“To understand, we must observe,” that’s the motto of modern structural biology. It is a field that aims to obtain the structure of biological objects to better understand the role of a particular molecule in a cell. This modern structural biology was born in 1953 with the publication of the structure of the DNA double helix by Watson and Crick1 and a few years later with the first protein structures by Kendrew and Perutz. Since then, structural biology has provided researchers with valuable information for understanding and protecting life.

A complex history

Techniques available for resolving the 3D structure of biological objects become available and evolved in turn. X‑ray crystallography, already mastered in the 1910s, underwent a revolution in the 1990s thanks, among other things, to the use of crystal cryogenics and the quality of synchrotrons that generate X‑rays. Nuclear magnetic resonance, discovered by chance in the 1940s, emerged in structural biology in the 2000s and is still used today, especially to study the dynamics of proteins. For a long time, electron microscopy (which was born in the 1930s) was considered in biology as a pair of binoculars to see the infinitely small but without providing high-resolution structural information.

The problem: the molecules of living organisms are miniscule. For example, the SARS-CoV‑2 Spike protein weighs ~180–200 kDa2 – equivalent to three haemoglobin molecules3. Electron microscopy images have a lot of noise due to the interaction of the electron beam of the microscope with the sample. As a result, nothing can be seen on the images if the object observed is too small. It is only in the last ten years or so that a revolution has taken place. The design of microscopes has been improved. Also, the quality and speed of the detectors used have made it possible to record better quality images, the software used to help process the data is more intuitive and more efficient, and the speed of certain calculations has been improved by a factor of 50 thanks to computer graphics cards. If the SARS-CoV‑2 pandemic had appeared some 15 years ago, we would never have been able to obtain its structure so quickly and so precisely!

Better and faster

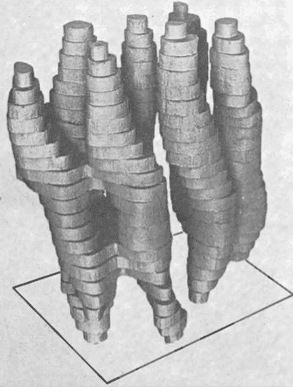

Electron microscopy originated in Germany and was first used in physics. Biology benefited from developments in physics and the first images of biological samples date from the 1950s. It was not until 1968 that the Americans Rosier and Klug demonstrated that 2D images taken with an electron microscope could be used to trace the 3D structure of the object studied. The first structure of a membrane protein came from a bacterium. It dates back to 1975 and was made by British pioneers Unwin and Henderson (see photo below). Henderson received a Nobel Prize in 2017 for his pioneering work over 40 years with researchers Frank and Dubochet.

It took another 40 years to obtain the almost-atomic resolution (3Å average resolution) of the human ribosome (made up of several strands of RNA and about fifty proteins). Today, more than 10 structures per day are deposited in researcher databases and more than 20% of them are high-resolution data.

As early as January 2022, the precise structure of the Spike protein of the omicron variant of SARS-CoV‑2 (which only appeared in November 2021) and its human target (the ACE2 lung receptor) was revealed. This has led to new strategies to fight more effectively against the infection of this virus in our lungs6. Also, knowledge of the exact arrangement of the amyloid fibres involved in Alzheimer’s disease has made it possible to design drugs that slow down the accumulation of these fibres in our brain7. Thus, more and more biological models are being revisited and rapidly improved thanks to high-resolution 3D structures obtained with the latest advances in electron microscopy. Technological barriers are opening up to now observe proteins alone or in complex with other partners to better understand their role in the cell. No wonder the pharmaceutical industry is investing heavily in this technique to screen their new therapeutic molecules more easily and quickly!

The limits of the technique

An electron microscope operates in an ultra-high vacuum (10-8 mbar) so that the electrons flowing through it generate as little extraneous noise as possible. The only way to observe a biological sample is to transform it into a solid ice cube (by vitrification) so that the sample, once in the microscope, remains in solid form while retaining its original shape: this is what is known as cryo-EM!

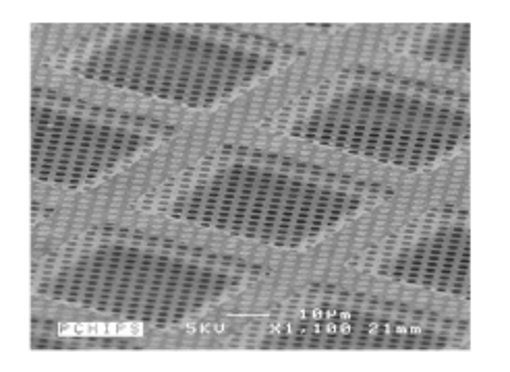

The support on which the sample is deposited is, in general, a perforated carbon membrane of about 10 nm thickness which rests on a copper framework forming tiles of about 100x100 µm. The sample will be trapped in the holes of the perforated membrane and the most critical step is to form a thin film in each hole. The copper framework is a standard 3mm diameter grid. This grid is then placed in the electron microscope.

