The placenta: a legacy inherited from ancient viruses

- In the human genome, there are about 500,000 of these retroviral genomes, which represent about 8% of its total length – much more than the length of our own genes which are only 1-2%.

- These molecular companions are not new: the most recent one is about 150,000 years old, and they can be considered as viral fossils.

- In 2000, during a survey of the proteins expressed by various human tissues, researchers identified a viral protein produced in a single organ: the placenta.

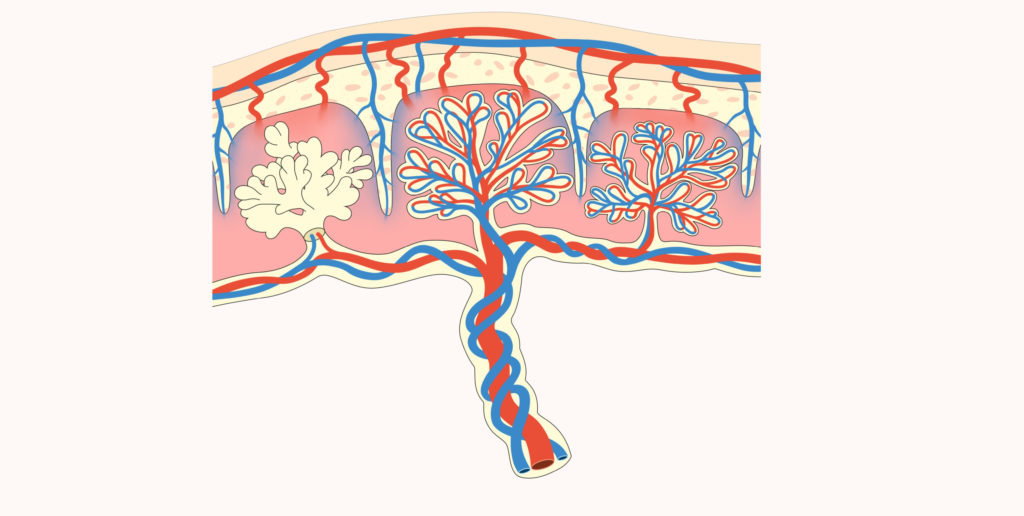

- This viral envelope protein is specifically expressed in a tissue of the placenta called syncytiotrophoblast, which allows exchanges between the mother's blood and that of the foetus.

- Observations of this type are multiplying, and it is becoming necessary to rethink our vision of viruses: they are not only vectors of disease, but also of genetic innovations.

Since their discovery at the end of the 19th Century, viruses have been associated with the notion of disease. And with good reason: it was in the search to understand the origin of some of them that these new kinds of infectious agents were identified. However, as explained in a previous column, viruses can become our allies in the fight against bacterial infections. But this is only a recent twist: long before any human mind had the idea of using these microscopic entities to our advantage, the vagaries of evolution had already united us in a particularly intimate way.

Viruses in our genome

While only 1–2% of the human genome consists of protein-coding sequences, between half and two thirds are made up of different types of multiple-repeated sequences, the functions of which are difficult to determine. And viruses have a lot to do with this.

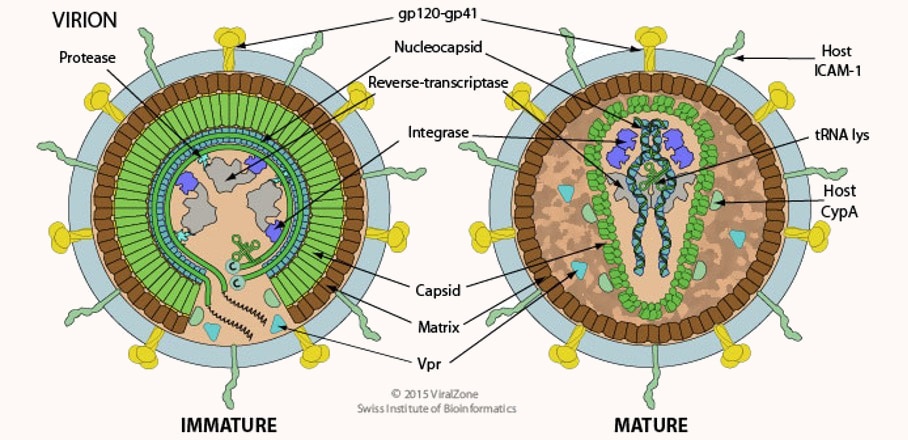

Those belonging to the retrovirus family, the best-known member of which is HIV, which causes AIDS, have a very special ability: they can integrate their own genome into that of the cells they infect. This insertion sometimes takes place in a germ cell that eventually produces gametes (spermatozoa or oocytes in humans, for example). In this case, the squatting viral genome is passed on to the next generation and is found in all the cells of these new individuals, who will in turn pass it on to their offspring. Thus, over time and through infection, retrovirus genomes have become well-established in the DNA of other species – including our own.

