Artificial intelligence (AI) now occupies a central position in economic, political and managerial discourse. It is presented as a driver of social transformation, an unprecedented lever for productivity and a tool for creativity. However, beyond the technological enthusiasm, the economics of AI remain fraught with profound uncertainty because, despite the massive investments that demonstrate the confidence of public and private actors in its potential, observed impacts on growth and productivity remain unclear – sometimes even disappointing.

This tension between promise and reality raises questions about the conditions for value creation in AI-based digital ecosystems. Far from being a universal technology, AI is deployed according to different sectoral, institutional and territorial logics. Forms of AI integration vary based on to the availability of data, the skills of the players and organisational strategies. As developments in IT have already shown in the past, productivity gains depend not only on algorithmic performance, but also on the transformation of routines, complementary skills and coordination mechanisms.

Between universal promise and fragmented reality

Since the spectacular spread of so-called ‘generative’ models — those that produce text, images, sound or code — AI seems to have become a digital Swiss Army knife, capable of doing everything: writing a report, generating an image, composing music, designing a marketing plan or even writing code. With its ‘all-in-one’ nature, AI appears to be both a universal tool and a lever for automation and widespread creativity.

However, AI platforms do not just provide technical tools: they now structure markets, standards and behaviours, thereby contributing to a redefinition of power relations in the global digital economy. We are witnessing the rise of global players who, through the vertical integration of infrastructure, software and uses, are organising technological lock-in mechanisms that accentuate the asymmetries of dependency between countries, companies and users, while raising the question of digital sovereignty.

Behind the large multimodal models – which are supposed to be capable of doing everything – lies an AI economy that is increasingly segmented, contextual and targeted towards these usages. We are witnessing growing tension between two dynamics. On the one hand, there is a trend towards integration, embodied by large generalist models that seek to build global artificial intelligence platforms capable of responding to all types of needs. On the other, there is a trend towards specialisation, driven by start-ups, laboratories and sector-specific players (health, finance, industry, law, energy, culture, etc.), that are developing specialised, contextual models integrated into specific sectors and value chains.

Universal assistant or invisible functional building block?

In one case, AI is presented as a universal personal assistant, an intelligent interface for everyone. But in the other case, it becomes a functional building block, often invisible, integrated into business processes, analysis tools or production infrastructures.

The two approaches intersect and sometimes contradict each other. Large AI models are heavy, costly infrastructures that require enormous computing and data resources; their operation is based on economic principles similar to those of cloud platforms or integrated software ecosystems. Conversely, specialised models tend towards a more refined, often more ethical and sustainable use economy, but one that is fragmented and dependent on technical standards and interfaces or APIs opened up by the major players.

The illusion of a promise of universal or general AI is based on two important factors. The first is the fascination with generalist models. The ‘big models’ that make up ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Llama and Mistral are presented as universal platforms thanks to their versatility and multimodality, as well as the ‘all-in-one’ image they project.

AI giants and their strategies

The dominant players in AI — mainly large American and Chinese companies — are characterised by a vertical integration strategy: they simultaneously control the infrastructure layers (cloud, processors, networks), the application layers (AI tools, interfaces) and end uses. This model of ‘systemic platformisation’ allows them to capture not only the value generated by innovation, but also the externalities produced by interactions between users, developers and data producers. These companies operate as ecosystem architects, setting the rules for data access and sharing, interoperability standards and economic conditions for participation.

However, AI is also marked by two phenomena already encountered with IT and digital technology. The first is the Solow paradox: AI is everywhere – except in productivity statistics. Any gains only involve very specific segments and are quickly absorbed by investments and the deployment of new services and activities. AI only generates sustainable gains if it is accompanied by a reconfiguration of work and production, upskilling and collective learning. However, it takes time between acquiring technologies and being able to use them effectively.

