Trump 2: European military dependencies in question

- The defence policy of EU Member States is a matter of national sovereignty; institutions such as the European Commission are primarily political regulators and coordinators.

- A minority of EU Member States have a significant DITB (Defence industrial and technological base), while the vast majority do not and depend on non-European partners (the United States).

- Since Brexit, France is the only EU Member State to possess a nuclear arsenal and a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.

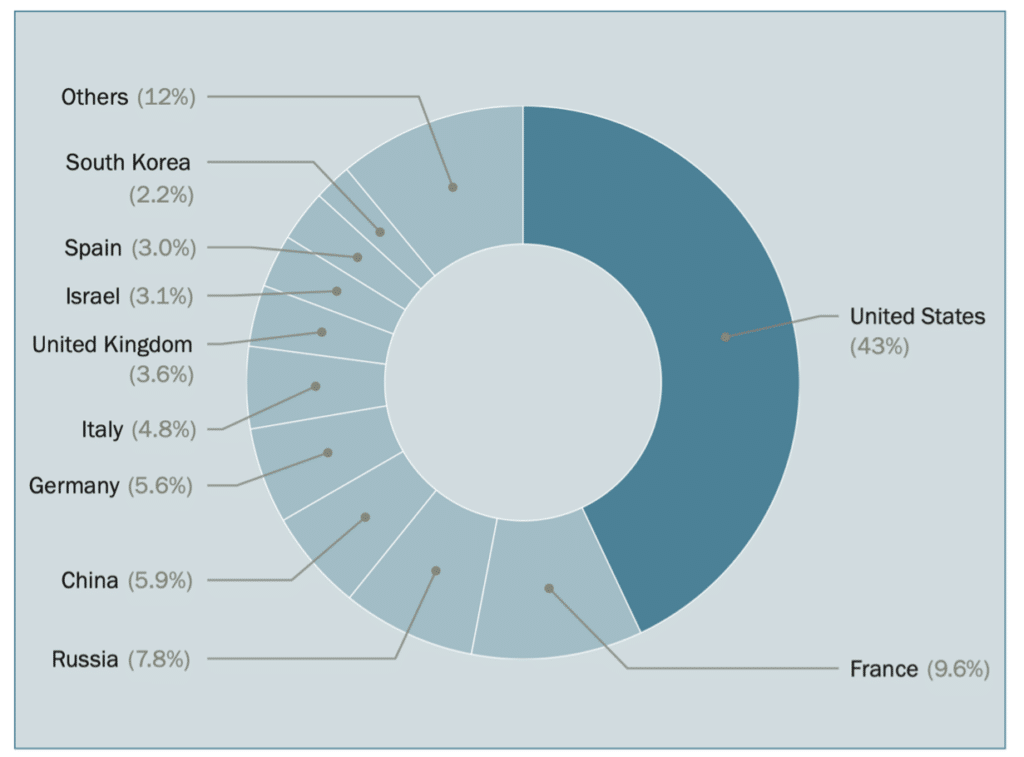

- The major European states are arms exporters, and in 2024 France alone accounted for 9.6% of global arms exports.

- In the face of the US disengagement from the defence of Europe, the ReArm Europe action plan seeks, for example, to strengthen the military capabilities of EU members.

In terms of defence and military equipment, who do the European states depend on?

Samuel B. H. Faure. Defence policy, like foreign policy or fiscal policy, is a matter of national sovereignty. Within the European Union (EU), this sector of public action is governed according to the so-called intergovernmental method, which places the twenty-seven Member States, including France, at the heart of the decision-making process through a preponderant role of the European Council and the Council of Ministers. In this way, supranational institutions such as the European Commission find themselves on the margins of European decision-making. The Member States retain their control over the acquisition of military equipment such as tanks, fighter planes and frigates, with the European Commission confined to a regulatory and political coordination role. The war in Ukraine, which broke out in February 2022, has not changed this political state of affairs. The Member States intend to retain their prerogatives and are de facto opposed to transfers of sovereignty. To understand the military-industrial dependencies of European political actors with the United States, one must shift one’s gaze from the European Commission in Brussels to the national level of the Member States.

A minority of them have a strong and autonomous defence industrial and technological base (DITB), while the vast majority of Member States lack one, which has created a significant dependence on non-European partners. For example, the Baltic States, namely Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – which share borders with Russia – but also Poland and Germany, have developed a close industrial relationship, particularly with the United States, to ensure the supply of capabilities to their armies.

When a country imports sophisticated military equipment, such as a fighter plane, it is not only buying the technology to meet an operational need, but it also expects to benefit from the security of this partner, especially when it is a nuclear power like the United States. Because of their geographical proximity to Russia and their perception of an existential threat to the integrity of their national territory, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe have sought, even more than the Western European states, to benefit from the American umbrella by acquiring American-made military technology. The most emblematic example is that of the American F‑35 fighter jet produced by Lockheed Martin, an American company that dominates the defence industry with a turnover of $60bn in 2023.

Many European states such as Germany, Finland, the Netherlands and Italy chose to acquire this aircraft, not only because of its technological excellence, but also and above all because it enabled these states to secure a “privileged” political and diplomatic relationship with the United States. As long as the White House remained this stable and solid politico-military ally, integrating F‑35s into their arsenal was not seen as problematic, but on the contrary as a profitable politico-industrial relationship: acquiring advanced technology, not having to pay the development costs of such weaponry or the industrial risks of such an undertaking, and having the political and diplomatic support of the world’s leading military power.

