Splinternet: how geopolitics is fracturing cyberspace

- Today, cyberspace has become a battleground for power struggles between nations, leading to a fracturing of the global network.

- It can be used as a weapon of war between countries, to cut off access to information, retrieve data or spread propaganda.

- Some states are disconnecting from the global Internet in favour of their own network, isolated from the rest, over which they have control.

- Authoritarian regimes use this phenomenon to gain control over their population and public opinion.

- This weakens democracies: as the global Internet remains accessible to authoritarian regimes, foreign interference can occur.

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee and his team at CERN introduced an innovation that would change the world: the World Wide Web. This innovation, known simply as the Web, linked the entire world through almost international communication. This was its primary goal1: to enable researchers in different fields to communicate with each other and share their knowledge instantly.

The Splinternet is the establishment of a multipolar Internet, fragmented into as many closed cyberspaces as there are competing blocks in the world.

The Internet therefore comes from a dream, that of exchange, communication, and mutual aid. But today, this dream seems increasingly unrealistic. Why is this? According to Asma Mhalla, a specialist in the political and geopolitical stakes of the digital economy and a lecturer at Sciences Po Paris and École Polytechnique (IP Paris), cyberspace has undergone a process of militarisation, “It has become a battleground for power struggles between nations, and more precisely between distinct ideological blocs, leading to a fractured global network,” she says. “As such, the Splinternet was formed.”

What is the Splinternet?

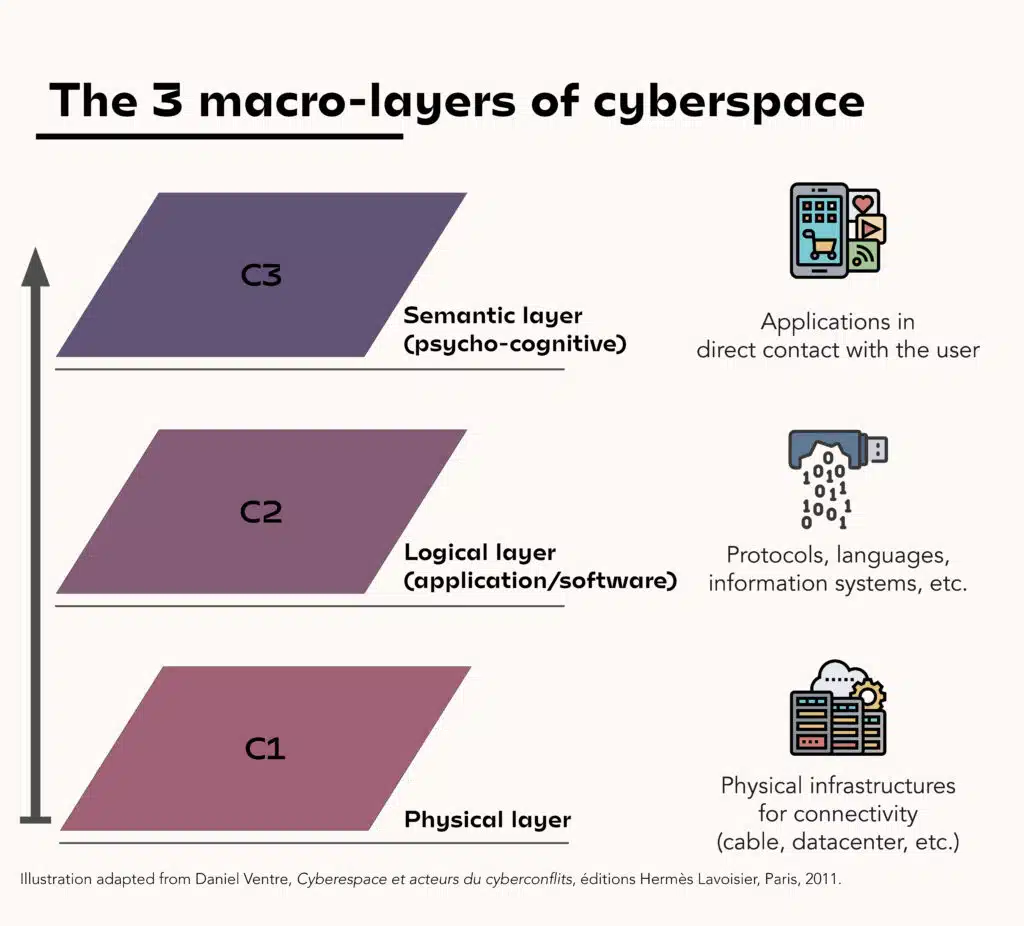

To better understand what the Splinternet is, it is necessary to understand what cyberspace is. This space is structured in three interdependent macro-layers2. The first is the physical layer, and revolves around the various infrastructures that enable this network of connectivity to be established: the datacentres, the servers, the cables, etc. The second is the logical layer: protocols, languages, information systems. And the last, the semantic or cognitive layer, refers to all the applications in direct contact with the user.

“Initially, this space was intended to be free and open. It was conceived in the 1960s with the ideas of its time and was then marked by the idea of happy globalisation,” explains Asma Mhalla. “However, the potential of this technology eventually turned it into a strategic issue. The Internet has thus become a new arena for influence, confrontation, and power relations between different world powers.” Today, its ubiquitous use and the wealth of data it generates make it a target of warfare – even a weapon. “This process of militarisation of cyberspace has made it the 5th dimension of conventional warfare (the first 4 being: land, sea, sky and space),” she says. “The three macro-layers have become targets for the military strategies of states.”

