How endocrine disruptors affect brain development

- In the second week after birth, a peak of hormones is secreted from GnRH neurons in a phenomenon known as "mini puberty". It seems to signal to the body that the birth has gone well and that it can continue to grow reproductive organs and a brain.

- Endocrine disruptors – compounds very often found in plastics that resemble molecules of the hormonal system – can affect this process. We are all exposed to these molecules, in varying doses.

- Low concentrations of endocrine disruptors at key moments like "mini puberty" can affect these natural processes, stunting childhood development of the reproductive system and brain.

- Vincent Prevot aims to study the exposure of children during the first 1,000 days of their life and to support families in limiting the presence of toxic substances in their environment.

By disrupting the interaction between neurons and their astrocytes, petrochemical-derived molecules with endocrine activity disrupt both reproductive function and brain development.

The brain is composed of two main families of cells: neurons, which carry out the actual brain activity, and glial cells (notably astrocytes), which modulates how neurones work. This regulation is essential during development of a baby but can be altered by pollutants, such as endocrine disruptors (such as bisphenol A) that have invaded our environment.

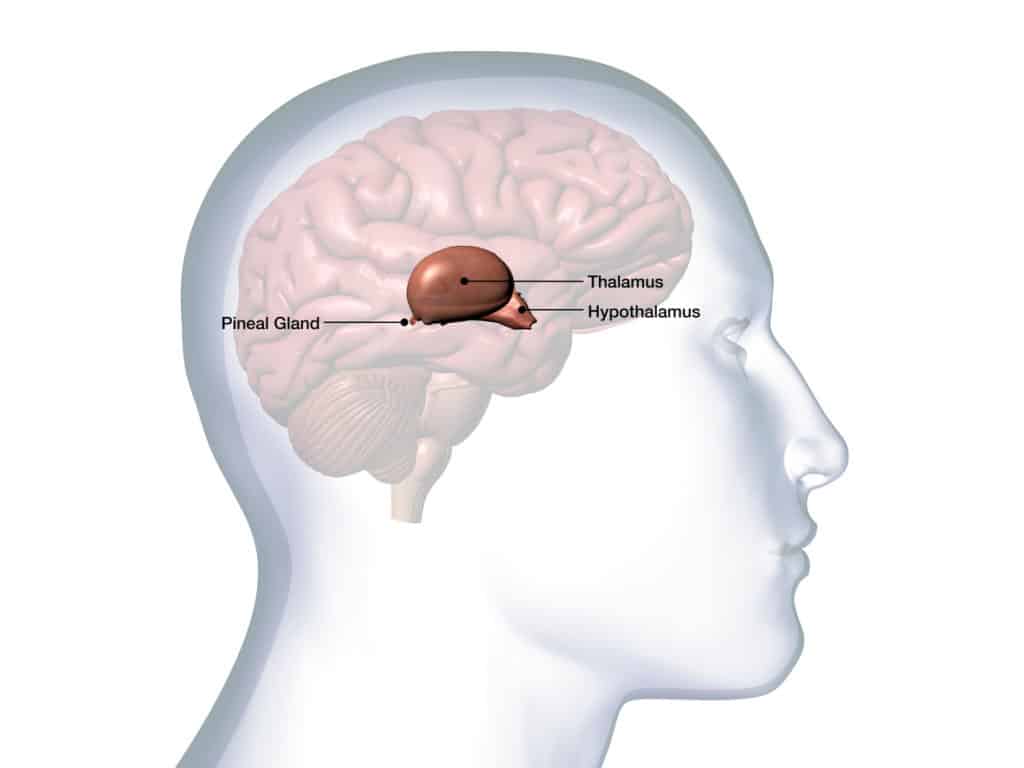

It all takes place in the hypothalamus. This structure, located at the heart of the brain, at the interface between the cortex and the spinal cord, controls the secretion of the gonadotropic hormones, LH and FSH. Their role is to ensure the growth of the gonads in children – in other words, the organs destined to produce sexual hormones.

