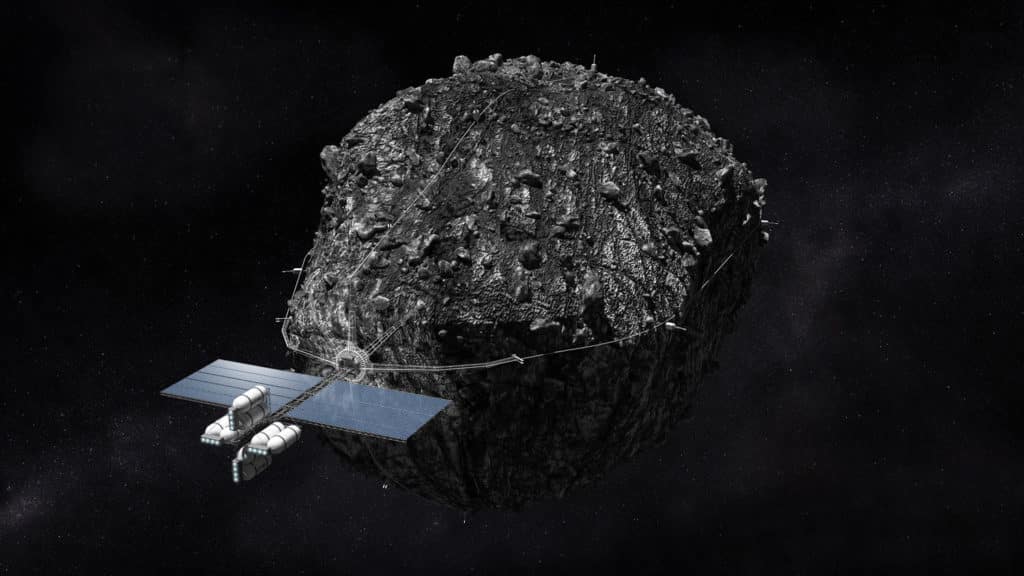

The situation on asteroids in not much better. Although the technologies developed in recent years to reach, fly over and approach the surface of asteroids have evolved considerably, thanks to the development of scientific exploration probes such as Hayabusa 2 (Japan) or Osiris-Rex (USA), the techniques for mining and harvesting materials in zero gravity have yet to be developed and tested.

Finally, we should remember that public bodies are also active in this field. In 2019, ArianeGroup signed a contract with the European Space Agency to study the possibility of going to the Moon before 2025 and start working there. For this study, ArianeGroup and its subsidiary Arianespace have teamed up with a German start-up, PT Scientists, which will supply the lander, and a Belgian SME, Space Applications Services, which will supply the ground segment, communications equipment and associated service operations.