Hydrogen is in fashion. Several states and companies are placing their hopes in this chemical element to fight against global warming. Not a week goes by without a new enthusiastic announcement for this gas as a source of energy: a hydrogen-powered bus for the company Transdev, a hydrogen and fuel cell utility vehicle unveiled by Citroën, or a cross-border hydrogen network between France, Germany and Luxemburg.

Admittedly, at first glance, hydrogen (H2) is pure gold – so to speak. When it is burned or used with a fuel cell, you get thermal or electric energy and water without polluting. Yet, its current production emits a lot of CO2. To really turn it into green fuel, major investments in R&D will be needed, in combination with strong regulatory incentives.

Hydrogen production emits CO2

While hydrogen a major constituent of the universe, on Earth hydrogen atoms hardly exist in the pure H2 gas-state that industrials use and as we discuss in this braincamp. Therefore, it cannot be used as an energy source, rather it is an energy carrier – like electricity. This means that hydrogen production requires input from other sources of energy which potentially emit CO2.

Today, hydrogen produced through methane reforming, a production method emitting CO2, costs about 1€ per kilo, versus 4 – 6€ per kilo when it is produced through electrolysis. Due to the law of supply and demand, 95% of hydrogen is therefore produced using fossil fuels. The remaining 5%, produced through electrolysis could be “green”, provided that the electricity used is also carbon-free (renewable or nuclear energy), which is not always the case (especially with coal-fired power plants). Seventy million tons of hydrogen are produced per year in the world, releasing 830 million tons of CO2, that is to say 2% of global emissions – a rate similar to that of the air transport sector.

So why is hydrogen so popular? Because in the long-term, it seems to be one of the possible substitutes to fossil fuels. Industries generating large amounts of CO2, like the metal or glass industries, might benefit from hydrogen. In theory, it could also revolutionise the transportation sector: hydrogen-powered vehicles do not emit exhaust pollutants and their widespread use could limit pollution in cities. Finally, in the future, the energy mix might rely on hydrogen to store electricity produced by intermittent renewable energies (wind or solar energy).

Storage, security, cost… challenges remain

It is difficult to make reliable predictions because the future of hydrogen will depend on many factors: cost and availability of fossil fuels, regulation of CO2 emissions, financial incentives for clean energies. Nevertheless, we can foresee four main markets for hydrogen: (1) optimisation of the electrical grid when we achieve intermittent energy sources; (2) self-consumption at the local level for areas which are not connected to the electrical grid; (3) development of hydrogen-powered electric vehicles; and (4) industry.

This gas has indeed been used for decades in industry (mainly for petrochemical processes, steelworks, and the production of nitrogen fertilizers). We know how to produce hydrogen, transport it in pipelines, and safely use it. Yet hydrogen-energy still poses many complex challenges. How can we produce it in a cost-effective and environmentally sound manner? How can we safely use it in everyday life, and not only in industry? How can we store it in cars, buses or planes, given that it must be stored under high pressure? How can we adapt infrastructures if the current gas pipes are inadequate? How can we improve the yields of energy transformation?

