Population density: not a primary factor in Covid-19

From a demographic standpoint, what can we say about the Covid-19 crisis?

In my book Serons-nous submergés ?, which was published in October 2020, I studied the way the first wave of the pandemic unfolded, day after day, in four countries – France, Switzerland, Italy and Spain. I studied them at the level of regions, counties and provinces. The results showed that geographic – rather than social – factors were key for dynamics of the epidemic. Certainly, as many studies have shown, immigrants and low-income people have a higher risk of dying from Covid-19 than the rest of the population. Not because of where they’re from or how much they earn, however. Rather, it is because of their proximity to the virus. These populations work in hospitals, at supermarket checkouts, as delivery persons or taxi drivers. That is why they are more impacted. The virus cannot distinguish between an immigrant and a non-immigrant, nor can it tell how much money you make. Rather, it goes straight to the nearest person, and we can learn a lot more about who the nearest person will be through geography.

We often think of Covid-19 as an “urban virus”. However, your study found that population density was not one of the key factors in its spread. Why is that?

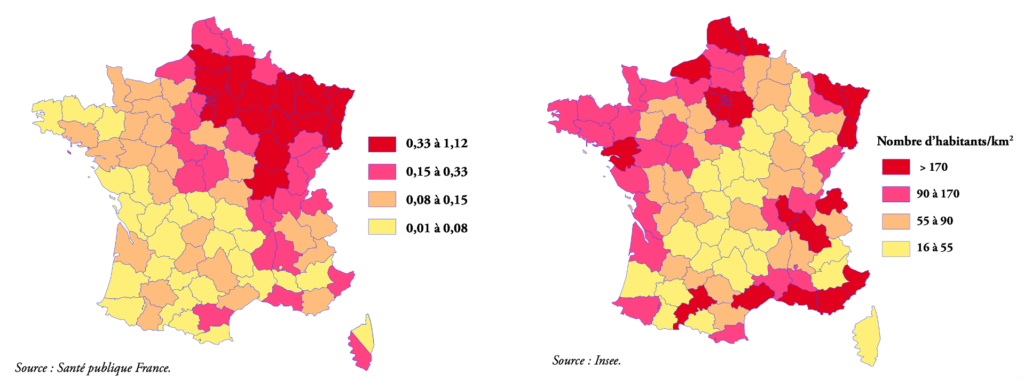

When you compare Coronavirus deaths between 1st March and 15th May 2020 with the density of French départements, there are huge differences. Over that period, the mortality rate in Territoire de Belfort (1.18 per 1000 residents) was 170 times higher than that of Ariège (.007 per 1,000). The contrast between a map of mortality rate and a map of population density shows no correlation (see below).

Density is not a factor in the large-scale spread of the virus. What matters is the location of clusters, which are initially linked to just one person. The more people are contaminated before the infected person realises, the harder it is to contain the epidemic. This is what happened with the second wave, but the differences in mortality remain considerably different – sometimes as much as tenfold higher. And we see that “patient zeros” appear in both the countryside and the city including large towns such as Mulhouse and Ajaccio, but also smaller ones like Auray, Creil or even a village in Savoie, Les Contamines-Montjoie.

Hence, while density matters as the epidemic spreads, the initial impact is minimal. The only thing that we can say is that patient zero is a traveller. So, they often appear near big international hubs (Geneva, Milan, Roissy Airport near Paris, New York, etc.). But they also travel out of the city, which is where the cluster develops, i.e. Crépy-en-Valois, La Bastide-Montjoie, Bergame. This is actually what happened at the start of the AIDS epidemic.

So to control the spread one must first control people’s movements – hence the lockdown. After exponential growth of cases in the first clusters (Mulhouse, Auray, Milan, etc.), the epidemic in the first wave was contained. For example, it practically didn’t get into the Loire at all, nor into Andalusia or Southern Italy. It also explains why deaths were thirty times higher in Milan than in Naples. It’s a reminder of how, during the last outbreak of the bubonic plague in France (Marseille, 1721), lines of soldiers were deployed to prevent the epidemic from spreading beyond the Provence region.

Let’s go back to social criteria. Which did you select for your study?

In each of the countries included in our study, figures for Covid-19 deaths were compared with four indicators: density, poverty, the proportion of immigrants in the population, and the proportion of people over 70 years old. The geographic distribution of these four factors gave us no indication of which segment of the population would be impacted. The maps speak volumes. This is due to the fact that the first wave was contained in the four countries studied.

What about the second wave?

Paradoxically, the second wave originated at the end of the first lockdown. The number of daily cases was very low at the end of June. But people in the 15–49 age bracket accounted for two thirds of new cases. Many of them passed by undetected, as they were asymptomatic. With people travelling for the summer holidays, the virus spread all over France. Older people, particularly grandparents, were also infected.

As such, in October France found itself with a large number of clusters. With the exception of Mayenne, these could not be contained as seen in Ajaccio, Auray and Les Contamines-Montjoie. As a result, the epidemic spread pretty much everywhere, as it had done in the two big clusters in the first wave in Creil and Mulhouse.

Because of more widespread safety measures and improved healthcare, the virus did not spread very quickly. The spread of Covid-19 across almost the entire country has produced new social differences connected to what happened during the first wave – certain groups are more careful than others, as shown by debates about mask-wearing. Nevertheless, regional differences are not insignificant – between coastal Brittany and the Lyon region, the rate of cases and the mortality rate varies by a factor of ten.

Just as we saw in the first wave, the second lockdown (preventing people from travelling) will probably maintain these differences, once the wave has been stopped. Like other contact epidemics throughout history, controlling people’s mobility remains an essential factor for controlling the epidemic. We had better remember that if we want to prevent a third wave.