Once formed, the gonads secrete steroid hormones, which are in turn detected by the hypothalamus. Through this loop, the brain is thus informed about the maturity of the reproductive system. Later in life, after puberty, it is this loop that regulates the menstrual cycle in women and sperm production in men.

Special neurons

The system we are referring to is based on only a handful of neurons in the brain – 2 000 in humans and 800 in mice – that release Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone (GnRH). They are special from birth: as they are not formed in the brain but in the nose. They migrate during foetal life to the hypothalamus. They are also special because of their organisation: unlike most specialised neurons, they do not form nuclei. They are scattered between the olfactory bulb and the hypothalamus. Special because, despite this unconventional organisation, they coordinate and control the secretion of gonadotropic hormones.

GnRH neurons do not work alone. They work together with other neurons, which receive information from the rest of the body and the outside world. In this way, they can put the reproductive function on standby if necessary, so that valuable resources are not wasted at a time that is unfavourable for reproduction.

Glial cells ensure the creation and maintenance of synaptic connections between neurons. This is a crucial but fragile role that plays a critical role in the second week after birth, when GnRH neurons secrete a peak of hormones. This phenomenon is called « mini puberty ». It seems to signal that the birth has gone well and that the body can continue to grow reproductive organs and a brain in general. In the hypothalamus, this is the time when astrocytes stick to GnRH neurons and remain there for life.

A crucial association

This « mini puberty » can be disrupted by premature birth, perhaps explaining the vulnerability of children born too early to non-communicable diseases, such as learning or metabolic disorders. It is also sensitive to the chemical environment. One family of chemical molecules is of particular concern: endocrine disruptors. These are compounds very often found in plastics that resemble molecules of the hormonal system. They alter the communication between organs, for example by masquerading as a sex hormone or by blocking it binding to its receptor.

In rats, studies have shown that exposure to endocrine disruptors prevents the association between astrocytes and GnRH neurons. This results in delayed puberty and fertility problems in adults, but the function of GnRH neurons alone does not appear to be impaired.

What about in humans? This is a question that we are trying to answer thanks to the hospital-university federation project « 1,000 days for health: care before treatment », led by the universities of Lille and Amiens, Inserm, the Jeanne de Flandre Hospital of the Lille University Hospital and coordinated by Laurent Storme. The aim is to study the exposure of children during the first 1,000 days of life and to support families in limiting the presence of toxic substances in their environment.

Other studies have already revealed the importance of the chemical environment on children, in particular those of Anne-Simone Parent in Belgium. With her team, she showed that migrant children, whether adopted or accompanying their parents, triggered early puberty when they moved to Belgium at the age of 5 or 6. It seems that the change in exposure to endocrine disruptors, very present in Africa and Asia (mainly in pesticides), explains this phenomenon. Disruptors block reproductive maturation. When their concentration decreases in the environment of children, this inhibition is lifted, and the brain initiates full puberty.

In contrast, in children born and living in Europe, these products seem to delay puberty. Their action is complex for several reasons. On the one hand, we are all exposed to different molecules, in varying doses. It’s a chemical cocktail that needs to be understood. Secondly, because of their interaction with the hormonal system, they do not act in a linear way. Their activity is described by a U‑shaped or inverted U curve. The effect seems to be maximal for low concentrations, especially during windows of vulnerability, such as « mini puberty ».

Like ours, studies are underway that are difficult to conduct in a context where exposure is unavoidable, and to interpret because of the variable effects over time according to the cocktail. But we are are not limited to analysing the effects of this type of pollution on reproductive functions. As we have explained, brain maturation is closely linked to gonadal maturity. Endocrine disruptors are thus the main suspects in the autism epidemic observed in the United States. We hope that elucidating the mechanisms of action of these pollutants on the brain and development in general will help society to protect itself better.

Interview by Agnès Vernet

For more information:

- GnRH neurons recruit astrocytes in infancy to facilitate network integration and sexual maturation. Pellegrino et al., Nature Neuroscience 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021–00960‑z

- Cellular and molecular features of EDC exposure: consequences for the GnRH network. Lopez-Rodriguez et al. Nature Rewiews 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020–00436‑3