This article is part of our special issue « Quantum: the second revolution unfolds ». Read it here

Quantum physics, which explains the behaviour of atoms and other even smaller particles, is the basic structure that enables us to deduce the physical behaviour of matter, not only on a microscopic scale, but also, in theory, right up to the human level. After all, aren’t we just a large assembly (albeit an extremely complex one) of atoms and molecules, all of which obey the laws of the infinitesimal world?

In reality, the situation is different. Just as you don’t need to know the subtleties of fluid mechanics to pour yourself a glass of water, you don’t need to have a detailed understanding of the interaction of the 1028 atoms in your body to start taking care of yourself. As such, quantum physics is very much a part of modern medicine: let’s see how the infinitely small helps us to maintain good health on a daily basis.

A scalpel made of light

It may seem surprising, but one of the most precise tools available to modern medicine is… light. Or, to be more precise, a beam of light that is perfectly calibrated to ensure that all the photons have the same energy and that all the light waves are perfectly coherent with each other: the laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation).

This extremely precise control of light emission comes from the fact that, according to quantum mechanics, atoms have distinct (quantified) energy levels and that by making electrons jump from one precise orbit to another, only perfectly identical photons are emitted.

First predicted by Albert Einstein in 1917 and perfected in 1960, the laser immediately found medical applications in ophthalmology (Campbell, 1961) and dermatology (Goldman, 1963). Today, it is used to treat retinal detachment, coagulate wounds, destroy small cancerous tumours, cut and abrade corneas with extreme precision and, in dental surgery, to treat gum disease.

But in addition to its applications in surgery, this technology can also be used for lighter treatments such as tattoo removal, anti-wrinkle treatments and laser hair removal.

Examining the body with the help of nuclear physics

One of the most widely used imaging techniques is MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). It involves observing the behaviour of the nuclei of hydrogen atoms immersed in an intense magnetic field. Why hydrogen? Because it is the main component of water (H2O), which accounts for around 60% of the total mass of a human being, and there are few other biological molecules that contain no hydrogen at all.

The principle of MRI is as follows: the hydrogen nucleus is made up of a single proton which, for this purpose, can be regarded as a tiny magnet. In a ‘natural’ situation, the human body has no particular magnetisation, and each hydrogen nucleus points in a random direction.

The first step is to immerse the patient in an extremely intense magnetic field (around 30,000 times the Earth’s natural magnetisation) to ‘arrange’ all the protons in the same direction, all parallel to each other. This balance is then altered by emitting a radiofrequency (RF) wave, and we listen to the RF wave emitted back by these protons when they return to their initial state.

Depending on the nature of the medium, these protons will not return to their initial state at the same speed. In this way, we can reconstruct a 3D image of the body by differentiating between each tissue. Without quantum physics and a detailed understanding of the behaviour of atomic nuclei in an electromagnetic field, this advanced non-invasive imaging technique would not be possible.

Matter in all its states

Even the most unusual states of matter, which are still the subject of fundamental research in laboratories around the world, are essential for medical imaging. As mentioned above, MRI requires the patient to be immersed in an extremely intense magnetic field. The higher the field, the stronger the signal emitted when the magnetisation returns to its normal equilibrium, and the better the image quality.

Superconductivity is one of the rare manifestations of matter behaving in a purely quantum manner on our scale.

The problem is that these magnetic fields are so intense that if we were to use a conventional electromagnet to generate them, the amount of heat caused by the intense electric current required would melt them in a matter of moments.

To overcome this problem, we use so-called « superconducting » magnets, which have zero electrical resistance. With magnets of this type, no electrical heating occurs. Electric currents can potentially be passed through them as intensely and for as long as required (without any loss of current, even when the power supply is cut off).

Superconductivity is one of the rare manifestations of matter behaving in a purely quantum manner on our scale. The electrons behave like a single superfluid and flow without any resistance. These superconducting elements are also used in magnetoencephalography to record the brain’s electrical activity non-invasively and in real time.

Antimatter to the rescue

How can we find out where cancerous areas are located in the human body and how they develop over time? To do this, we use the hyperactivity of cancer cells. Cancer cells divide constantly and anarchically, so they expend a lot of energy. Their fuel: sugar.

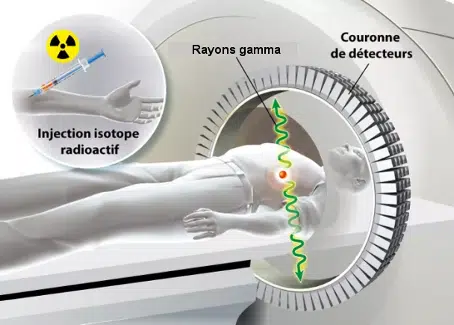

This is why, during a PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan, the subject is made to swallow sugar whose composition has been slightly altered. A radioactive atom (e.g. Fluorine 18) is attached to each sugar molecule, and when it decays it has the property of emitting an anti-matter particle: an anti-electron (also known as a positron).

By reconstructing the trajectory of these gamma rays, we can find the location where these matter-antimatter reactions took place, and therefore the position of the cancerous tumours.

Sugar will accumulate in places that consume a lot of energy (tumour areas), and emit antielectrons that, when they come into contact with the ‘classic’ electrons of the surrounding matter, will annihilate and produce gamma photons that pass through the body and are detected outside. By reconstructing the trajectory of these gamma rays, we can find the location where these matter-antimatter reactions took place, and therefore the position of the cancerous tumours.

Ingenious and, once again, impossible to achieve without understanding the particle physics behind this medical imaging technique.

Quantum physics is an integral part of our daily lives, and as such it has also entered the field of medicine, without which a large proportion of modern treatments and imaging techniques would not be able to function. Far from being confined to research laboratories, quantum physics, particle physics and nuclear physics save many lives every day.