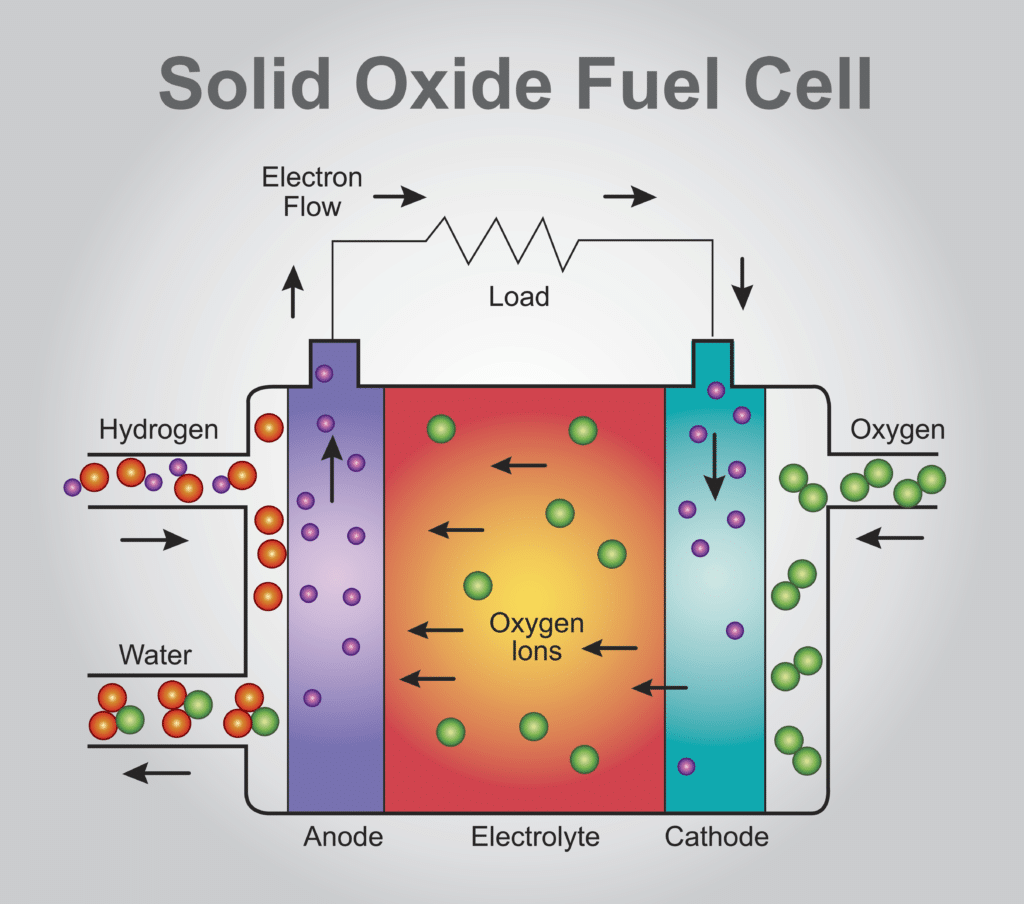

As we have said, hydrogen is above all a way to store electricity. In the case of renewable energies, for example, electricity production during periods of strong winds or sunny weather by wind turbines or solar panels does not always match consumption. This electricity must therefore be stored, but current batteries are mainly adapted to short-term storage. Hydrogen developers thus suggest using this electricity to produce hydrogen through electrolysis, store this hydrogen as long as necessary, and then convert this hydrogen into electricity with a fuel cell. But for the moment, the overall performance is only 25% 1. Can we afford to waste three quarters of the electricity produced?

All these challenges can only be overcome on two conditions. First, an unprecedented R&D effort to remove roadblocks. But also, financial incentives: at this time, and given the production costs, it is difficult to see how green hydrogen produced by electrolysis could capture market shares without running the risk that companies begin producing it at the expense of carbon-emitting methods.

A bit of chemistry to understand hydrogen production

Methane reforming consists of reacting methane (natural gas) with steam, in the presence of a catalyst. The equation of the chemical reaction shows that this method inevitably produces CO2:

CH4 + 2 H2O → 4 H2 + CO2

We therefore produce one molecule of CO2 for 4 molecules of hydrogen (to be accurate, we ought to speak of dihydrogen molecules).

The production of hydrogen from coal is even worse:

C + 2 H20 → CO2 + 2 H2

Only two molecules of hydrogen are produced for one molecule of CO2.

In contrast, water electrolysis does not produce CO2:

2 H2O → 2 H2 + O2

But this reaction requires large amounts of electricity.

The pyrolysis of methane (see the interview of Laurent Fulcheri) consumes methane, but unlike reforming, it does not produce CO2. It still requires electricity, but 4 ‑7.5 times less than electrolysis.

CH4 → C + 2 H2

For further reading

- The report on hydrogen by the International Energy Agency (June 2019)

- The report by Ademe on hydrogen as a source of energy (August 2020)

- « Le rôle de l’hydrogène dans une économie décarbonée » by the Académie des technologies, November 2020

- The national strategy to develop carbon-free hydrogen in France