Connected migrants : how digital technology is becoming a priority

- Since the 1990s and 2000s, digital technologies have transformed the lives of people on the move and the study of migration phenomena – a concept of the ‘connected migrant’ is emerging.

- Migrants can now contact their families from afar and can be reached every day, anywhere in the world.

- However, technologies are both a blessing and a curse for migrants: they combat loneliness, but also allow families to control them remotely, etc.

- Digital migration studies aim to provide a better understanding of migration practices, beyond preconceived ideas such as those about money transfers by people on the move.

- Today, the emergence of new technologies such as generative artificial intelligence raises new questions in the field of migration.

Before the advent of new information and communication technologies (ICT), moving abroad meant cutting off from a person’s roots and distancing from family, without always succeeding in integrating into the host country. But the arrival of mobile phones, the Internet, apps and online services in the 1990s and 2000s has significantly transformed the lives of mobile people and the study of migration phenomena. “With the advent of digital technologies, I wanted to show that a new type of migrant was emerging – that of the connected migrant,” explains Dana Diminescu, sociologist, lecturer and researcher at Télécom Paris (IP Paris) and director of DiasporaLab.

Emergence of digital migration studies

With the emergence of digital tools, migrants have become connected to technology. Using WhatsApp, Snapchat, Instagram or TikTok, they can stay in touch with their families, who may be located more than 10,000 km away1. Telephones, digital services and social networks mean they can be reached every day, anywhere in the world. Migrants carry their “home” in their pocket, in their flat or even when out walking in the city.

To demonstrate the emergence of the “connected migrant”, Dana Diminescu laid the foundations for a new approach to the study of migration with her DiasporaLab programme. “This involves the study of migration in relation to ICT, but it is also a sub-field of digital sociology2. A migrant equipped with digital tools leaves traces. In 2003, I wrote an epistemological manifesto on digital migration studies, which I have been studying for some twenty years.” The programme involves finding digital traces of different aspects of migrants’ lives, while combining them with a more traditional methodology. To do this, the researcher decided to use semi-automatic algorithms. After the data collected by the algorithm has been gathered, the researchers review it themselves to analyse it more thoroughly. “This choice was time-consuming, but it allowed us to obtain a much more controlled final corpus.”

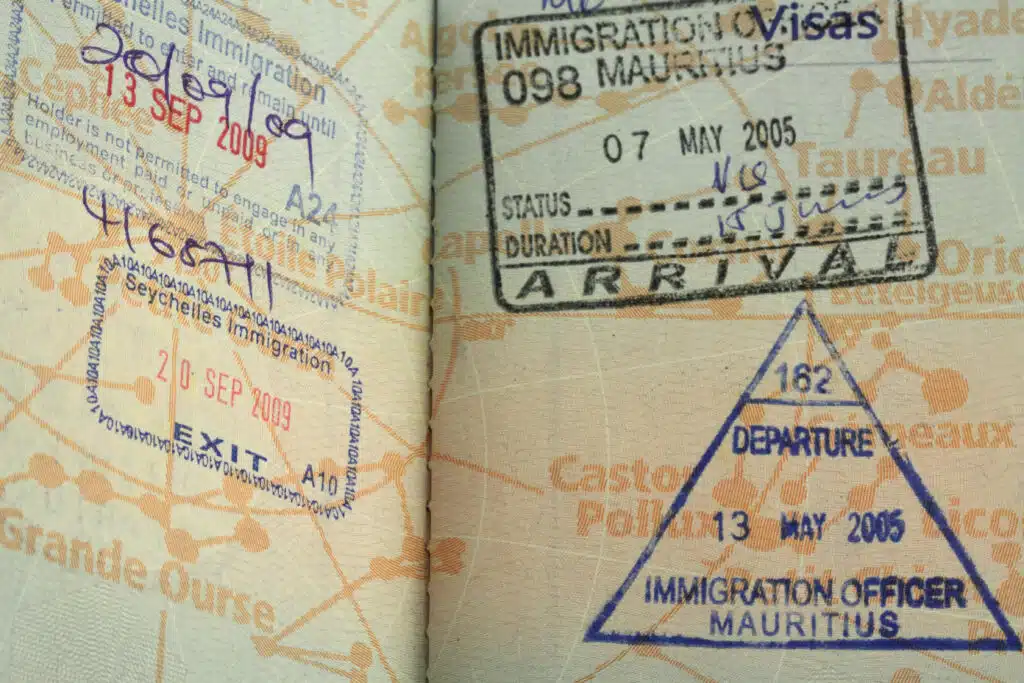

Connected migrants use new technologies to navigate between different environments : from the country of emigration to the country of immigration, and the journey between the two. Access to digital services, a bank card and a biometric passport facilitate their belonging to different worlds : civil institutions, family networks, professional networks, friendship networks3 and so on. “The Internet has been an excellent tool for diasporas, making it easier for migrants to come together, but the network has also created community bubbles,” she explains. “Sometimes migrants seek to break free from their family circle, but telecommunications become a form of remote control for the family.”

Overturning common myths

Digital migration studies also seek to better understand the habits and practices of certain migrant groups, beyond common misconceptions. “Migrants are proficient in communication tools. If there is a divide, it lies in navigating administrative platforms. Furthermore, one of their priorities when travelling to another country is to buy a phone. They often have several, which are both vital tools and aids to integration.” As the researcher points out, “what is interesting about digital sociology is that we don’t work on what people say, but on what they do.” This idea is well illustrated by a study co-authored by the researcher and published in 20104.

The work undermines the preconception that most migrants transfer money primarily to their families, and shows instead that they most often want to retain control over their financial transfers. “When we examine migrants’ data in detail, we see that they primarily send money to themselves. When we dig deeper through qualitative interviews, they explain that they send money to themselves to maintain a form of presence in their country, but also to participate in activities from a distance, without giving others power over their money.”

There is a gap in the research, namely the failure to take into account the emotions of the hosts.

In 2015, the Singa association created Calm, a platform for connecting refugees with individuals willing to welcome them into their homes5. Research based on this platform has shed light on expressions of hospitality online and the role of digital tools in welcoming migrants. However, Dana Diminescu stresses the importance of remaining attentive to the emotions of those who welcome migrants, which are often overshadowed by the abundance of data collected. “I was very moved working on the data from the SINGA platform, which I saw come into being and evolve. We collected 20,000 messages and registrations from French people who wanted to offer shelter or a home to refugees.” This study therefore revealed a shortcoming, namely the failure to take into account the emotions of those providing shelter in the research. “The French people said why they wanted to host, and each had a story, sometimes a really moving one. It can be a shame to bury emotion under too much digital technology.”

In this regard, the researcher co-signed with artist Filipê Vilas-Boas an artistic work installed at the National Museum of Immigration History since June 2023 and created by Mickaël Bouhier6. When visitors hold out their hands in front of the artwork, one of the 12,000 messages of hospitality from French people explaining why they wanted to host refugees via the CALM platform is displayed in the palms of their hands.

What next ? Monitoring AI

In conclusion, digital technology is transforming migration. It offers opportunities for communication and mutual support but also makes people more vulnerable to control and tracking. The rise of AI in our society also raises new questions. As the researcher points out, it spreads a lot of fake news and reinforces community bubbles. More broadly, the researcher is studying the influence of social media on immigrants’ return to their countries. “They sometimes develop a utopian narrative of return, a little nostalgic, a little heroic, anti-migration project of their parents.” However, “we do not yet know what AI will bring in terms of know-how and practices in general,” she adds. In any case, one thing is certain : migration is now inseparable from digital technology.