In the human genome, there are about 500,000 of these retroviral genomes, which represent about 8% of its total length… That’s much more than the length of our own genes (the 1–2% mentioned above)! And these molecular companions are not new: the most recent one is about 150,000 years old. So, they have had time to accumulate many random mutations and most of these viral genes are no longer expressed today. They can be considered as viral fossils, which are in fact among the objects of study of a discipline called palaeovirology1.

But as always in biology, there are exceptions. Some viral regulatory sequences still modulate the expression of our own genes, and some viral genes are still expressed in our cells. Is this a reason to panic? Not really. On the contrary. Because we owe our birth to them. Literally.

The viral origin of placenta

In 2000, during a survey of the proteins expressed by various human tissues, researchers identified a viral protein produced in a single organ: the placenta2. It is a retrovirus envelope protein, usually found on the surface of viral particles, which has two particularities. On the one hand, when exposed to host defences during infections, envelope proteins are able to decrease the efficiency of the immune response. On the other hand, it is these proteins that, like molecular keys looking for their locks, interact with receptors on the surface of cells and cause the virus envelope to fuse with the cell membrane.

This viral envelope protein is specifically expressed in a tissue of the placenta called syncytiotrophoblast, which allows exchanges between the mother’s blood and that of the foetus. This tissue, which is essential for the proper development of the pregnancy, is formed by the fusion of several cells and has immunosuppressive activity. This leads us to believe that the formation of the essential syncytiotrophoblast is due to the action of a viral envelope protein…

The viral envelopes specifically expressed in the placenta and capable of inducing the fusion of several cells (to form tissues called syncytia) take their name from this last property and are now called syncytins. In the plural, because the discoveries have been made one after the other since 2000.

And in other mammals…

Two human syncytins3 are now known, also present in other Primates4, and genes of the same type have been discovered in many Mammals: Rodents5, Leporidae6, Carnivores7, Ruminants8… And even Marsupials9, which have limited development in utero. And this list is neither exhaustive nor detailed. In fact, syncytins have been found every time we have looked for them in a viviparous species (whose embryos develop inside the mother’s body, as opposed to oviparous species, which lay eggs). This underlines the importance of these viral genes in placenta formation! In mice, their indispensable nature has even been directly demonstrated10.

The diversity of syncytins currently observed in mammals, which are descended from the same common ancestor, is probably explained by the progressive acquisition of new endogenous retroviruses in each of the different lineages. In a sort of evolutionary relay, the ancestral syncytin would have given way to a whole series of different syncytins11. Several studies have already identified ancient syncytins in some organisms and the link between syncytin diversity and variations in placenta morphology is an open research question.

This close link between viviparity and domestication of a viral protein could be due to one of the main difficulties of non-egg reproduction: the mother’s organism has to tolerate that of the foetus during the whole gestation period. If there is no specific adaptation, its presence should trigger rejection, as in the case of a transplant. Various mechanisms now combine to allow this feto-maternal tolerance but, at the time of the appearance of viviparity, it is possible that viral proteins of the syncytin type were indispensable because of their immunosuppressive capacities.

In the absence of being able to go back in time to demonstrate this, we can look at the few viviparous animals that do not belong to the mammalian group12. French researchers studying syncytins have identified one of them… in a South American viviparous lizard13! The role of these viral proteins in viviparous reproduction is therefore not limited to Mammals, and it remains to be seen whether their presence is really systematic in animals with a placenta.

The link between syncytins and viviparous reproduction is particularly well studied, but it is not the only example of function dependent on the domestication of a viral gene. Beyond the syncytiotrophoblast, initial results indicate that syncytins may play a role in the formation of other tissues that require the fusion of several cells, namely certain muscles14, certain structures responsible for the regression of bone tissue and certain giant cells involved in the regulation of inflammation15.

Another retrovirus protein is expressed in our brains, where it is notably involved in memory1617. Parasitoid wasps have domesticated whole viruses, which they inject into the arthropods they parasitise at the same time as their eggs, to promote their immune tolerance18. Conversely, various retrovirus genes protect the organisms that carry them from infection by other viruses19.

Observations of this type are multiplying, and it is becoming necessary to rethink our vision of viruses. In constant interaction with other biological entities, they are not only vectors of disease, but also of genetic innovations that have turned the evolution of life upside down20.