By definition, each individual is unique, which makes clinical research complicated. Clinical trials on volunteers are conducted to ascertain the efficacy of a particular medication. But because not everyone reacts in the same way to the same treatment; effects are difficult to measure. Some volunteers experience clear benefits, while others seem impervious, or undergo a negative reaction. In order to understand the effect of a drug, we must therefore understand this variation between individuals, and Marc Lavielle is rising to that challenge.

With the aid of mathematics, he is helping doctors and biologists improve their understanding of the drugs they test. “I analyse data from clinical trials, often from the initial phase involving few patients. My colleagues and I then model the drug’s pharmacokinetics,” he says. Through algorithms and statistics, he is able to reproduce the effects of the drug in the body via computer simulation. “The second phase can then be optimised, increasing the chances of significant results.” The risk of failing to ascertain whether or not a drug is effective after several weeks of clinical trials is one of the major drawbacks in clinical research.

Lavielle believes that a better understanding of individual variation could help avoid this problem. The goal is to figure out how to select patients who will react best to treatment and avoid those likely to experience side effects. But this is no easy task. We need to understand the biological signals, and which genes indicate how a patient may react. Understanding these effects is central to personalised medicine: once the drug is authorised, doctors would prescribe it only to those who are likely to respond well.

Integrating individual variation

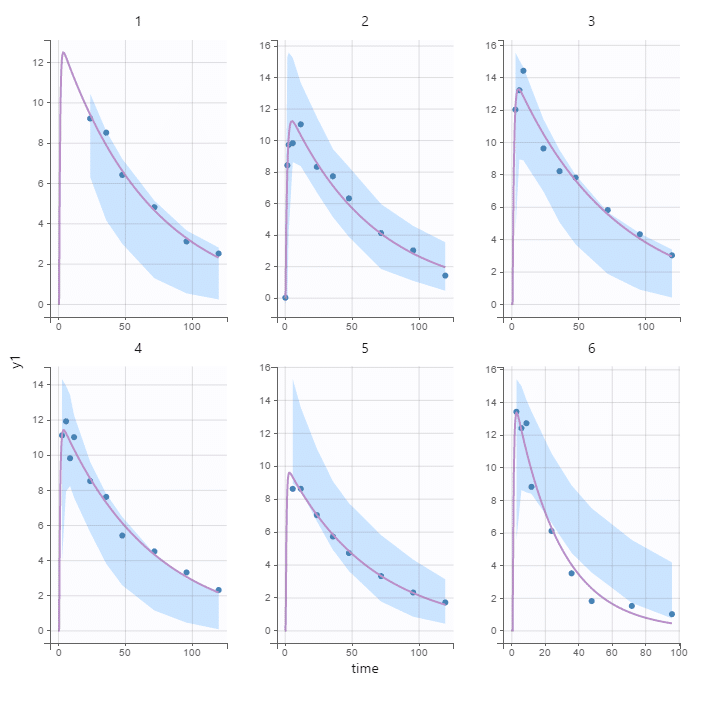

Lavielle’s work uses mixed-effect models that can be represented graphically. “All the models have the same layout,” he explains. “They represent how the drug is absorbed and distributed throughout the organism, metabolised and, finally, eliminated.” But models vary from individual to individual: some people absorb the drug slower; others eliminate it more quickly, and so on.”

Sometimes these differences can be explained by conventional medical criteria, such as the patient’s weight. But with new DNA sequencing technology, we can now identify other, genetic variables. “Pharmacogenetics uses genetic data to understand why some patients respond to a certain treatment while others don’t,” Lavielle adds. “The success of a model depends on our ability to understand variations between individuals.”

In order to do this, he feeds biological data into his mathematical tools. “It is vital to work with experts in the field to interpret results and use criteria that make sense from a biological standpoint,” he stresses.

Optimising clinical research

The terms of the problem are set; all that is needed is the right formula to describe the effects of a drug or the development of a tumour over time, while taking into account the way these processes vary from one individual to another. This is the work of the mathematician. Once this is done, he can present his simulation tool to doctors.

“Using these models, we can generate virtual patients and simulate their response,” he says. This means we can create virtual clinical trials. “The advantage of virtual patients is that we can give them any treatment without causing harm. We don’t have to worry about ethical constraints. Above all, it saves a great deal of time!” A digital model can run in a matter of seconds, whereas phase one of a real-life trial – where drug tolerance is assessed to help define dosage and frequency for subsequent trials – may take one to two years.

These models can be used in all clinical trials, in or outside of personalised medicine. “But when they are built using data from a phase 3 trial [evaluating treatment efficacy], we get a really good description of how the drug behaves,” he adds. “By combining clinical data from a patient with that from clinical trials, we will be able to predict their response to treatment.”

Predicting patient response

This could enable us to identify patients likely to respond to a treatment, and those who may have side effects or develop resistance, which is crucial information for clinical applications. There is one pressing problem – more mathematicians are needed in the medical field. No wonder biopharmaceutical giant Sanofi has been funding the Numerical Innovation and Data Science for Healthcare sponsorship program at École polytechnique since December 2019!

At the same time, start-ups are investing in the field. Lixoft, the brainchild of Marc Lavielle and Jérôme Kalifa, was founded in 2011. The company sells software to help design clinical trials and may also enter the medical device market with a tool to identify patients most likely to respond to a particular treatment, using their biological data. “We’re still considering this option,” Lixoft CEO Jonathan Chauvin says. “But there are a lot of regulatory constraints.” Another aspect that must be taken into account.