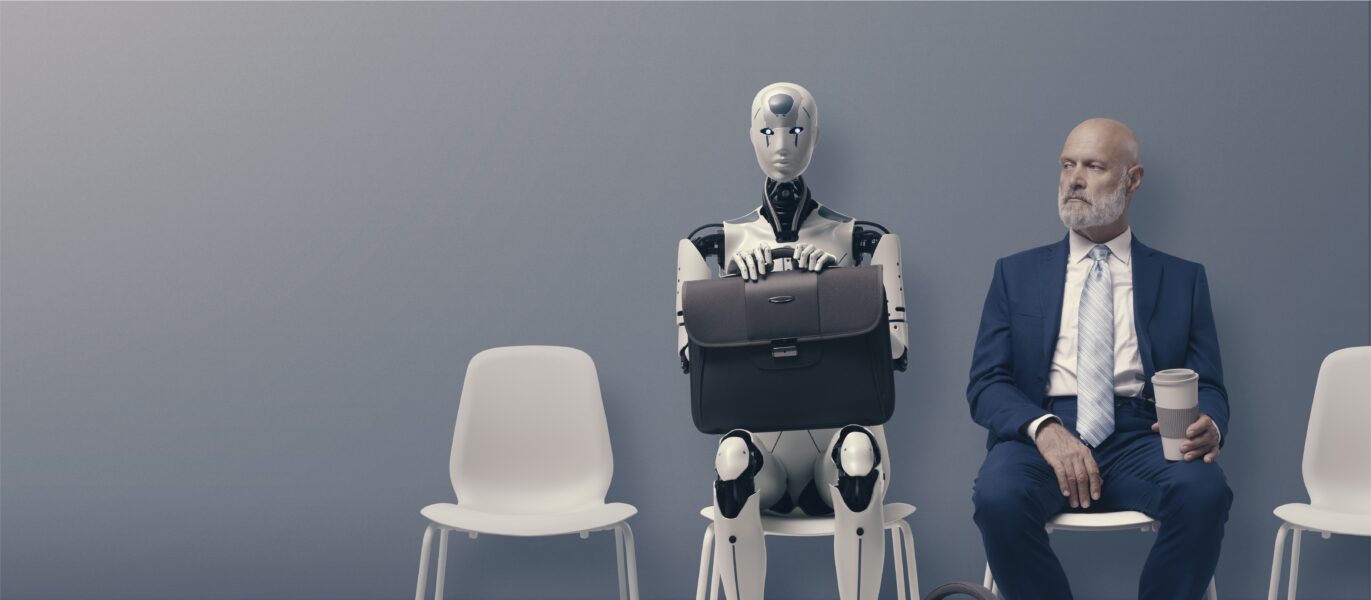

Computer systems are increasingly involved in everyday decisions, especially artificial intelligence (AI), which can take over functions previously performed by humans. But how can we trust them if we do not know how they work? And what about when this system is called upon to make decisions that could put our lives at stake?

Regulating AI

Véronique Steyer, lecturer in the Management of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (MIE) department at École Polytechnique (IP Paris), has been working on the question of the explicability of AI for several years. According to her, it is important to distinguish the notion of interpretability – which consists of understanding how an algorithm works, to improve its robustness and diagnose its flaws – from the notion of accountability. This raises the question: in the event of material or physical damage caused by an artificial intelligence, what is the degree of responsibility of the person or company that designed or uses this AI?

However, when they exist, AI explainability tools are generally developed with an interpretability logic, and not with an accountability logic. To put it plainly, they allow us to observe what is happening in the system, without necessarily trying to understand what is going on, and which decisions are taken according to which criteria. They can thus be good indicators of the degree of performance of the AI, without assuring the user of the relevance of the decisions taken.

For her, it is therefore necessary to provide a regulatory framework for these AIs. In France, the public health code already stipulates that “the designers of an algorithmic treatment […] ensure that its operation is explicable for users” (law n° 2021–1017 of 2nd August 2021). With this text, the legislator was aiming more specifically at AIs used to diagnose certain diseases, including cancers. But it is still necessary to train users – in this case health professionals – not only in AI, but also in the functioning and interpretation of AI explanation tools… How else will we know if the diagnosis is made according to the right criteria?

At the European level, a draft regulation is underway in 2023, which should lead to the classification of AIs according to different levels of risk, and to require a certification that would guarantee various degrees of explainability. But who should develop these tools, and how can we prevent the GAFAs from controlling them? “We are far from having answered all these thorny questions, and many companies that develop AI are still unaware of the notion of explicability, » notes Véronique Steyer.

Freeing up time-consuming tasks

Meanwhile, increasingly powerful AIs are being developed in more and more diverse sectors of activity. An entrepreneur in AI, Milie Taing founded the start-up Lili.ai in 2016 on the Polytechnique campus. She first spent eight years as a project manager, specialising in cost control, at SNC Lavalin, the Canadian leader in large projects. It was there that she had to trace the history of several major construction projects that had fallen far behind schedule.

To document complaints, it was necessary to dig through up to 18 years of very heterogeneous data (email exchanges, attachments, meeting minutes, etc.) and to identify when the errors explaining the delay in these projects had occurred. But it is impossible for humans to analyse data scattered over thousands of mailboxes and decades. In large construction projects, this documentation chaos can lead to very heavy penalties, and sometimes even bankruptcy. Milie Taing therefore had the idea of teaming up with data scientists and developers to develop an artificial intelligence software whose role is to carry out documentary archaeology.

“To explore the past of a project, our algorithms open all the documents related to that project one by one. Then they extract all the sentences and keywords and automatically tag them with hashtags, a bit like Twitter,” explains Milie Taing. These hashtags ultimately make it possible to conduct literature searches efficiently. To avoid problems in the case of an ongoing project, we have modelled a hundred or so recurring problems that could lead to a complaint and possible penalties.

Lili.ai’s software is already used by major accounts such as the Société du Grand Paris, EDF and Orano (nuclear power plant management). And according to Milie Taing, it does not threaten the jobs of project managers. “In this case, AI assists in the management of problems, which makes it possible to identify malfunctions before it’s too late,” she says. It aims to free humans from time-consuming and repetitive tasks, allowing them to concentrate on higher value-added work.

AI aims to free humans from time-consuming tasks, allowing them to concentrate on higher value-added work.

But doesn’t this AI risk point out the responsibility, or even the guilt, of certain people in the failure of a project? “In fact, employees are attached to their projects and are prepared to give away their e‑mails to recover the costs and margin that would have been lost if the work was delayed. Although, legally, staff e‑mails belong to the company, we have included very sophisticated filtering functions in our software that give employees control over what they do or do not accept to export in the Lili solution,” she states.

France ahead of the game

According to Milie Taing, it is in France’s interest to invest in this type of AI, as it has some of the best international expertise in the execution of very large projects, and therefore has access to colossal amounts of data. On the other hand, it will be less efficient than the Asians, for example, in other applications, such as facial recognition, which moreover goes against a certain French ethic.

“All technology carries a script, with what it does or does not allow us to do, the role it gives to humans, and the values it carries,” Véronique Steyer points out. “For example, in the 1950s, in California, a road leading to a beach was built, and to prevent the beach from being invaded by a population of too modest origin, the bridges spanning the road were set very low, which prevented buses from passing. So, I think it’s very important to understand not only how a system works, but also what societal choices are embedded in an AI system in a totally tacit way that we don’t see.”

Currently, the most widespread AIs are chatbots, which cannot be said to threaten the human species. But by becoming accustomed to the performance of these chatbots, we could tomorrow neglect to question the mechanisms and objectives of more sophisticated AI.