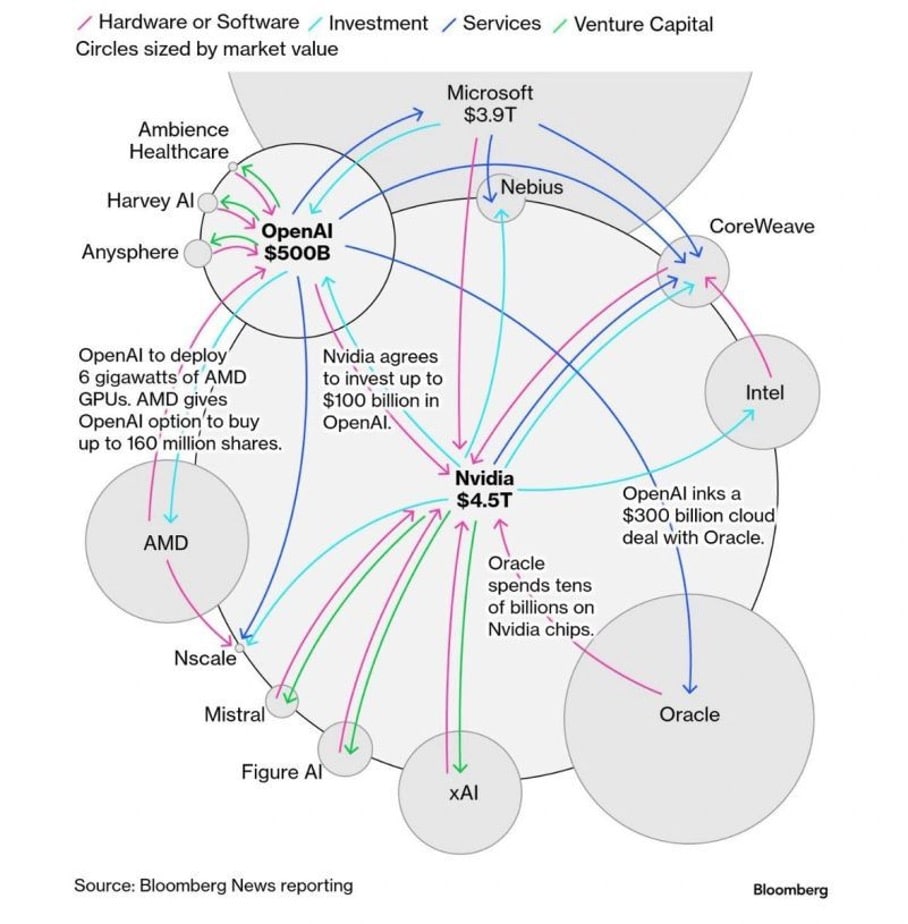

A second phenomenon is a bubble effect. On the one hand, it stems from massive investments across the board: Open AI is planning to invest $10 trillion by 2033, while announcing only $13 billion in annualised revenue this year and no profitability until 2030. The scale of these investments is also due to financial manoeuvres that go round in circles with endogamous agreements (see Figure 1) and a limited number of players and companies involved in AI, feeding off each other.

Faced with the risk of the bubble bursting, major digital players are turning their attention to the corporate world. B2B financial models are healthier because they do not require investment in computing power for inference. The enterprise markets and the digitisation of industry are proving to be a more important issue for the economy than the mass market and individuals, which are more often discussed.

The challenge of integration: beyond technology

Furthermore, the development of AI in businesses faces the more general difficulties of digitalisation of the companies themselves. Technologies are organised and intertwined in ‘systems’ without it being possible to isolate them from one another. They combine ‘technical building blocks + organisational elements + procedural rules and implementation processes’ in a way that is absolutely inseparable from one another. In their practices, agents and work collectives simultaneously mobilise different building blocks without being able to identify the specific contributions of each technical component.

