This article is part of our special issue « Quantum: the second revolution unfolds ».

Laurent Sanchez-Palencia and his team are interested in understanding the organisation of matter at the quantum scale, where both wave and particle effects, such as interference and entanglement, are interwoven, as well as strong interactions between particles. Laurent Sanchez-Palencia is also involved in developing new training programmes in quantum technologies at the École Polytechnique and the Institut Polytechnique de Paris.

His team is currently working on quantum simulation to model and understand the behaviour of ‘quasi-periodic’ materials at low temperatures. These materials are too complex to be fully described at the atomic scale and could be better understood using quantum simulation. Other examples include high-temperature superconductors and quantum magnetism.

The theoretical results obtained for minimal models can be tested in real experiments in controllable systems known as ‘optical lattices’. These are made up of atoms at extremely low temperatures – on the order of a few tens of billionths of a Kelvin – and held together by laser beams. When the right number of laser beams point in the same direction on a plane, the result is an exotic system, halfway between order and disorder (ordered over a long-range but non-periodically ordered), something that is known as quasi-periodic.

“Bose glasses”

Researchers are studying what happens when interactions between atoms lead to the appearance of new quantum phases called Bose glasses. These glasses are a special type of insulator that, in theory, should only appear in structures that are either disordered or quasi-periodic. A standard insulator has an energy gap between its fundamental state and its first excited states. This means that only a powerful electric field can excite the charges and set them in motion. In a Bose glass, on the other hand, there is no such energy gap, but the charges are confined to very localised regions that do not allow for a current of particles to flow.

Bose glasses were first predicted at the end of the 1980s, but have never been observed unambiguously in an experiment, even in systems of cold atoms. Indeed, cold atoms are never perfectly cold and, even at temperatures as low as a few billionths of a Kelvin, thermal fluctuations can destroy quantum phases. However, Laurent Sanchez-Palencia and colleagues recently predicted a situation in which, despite these thermal fluctuations, a Bose glass could be stabilised and observed. They are currently discussing with their experimental colleagues how to design an experiment in which they could actually observe these exotic glasses.

These systems are fascinating in many ways. For example, they are often non-ergodic, as opposed to conventional ergodic. Ergodic systems explore all the space at their disposal and can thus reach thermodynamic equilibrium, a situation well described by Boltzmann’s theory, developed at the end of the 19thCentury. Indeed, the behaviour of ergodic systems is compatible with most of the observations made to date on objects ranging from the size of a micron to that of stars and galaxies. This theory is based on the idea that the system fluctuates between all possible states along paths that allow it to move very quickly from one state to another. In non-ergodic systems, on the other hand, this ergodicity is prevented by inhomogeneities in the system. The system remains therefore trapped in a subset of its possible configurations, far from equilibrium.

Entanglement for cryptography

Entanglement is another purely quantum phenomenon of interest to the team. Here, two or more particles can have much stronger correlations than classical physics allows. For example, the observable properties of a quantum particle are generally indeterminate, so that measurement results are random. However, when particles are entangled, determining the state of one particle instantaneously fixes the state of the other(s), regardless of the distance between them. This powerful “spooky action at a distance”, as Einstein called it, seems to transcend space and time, so that we can determine the state of one particle simply by measuring that of its entangled partner. For example, if you measure the spin of one particle, say an electron, you can determine the spin of the other without ever observing it.

We are only just beginning to exploit the applications of this spectacular correlation-at-a-distance effect, even though it is already used in the cryptography of certain telecommunications. In simple terms, suppose that the sender and receiver share an entangled pair, so that the results of their measurements are random but identical. To intercept the communication, an eavesdropper has to perform a measurement, the result of which is random but, more importantly, changes the state of the pair, which is no longer entangled. The measurements of the sender and receiver are no longer correlated, and they can verify this by comparing the results of their measurements. The strength of such an encryption method is that it is not based on the difficulty of spying without being detected, but on an impossibility based on the fundamental laws of the quantum world.

Another application of the random nature of the measurement is the possibility of making perfect random number generators and totally random cryptographic keys.

On the way to commercialisation

These random number generators are already on the market and there is even at least one example of a mobile phone that uses quantum technology of this type. Quantum entanglement can also be exploited in a process known as dense coding, which is linked to the fact that an entangled state contains a phenomenal amount of information compared with the information carried by each individual particle.

Each particle contains information about its own state, but the information on correlations is distributed among all the infinitely larger subsets of particles. This effect makes it possible to encode an immense quantity of information in structures called quantum bits, or qubits. These differ from standard computer bits, which can take the value either 0 or 1. Qubits, however, can take both values at once, or any combination of 0 and 1.