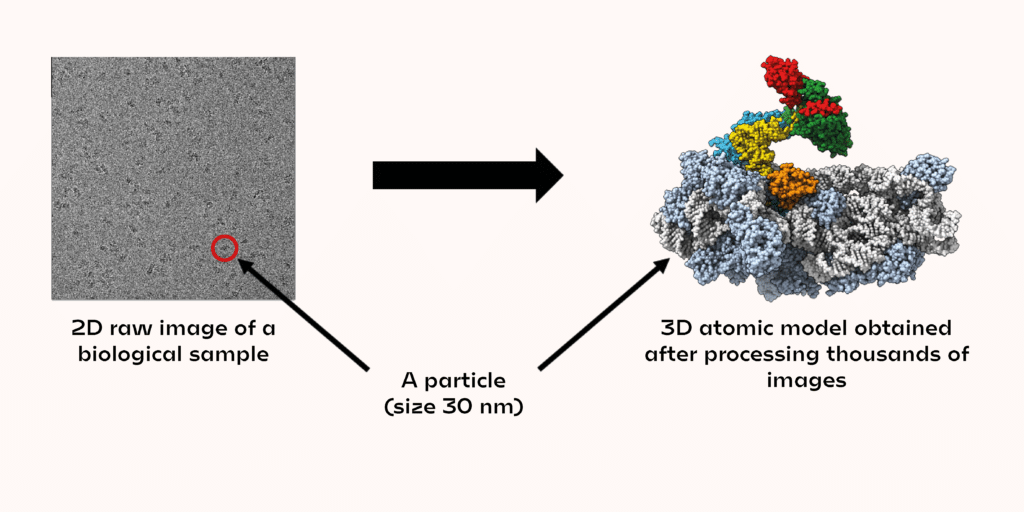

The electron beam used (generated by the electron microscope) will pass through the sample on the grid. The images recorded by transmission will provide information on the 3D organisation of the atoms that the beam encounters, but they also generate a lot of noise. This is why it is necessary to record thousands of images to average the information and obtain a good signal-to-noise ratio, in order to unambiguously determine the shape of the biological objects studied.

In each image, a few dozen biological objects (called particles) can be seen. The shapes observed in the images correspond to different projections of the same 3D object. A projection contains all the structural information to trace the atomic coordinates of the 3D object. The images must then be analysed to match the rotation angles applied to the original 3D object, to obtain the observed projection in the microscope. By collecting a large amount of data, it is possible to obtain the 3D structure of a biological object on an atomic scale. So, research that used to take several months now takes only a few weeks or even days.

Not every biological sample can be observed with an electron microscope yet. At present, objects smaller than 20–25 kDa (about 3 nm) are very difficult, if not impossible, to observe. But this is where the other structural approaches described at the beginning can fill this gap!

One of the laboratories at École Polytechnique (BIOC) is a pioneer in its field, using the electron microscopy approach to study, among its various research topics, the ribosomes of Archaea. The preliminary data for the work published910 were carried out at CIMEX (see box).

Another revolution on the way?

Over the past decade, major revolutions have taken place in the design of microscopes, in the camera technology used to take images and in the software used to process these images. This discipline has been brought up to date and has radically changed the way researchers approach biological problems.

The next step is to see the molecules in their cellular context. Electron tomography is still a traditional method that requires a lot of know-how and is not very popular. The preparation of the samples is even more critical: it requires us to be able to cut a thin lamella of about 200 nm thickness out of a cell ice cube. This slide is then observed at different angles in the microscope to calculate a 3D map of the region of interest at medium resolution. Computers are then able to recognise profiles of molecules in this 3D map to reconstruct a model of the 3D map. There are many developments in this field and in a few decades it should be possible to look at a particular protein anywhere in the cell in its cellular context. The nano-universe of cells will soon hold no secrets for us…

CIMEX

The Centre Interdisciplinaire de Microscopie Electronique de l’École Polytechnique (CIMEX) is a platform housing several microscopes where physicists, chemists and biologists can meet and use high-performance electron microscopes. One of the microscopes, called NanoMAX, is a world prototype. It is used by physicists and chemists to study, among other things, the growth of carbon nanotubes at high resolution and in real time. The other microscope used more by biologists, called Nan’eau, is versatile and well-equipped. It allows important preliminary data to be obtained before moving on to state-of-the-art microscopes (available at 3 national reference centres). The images then recorded will be of sufficient quality to obtain the high-resolution 3D structure of the object studied.