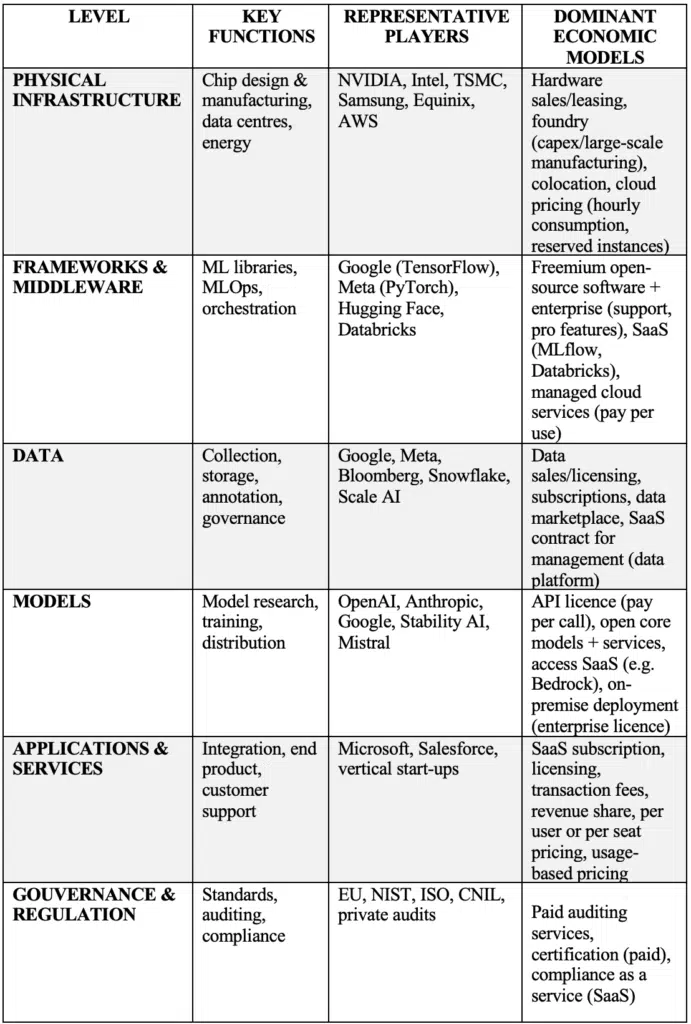

Value creation in the digital sector is based on specific combinations of technical resources and economic applications (see Figure 2). Several main interconnected links can be identified: the hardware that constitutes the physical infrastructure (components, infrastructure, equipment), the software that enables this infrastructure to be used (operating systems, interfaces, development tools), the data that represents the flow of information (collection, storage, processing), the models that structure the transformation of this data into knowledge or decisions (algorithms, machine learning, process representation), and finally the applications, which translate these capabilities into concrete economic and social uses (services, platforms, end uses), without even mentioning directives that establish the regulatory framework.

The highest value capture occurs at the level of models and their applications. High margins can be achieved through API licences, subscriptions and user lock-in. To a lesser extent, cloud and platforms also benefit from significant recurring revenues due to the lock-in they can achieve through their integration. Finally, semiconductor foundries and manufacturers (highly capital-intensive, high barriers to entry) and specialised data providers (local or niche monopolies) may capture only a small proportion of the value of AI, but their position remains the most strategic.

The diversity of business models

Generative AI models rely on the massive collection of heterogeneous data — often from open ecosystems — and its large-scale reuse. This process gives a major competitive advantage to players capable of accumulating and processing considerable volumes of information. However, the value derived from this data is not solely a function of its quantity, but also of its quality and contextualisation. The most effective models are those that manage to combine large scale with local relevance, integrating data specific to a particular use, sector or language.

Beyond concentration, the AI economy is also seeing a diversity of situations emerge. Infrastructure models are based on the provision of computing and storage capacity (cloud, GPU). This model, dominated by a few players, relies on economies of scale and network effects. Application models, on the other hand, focus on creating sector-specific solutions (health, finance, energy, education) tailored to specific needs. This model prioritises value in use and customer proximity. Finally, European public and industrial ecosystems favour consortium or partnership models in which companies cooperate to develop contextualised AI solutions, pooling data and risks.

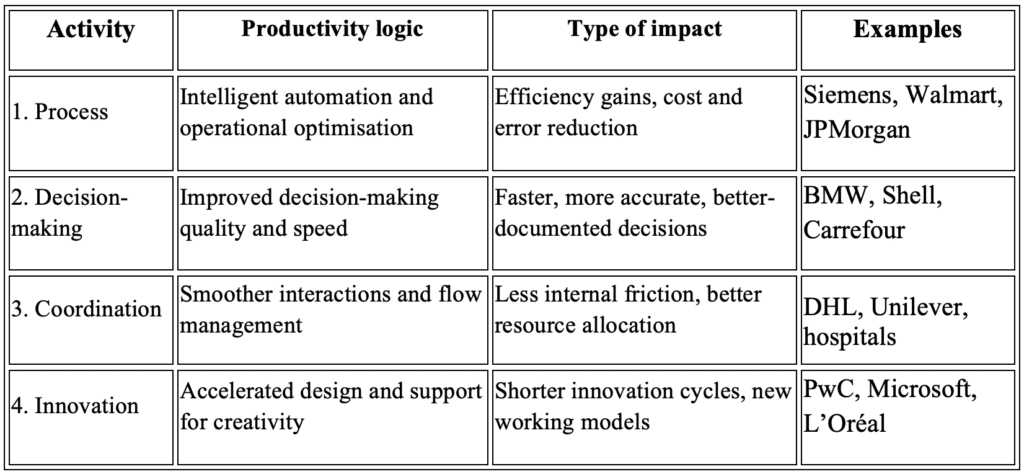

These trajectories confirm that value does not lie in the technology itself, but in the ability to orchestrate an ecosystem of heterogeneous players around an architecture. AI thus becomes an instrument of strategic structuring, rather than a simple production tool: it redefines relationships of dependency, sources of legitimacy and levers of competitive differentiation. More specifically, we can distinguish between uses of AI that relate to production processes, decision-making processes, cooperation mechanisms, or support for innovation (see Figure 3).

Thus, although public discourse on artificial intelligence (AI) often focuses on disruption and the replacement of human labour, its most tangible effect in most contemporary businesses is incremental improvements in productivity. In practice, AI acts as a lever for streamlining processes, accelerating decision-making, improving coordination and enhancing innovation capabilities. These transformations do not necessarily disrupt the structure of the company, but they do profoundly reconfigure its internal efficiency and value creation. This can be seen in the variety of existing use cases, which reflect the rise of vertical and sector-specific AI in healthcare, finance, law, industry, defence, energy, culture, and more. This variety is due to the specialisation of models and their adaptation to data sets and business constraints.