Medicine isn’t just about drug treatments. Differences between patients are not limited to genetics. At MΞDISIM, researchers are analysing the biomechanics of diseased tissue to create digital models for individual patients as a way better guiding therapeutic choices.

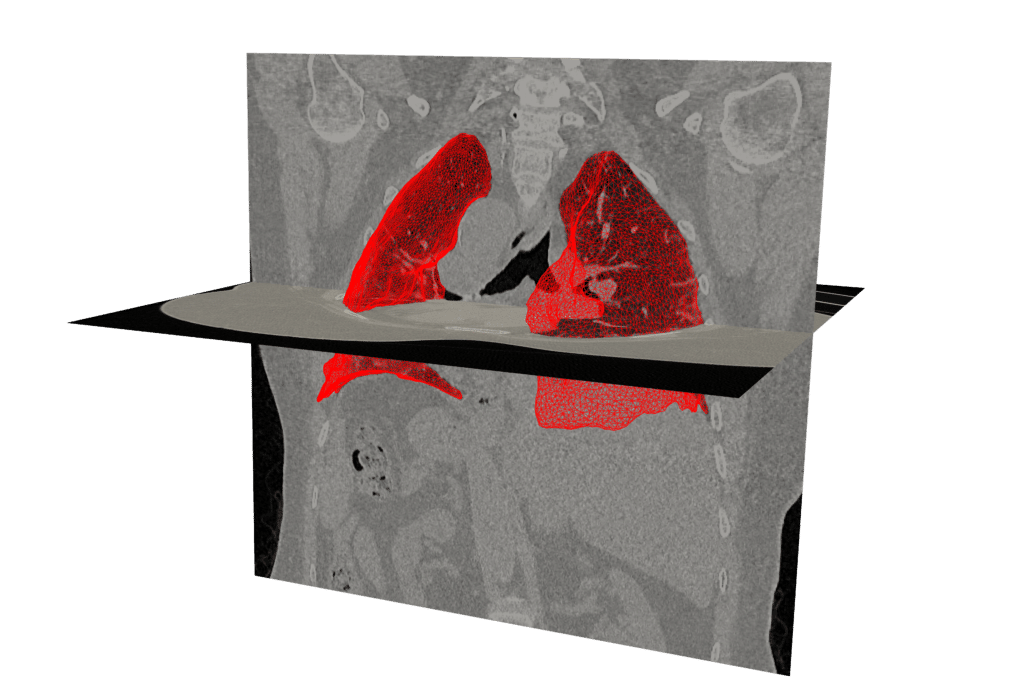

“The lung changes shape when we breathe, and doubles in volume”, Cécile Patte, a researcher and recipient of the 2020 L’Oréal-UNESCO for Women in Science Award who recently defended her doctoral thesis at MΞDISIM, points out. “The way it changes shape depends on its mechanical properties, such as elasticity.” She developed a digital lung model in order to help doctors at Avicenne Hospital in France to better understand the individual characteristics of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – a chronic lung disease, which is one of the long-term effects of Covid-19.

In this condition, scar tissue forms in the lungs, rendering them stiff, blocking the passage of oxygen to the blood and leading to fatal respiratory failure within just two to five years. Significantly, the shape, porosity and mechanical properties of the lung are not the same for all patients. “In order to answer general questions, you only need a model of an average lung, using average measurements for the mechanical properties. But for a personalised approach, you need to build an avatar of the patient’s organ,” she explains. This means acquiring data.

Real life data

“We want to work with existing data, although it makes things more difficult. We don’t want to subject patients to extra invasive procedures in order to create the avatar,” Patte says. The models are therefore based on data collected during the normal course of the patient’s treatment. Exams vary depending on the kind of pathology and the organ in question. For the heart, there are blood pressure and electrophysiology measurements. For the lung, it’s mainly imaging techniques, X‑rays and scans. “If we could measure pulmonary pleural pressure, for example, the model would be more accurate, but the test is too invasive.”

The patient’s specific information is fed into a digital avatar, enabling more detailed diagnosis, which includes quantifying mechanical parameters, evaluating potential treatments and predicting prognosis. “This information should help doctors better diagnose the disease and guide the patient towards drug therapy or transplantation.”

Currently, personalised simulation is only at the research, or ‘proof of concept’, stage. Much work still needs to be done before it can be applied clinically and used as a medical device to help make therapeutic decisions. The regulatory environment is strict and subject to EU requirements, such as CE marking.

So far, Patte’s lung simulation software has only been applied to four patients. “Using the computing capacity of the lab’s server cluster, our software needs up to three full days to process one patient’s data,” she admits. Processing time will have to be shortened for the system to work in clinical practice.

A digital twin

The lung is not the only organ the team is modelling: a lot of work is being done on the heart with multiple clinical applications, and in direct collaboration with various hospitals. The aim is to represent the heart and its various characteristics, including size, contractility and electrophysiology. Personalised cardiac models could enable doctors to test out a treatment virtually, particularly in the case of heart failure, and predict whether or not the patient would respond.

MΞDISIM has also designed a tool, AnaestAssist, to monitor the cardiovascular system in real time while a patient is anesthetised. This software models the patient’s cardiovascular physiology in order to predict the effects of the anaesthetic and assist the doctor during the operation. Other laboratories throughout the world are working on modelling blood flow, bones, kidneys, etc. Patte believes that “all organs can be studied with this approach.”

It may one day be possible to bring all these models together in order to simulate systemic effects and create full digital twins of patients to help pinpoint individualised treatments. This idea has even gained ground in industrial circles, with investment from companies such as Dassault Systèmes, who created a platform called 3DEXPERIENCE that can help medical device manufacturers optimize product development through simulation.