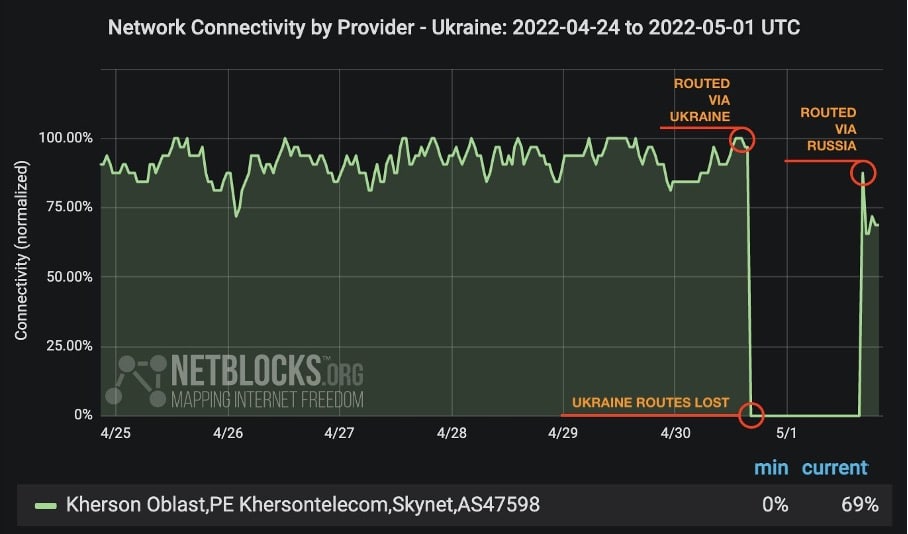

Take the example of the war in Ukraine: Russia is attacking the infrastructure (physical layer) to cut off the Internet, or at least disrupt it. The Netblocks association also accuses Russia of having redirected the Ukrainian network to its own network, with the aim of recovering data (logical layer). Finally, the Kremlin’s influence on applications in direct contact with the user (semantic layer) allows it to spread its propaganda and justify its invasion.

“Through this process of militarisation, some states, such as Russia, are beginning to disconnect from the global Internet,” she notes, “in favour of an isolated and disconnected Internet, a kind of scaled-up intranet. Basically, and beyond the question of technical feasibility, the subject is nothing less than ideological: the Splinternet is the establishment of a multipolar Internet, fragmented into as many closed or semi-closed cyberspaces as there are competing blocks in the world. This phenomenon is taking place in symmetry with the recomposition of the world order currently being pushed by states such as Russia and China, which are working towards a multipolar international order that will disrupt American predominance.”

An existing fragmentation

According to this definition, it is clear that the Splinternet is already here. And China was the first to launch this fragmentation. It started with the implementation of the Great Firewall of China, aimed at blocking access to all websites that do not support the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). While not censoring the entire Internet, the Chinese government has managed to establish pervasive control over its content. “This shield, which limits access to American technology giants, particularly for uses that interface directly with users, has created a relatively closed ecosystem,” says Asma Mhalla. “The aim was to quickly create a sovereign Chinese tech ecosystem, and more specifically the BATX, the Chinese digital giants, enabling the CCP to develop a form of technological sovereignty under control, essentially social and political control.” Today, the CCP has been able to develop a Chinese Internet, with its 3 macro layers, and its own worldview.

However, China is not the only power to have embarked on a project of this scale. Iran, too, has developed its own structures to have an Internet cut off from the world. And recently, Russia seems to be moving in the same direction, as Kévin Limonier, a Russian-speaking cyberspace specialist, notes. The Russian network was connected to the global Internet, but, according to Limonier, Putin is gradually developing the idea of informational sovereignty4. This can be seen in various pieces of legislation issued by the Kremlin over the past decade. The law “On the creation of a sovereign Internet”5, adopted in November 2019, is the most significant with regard to the Splinternet. This 100% Russian internet has been named the RuNet.

China is not the only power to have embarked on a project of this scale.

In Russia, as in China, the Internet was initially connected to the global network, and it remains difficult to disconnect from it. “Russia is still in a test and learn phase for the first two layers of cyberspace,” says the specialist. “As for the third layer, the semantic layer, it is gradually disassociating itself from it. RuNet will accelerate the process.” The Russians are beginning to have their own network of applications in direct contact with the user: search engines, social networks, e‑mail systems, etc.

With these three Internets, developed by these different powers, we can consider that the global Internet, ours, is a fourth part of the Splinternet – albeit not a closed one.

Democracies in a weak position

The Splinternet is therefore already present, and the countries that have provoked this state of fragmentation have one thing in common: they are authoritarian regimes. This commonality seems logical: the Internet has the characteristic of facilitating debate and the exchange of opinions, which can be seen as antagonistic to dictatorship. Moreover, the Internet offers the possibility of controlling the information that is disseminated on it, and therefore the possibility of informational sovereignty: authoritarian regimes have an interest in having this type of control, which is synonymous with the control of local common opinion.

However, circumvention strategies exist, such as the use of a VPN. Even if in a dictatorship these strategies remain isolated acts and are not mainstream, VPNs show that this fragmentation is not watertight. The concern is that the level of impenetrability is not the same between dictatorships and democracies, for the simple reason that the global Internet remains accessible to powers with their own Internet. The destabilisation of our Internet can therefore be massive, as foreign interference is easier to achieve.

“This is the great weakness of democracies in this story, because the networks remain porous by nature,” says Asma Mhalla. “This porosity represents an opportunity for interference and influence at low cost for authoritarian regimes. Democracy can, in the long run, be really weakened by this. The Western bloc is thus in an existential crisis and must quickly clarify its technopolitical model.” In April, in the midst of the war in Ukraine, Joe Biden called for a “free and open” Internet. This appeal, which was signed by some sixty countries6, shows the concern of Western countries, and their willingness to act, about the direction that cyberspace is taking. However, the future of the Internet also raises other questions for European countries, particularly concerning their dependence on the Americans in this area.