Is France a special case?

Due to its strategic culture resulting from the development of nuclear power in the 1950s and 1960s, France is one of the few European countries to benefit from a strong and autonomous DTIB. Since Brexit, France has been the only EU Member State to possess a nuclear arsenal and a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, which makes it, if not a “major power”, at least a “regional power” and a European military-industrial leader. Through its large companies, such as Thales, Dassault Aviation, Nexter, and Naval Group, as well as through the “European champions” Airbus and MBDA and its own growing military budget (€50bn in 2025, or 2% of its GDP), France’s military-industrial dependencies on non-European players, including the United States, have been and are relatively limited. The strategic military equipment imported by France from the United States since the beginning of the 21st Century can be counted on one hand. In 2013, Jean-Yves Le Drian, then Minister of Defence, decided to buy the “off the shelf” Reaper drone produced by General Atomics. In the context of the French armed forces’ engagement in the Sahel against jihadist terrorist groups, these drones met an urgent strategic need at a time when there was no French industrial supply.

If we reverse the perspective, are foreign armies dependent on equipment produced on European soil?

The major European states are arms exporters. According to the key SIPRI report Trends in International Arms Transfers 2024, more than a quarter of the world’s arms exports come from five European states: France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and Spain. In 2024, France alone accounted for 9.6% of global arms exports, ranking second in the world behind the United States (43%) and ahead of Russia (7.8%) and China (5.9%).

These export “successes” have been reinforced in recent years but are not new and are multifactorial. The expertise of French military-industrial engineering through the Corps of Armament Engineers and its engineering schools, such as Ecole Polytechnique (IP Paris), is recognised worldwide in all the industrial branches that make up the defence sector: nuclear, aeronautics and space, land, naval and the missile sector.

Furthermore, the fact that France has a “field army”, i.e. armed forces with the capacity to fight on the battlefield, legitimises the French and European weapons available to French officers. In 2024, France’s three main “clients” were India, Qatar and Greece, which are both business opportunities and political and diplomatic partners located in strategic areas: the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Southern Europe.

Faced with the disengagement of the United States in the defence of Europe, how can we rethink the military-industrial dependence on this long-standing ally?

For many European politicians, Donald Trump’s return to the White House on 20th January 2025 came as a shock. The President of the United States is calling into question the European security architecture that has been institutionalised around transatlantic relations since the end of the Second World War. Multilateralism, the rule of law, liberal democracy – all principles that have been championed by the United States in the establishment of the world’s liberal international order – are now under threat.

Until a few months ago, it was unimaginable that one of the President of the Unites States’ closest “collaborators” – in this case Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX and a key figure in the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) – would instigate foreign interference, contrary to international law, as he did during the German legislative elections in February 2025 by calling for a vote for the far-right AfD party, led by Alice Weidel. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the Americans launched the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe. In 2025, we find ourselves with the tables turned, with the second Trump administration threatening its closest allies: Germany, but also the United Kingdom, Denmark and Canada. This is a staggering development for all European politicians, and even more so for those who had built the collective defence of their national territory through, on and thanks to the “American umbrella”.

The first election of Donald Trump in 2016 was interpreted by many politicians and experts as a deviation or even “road rage” on the part of a majority of American citizens who were “discontent” with the Democratic establishment. His re-election, moreover, by a landslide in 2024, leads to the opposite conclusion, that this political movement, which could be described as “illiberal”, is a structural political trend of the 21st century, from Bolsonaro’s Brazil to Orban’s Hungary and Modi’s India. The effects of such a “policy” are major for the United States and Americans, but also for the world, and primarily for the collective security of the European continent in the context of the war in Ukraine. For the months and years to come, the most likely scenario on which European politicians must operate is that the United States will accelerate its political and military disengagement from the European continent. This situation is all the more worrying as European states currently lack the military and industrial capacity to defend themselves against a nuclear power such as Russia.

Many are dependent on the US administration to use military equipment imported from the United States. For example, the US authorities have the capacity to prevent the take-off of F‑35 fighter planes acquired by the Netherlands, Denmark, Italy and Germany, among others. If the US administration confirms its political distancing from its European allies, then military-industrial dependencies on the United States will be a “double whammy” for many European states: not only will they no longer be able to rely on the “American umbrella”, but they will also have to rearm quickly.

But are the European states prepared to take on their “strategic responsibilities”?

This, I believe, is the most thorny question for the months and years to come. Although a “strategic awakening” is taking place, there is still a long way to go and many political obstacles to overcome before proactive political discourse can be transformed into public policy instruments that are adapted to the seriousness of the geo-economic issues at stake.

On Wednesday 19th March 2025, a series of proposals were presented in Brussels by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and her Commissioner for Defence Industry and Space, Andrius Kubilius. The ambition was clearly stated: to make Europe a power that is “ready” when it comes to defence by 2030. To achieve this, a White Paper for the future of European defence and an action plan entitled “ReArm Europe” have been published, corresponding to a political roadmap and a “toolbox” to achieve it.

This plan for the rearmament of Europe has an overall budget of 800 billion euros over a period of four years to strengthen the military capabilities of EU Member States and accelerate technological innovation and industrial productivity. While these proposals are a step in the right direction, the main political risk – as counterintuitive as it may seem – is that European states will rearm against Europe and to the detriment of European strategic autonomy. This work of inter-state political coordination is the priority if Europe is to emerge from this unprecedented political crisis from a position of strength, i.e. by building a European power. Time is running out.