How to improve the hospital system: a question of organisation?

- Hospitals can sometimes suffer from organisational complexity, where different logics – medical, administrative and care – cross paths, sometimes conflicting with one another.

- The book L’hôpital apprenant (The Learning Hospital) takes up the challenge of proposing coordination methods that take these different “hospital rationales” into account.

- Poor cooperation between different hospital stakeholders can, for example, lead to a “silo effect” and a lack of flexibility, which have a negative impact on the organisation.

- On the contrary, the efficient flow of information and issues between sectors enables problems to be resolved in the best possible way.

- The role of the hospital director is therefore to be on the ground to understand everyone’s circumstances and to act as an intermediary between the various hospital stakeholders.

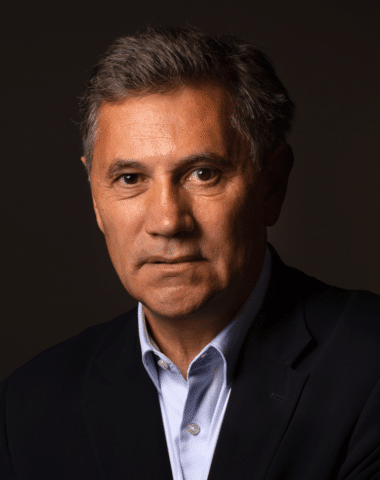

There are numerous problems surrounding the hospital system in France. The most visible in the media are the lack of resources, the crisis in recruitment and staff burnout, though the organisation of these institutions is rarely questioned. Yet, as places of advanced medical technology, hospitals can also suffer as a result. There are three different approaches at play – medical, administrative and care – which can be difficult to reconcile. This is the challenge that Guillaume Couillard, director of the Paris Psychiatry and Neuroscience Hospital Group, attempts to address in his book co-written with Anne-Lise Seltzer and Michael Ballé, L’hôpital apprenant — L’amélioration continue du service de soin1 (The Learning Hospital: Continuous Improvement in Healthcare), published in 2024.

“Often, public debate about how hospitals work focuses on questions of power — who should decide?” observes Guillaume Couillard. “In my view, however, the real issue is how the different rationales that coexist within a hospital can cooperate effectively and intelligently.” Of course, hospitals, like all large structures, have a bureaucracy — that is, rules defining roles and responsibilities, as well as procedures. The aim of this book is not to question them, because “they were born out of a necessity. If all organisations in the world have defined organisational rules, it is perhaps because we don’t know how to do otherwise, but also because it is generally very effective: it gives millions of people access to high-tech care. We must therefore be as aware of the value of this type of system as we are of its limitations.”

The real challenge is not to question these rules, but rather to ask ourselves how we can improve the way in which they work.

Reconciliation of conflicting rationales

A hospital brings together various actors who do not all do the same job, and each of them follow a specific process to accomplish their tasks. This is what the director of the Parisian hospital calls “hospital rationales”. “The first rationale is medical,” he explains. “Fundamentally, it is based on medical science – that is, on the state of the art standards and best practices established by science. Then comes the administrative rationale: this is essentially a set of rules and regulations that must be followed, which apply to organisations in addition to a resource allocation rationale. The care rationale, on the other hand, is found in the day-to-day organisation of services and remains quite distinct from the medical rationale.”

The first common failure made in large organisations is poor cooperation between the various players, causing a “silo effect” – due to a lack of communication, everyone does what they have to do within their own area of responsibility, which usually results in systemic effects being overlooked. In addition, “these three approaches are constantly interacting,” says Guillaume Couillard. “To get them to cooperate, information needs to flow freely. However, staff will always tend to assume that everyone else has the information they need to do their job.” This gives rise to a second effect, which the authors of the book also identify as a cause of failure: the “rigidity” — “everything will be fine if everyone does what they are supposed to do.” These two issues tend to perpetuate a vicious circle. “In reality, not only does good information circulate very poorly, but it is also very partial,” he insists. “We tend to look at it from our own point of view, not by ignoring the views of others, but by making assumptions about what the reality of others might be.”

Understanding each other’s circumstances

A clear example would be a broken radiator in a room. Since he GHU where Guillaume Couillard is director has multiple sites, the plumber’s travel time must be taken into account. “In this very simple case, the maintenance team will seek to optimise its resources,” he explains. “Before heading to a distant site, it might be better to wait until there is more than one radiator to repair.” In this case, the maintenance team is assuming that this is not a serious problem. Without ignoring the problem, they do not attach the same importance to it as the healthcare team. “For other hospital departments, a broken radiator means a room is out of use,” adds the director. “This can cause real difficulties in the operating schedule, for example. Although everyone is thinking rationally, the lack of communication between the two parties creates a real problem.”

“Good information flow also means understanding a situation from everyone’s perspective, for all parties involved,” concludes Guillaume Couillard. “You can’t understand it by assuming what it means for others.” So, when there’s a problem, however big or small, if information doesn’t flow properly, the problem will only get worse and, more importantly, won’t be resolved in the best possible way. “There is also a tendency to shift the blame onto others: let’s imagine that someone has not done what they were supposed to do. We would then say that “they did not follow the procedure”,” he explains. “In reality, the real question is rather why they did not follow it. Especially since, in most cases, anyone in the same situation would have done the same thing.”

This gives the role of hospital director entirely new significance. Above all, they must be actively involved, understand everyone’s circumstances and act as an intermediary between all the different hospital departments. According to Guillaume Couillard, this requires a great deal of self-awareness: “You must be comfortable with the fact that you don’t know everything! Some managers still struggle with this, but you always have to make an effort to get out into the field to fully understand the reality of the situation. We always think we know what’s going on. But in reality, we don’t know exactly, and we won’t know until we go and ask the people directly involved.”

It is therefore essential to set up regular meetings, with a certain degree of formality designed to bring out all aspects of the situation and communicate each of these rationales. Communication must also be effective. “The secret ingredient is simply to agree on our problems and not on what we think is a solution,” he insists. “This step is often overlooked. Initial discussions generally focus on solutions: “we need to do this”. This approach gets the problem-solving process off to a bad start, as it not only causes disagreement, with everyone contributing their own solution, but also reinforces the two effects mentioned above (silos and rigidity).” It is therefore a matter of organisation that must take everyone’s point of view into account, opening up new perspectives for thinking about the hospital of tomorrow…