The importance of the “quantum advantage”

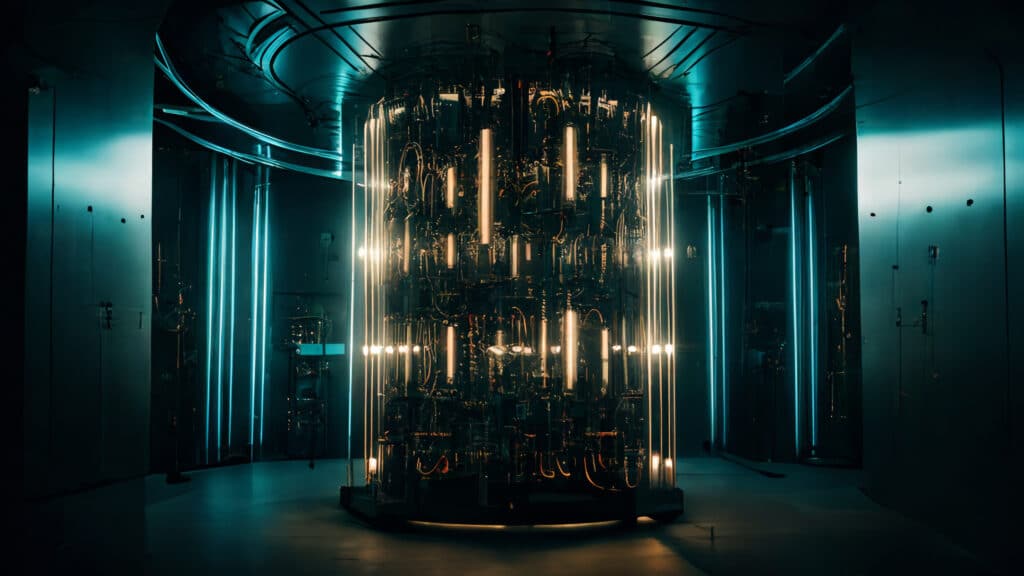

Qubits are the basic building blocks of future quantum computers. Exploiting their quantum properties, in particular entanglement, can be applied to solve complex computational problems, making it possible to perform certain computational operations much faster than the most powerful computers available today. This would result in an exponential increase in computing power. Qubits can be fabricated from a variety of currently available material platforms, such as superconducting qubits or trapped atoms and ions. Other future methods include photonic quantum processors that use light.

Spectacular progress has been made in recent years. However, a real ‘quantum advantage’ is not expected until quantum computers are operating with – depending on the estimate – between a few hundred thousand and a few million qubits. We only know how to build machines with around a hundred qubits today, so there is still a long way to go.

We only know how to make machines with a hundred or so qubits today.

The main obstacle to progress is quantum decoherence. This results from the interaction of qubits with their environment, which destroys their entanglement. To avoid this – or at least limit it – it is generally necessary to operate qubits at a temperature close to 0 kelvin and protect them from the environment. From a fundamental point of view, there is nothing to prevent the creation of large-scale quantum computers, but there are still scientific questions to be resolved, such as whether decoherence can be fundamentally countered. Important engineering problems also need to be overcome. Projects to solve these are being funded by important government programmes and private investment around the world.

In the shorter term, hopes are being pinned on machines that are less sensitive to decoherence. These are quantum simulators, which can be seen as dedicated quantum computers with an architecture that optimises certain specific tasks. Quantum simulators are particularly well suited to the search for ‘minima of multivariable functions’. Such machines are therefore of interest to companies that use complex networks and seek to optimise them. These networks contain a large number of variables and a quantum simulator could optimise them in a way that a conventional computer cannot.

Most of the necessary technology already exists, but the question remains as to which computing problems quantum simulation could be of real economic interest. These technologies are still very expensive and consume a lot of energy. The question is more open than we might think, but current advances are paving the way for a host of radically new technologies. The message that Laurent Sanchez-Palencia is trying to get across to his students is that we need to think not only about quantum computers, but also about all the associated technologies. These may seem less spectacular at first glance, but they will very likely give rise to new technologies.

Quantum training at École polytechnique

There is an urgent need for training at all levels in the field of quantum mechanics. For many years, physics teaching at École polytechnique has focused on this subject. As a result, all students, including those who do not intend to go on to study physics or engineering, are trained in this discipline during their first year of study. We are already reaping the rewards: many of the start-ups being developed in France today in the field of quantum mechanics are run by former students of the École polytechnique.

In order to anticipate the development of quantum technologies, the Quantum Science and Technology course was created a few years ago: it focuses on the most modern aspects of quantum physics, in particular entanglement and how this effect can be exploited. The course emphasises the link between fundamental science and technological development, because at present, despite what we may read in the press, quantum physics is still at the development stage, and there is still much to understand.

The Master’s and PhD programmes are run in close collaboration with the other schools on campus, within the Institut Polytechnique de Paris. They aim to recruit the best students from the best institutions around the world. Students who join the institute for a Master 1 directly join a research team at IP Paris to reinforce links between training and research. In addition, IP Paris recently started offering continuing education courses for professional engineers who have never studied quantum science. This training is also important for start-uppers who need very specific technical skills to develop particular devices and for managers of companies, whether they are SMEs or larger.

An important aspect of the development of quantum research at IP Paris is that it is being carried out hand in hand with the Université Paris Saclay within the Institut Quantum-Saclay. This allows the two institutions to take advantage of their complementary strengths. At the national level, a new consortium was created last year, funded by the French National Research Agency.