Migration: the effects of climate change

- In the summer of 2024, Indonesia is moving its capital from Jakarta to Nusantara for climate related reasons: it is sinking due to urbanisation and the pumping of groundwater.

- Climate change has direct and indirect effects on migration: destruction of property, reduced agricultural productivity, increased spread of disease, etc.

- Today, migratory flows are mainly made up of men of working age, but extreme climatic events will lead to the migration of entire families.

- It is difficult to separate the impact of climate change from other drivers of migration, as climate change interacts with social factors.

- Certain regions are vulnerable: the small islands of the Pacific are the most affected by rising sea levels and South-East Asia is threatened by flooding.

In the summer of 2024, the President of Indonesia inaugurated Nusantara, the country’s new capital. The country became the first to move its capital for climate-related reasons, among others: the old capital, Jakarta, is sinking1 due to urbanisation and the pumping of groundwater, and the impacts – particularly flooding – are worsening as sea levels rise. In France, the expropriation and subsequent destruction in 2023 of Le Signal, a residence in Soulac-sur-Mer threatened by the receding coastline, has left its mark on people’s minds. The climate – and its evolution – is pushing men and women to move around the planet. In 2023, more than 26 million internal displacements were recorded due to natural disasters, particularly floods and storms, according to the 2024 World Report on Internal Displacement.

What are the factors behind migration? Does climate feature in this list?

Katrin Millock. There are many factors that determine migration: economic, social, political, demographic and cultural. Weather conditions can affect each of these factors. For example, a hurricane can come as a shock to people, and lead to a drop in income, which in turn triggers migration.

Can you tell us more about how climate change is affecting migration?

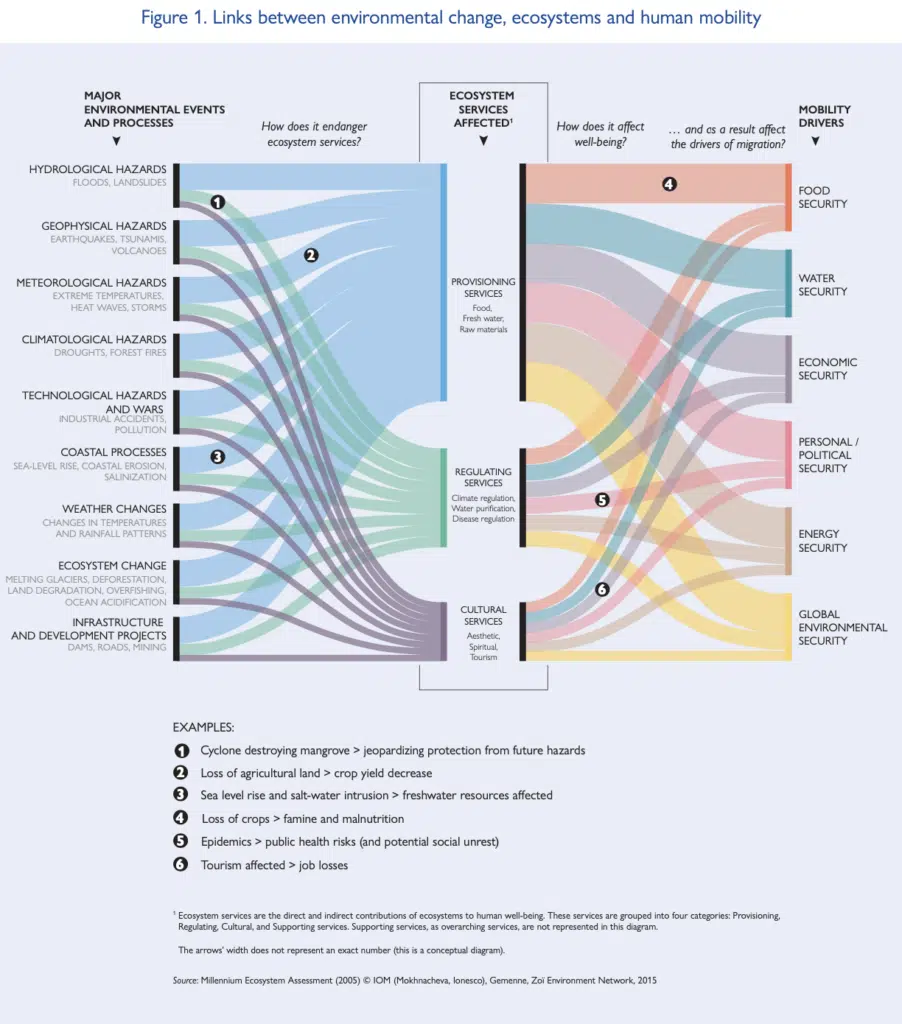

Climate change has both direct and indirect effects on migration. The most obvious direct effect is the destruction of property during extreme weather events, which often leads to temporary displacement. Another direct effect is the reduction in agricultural productivity because of drought: in countries where a large proportion of the population depends on agriculture for their livelihood, this leads to a reduction in income and therefore to migration. Finally, the direct effects of climate change – such as increased circulation of vector-borne diseases – can make certain regions uninhabitable.

One of the indirect effects recorded is the impact on the economy. It has been observed that those who migrate are not always the people directly affected. For example, the price of a crop affected by drought may rise and this increase in price may cause consumers to migrate.

Does climate change only affect the number of displaced people, or does it have other impacts on migration?

Climate change has several different impacts on migration. There is no single answer; it depends very much on the local context. We know, for example, that the composition of migratory flows will be affected in the future. While today we tend to see the movement of men of working age, extreme climatic events will lead to distress migration, i.e. when whole families move. Many studies also show that extreme events tend to be associated with temporary movements over short distances, often within the same country. Conversely, slow-onset phenomena such as desertification tend to create permanent migratory flows. In India2 and Africa3, various studies have shown that urbanisation is induced by rising temperatures, but only for cities with a transport network and employment opportunities in sectors other than agriculture. But as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) points out in its latest report4, there are still many uncertainties about the impact of climate change on migratory flows.

Why is this?

It is difficult to separate the impact of climate change from other migration factors. Climate change interacts with social factors: for example, studies show that political institutions are dependent in the long term on our environment and on climate change. However, they themselves influence migration processes.

The second obstacle is methodological. To isolate the impact of climate change, we need to ensure that other factors remain constant. However, climate change is a long-term process, during which the other factors will also evolve. To overcome this difficulty, most studies focus on extreme weather events, which are almost instantaneous processes. But these studies do not allow us to fully assess the effects of climate change.

There are also data problems: in climatology, the impact of climate change is considered to be visible over a period of at least 30 years, and often more. Yet socio-economic data often covers shorter periods. We don’t even have reference data from before climate change: the oldest complete data on international migration only dates back to 1960.

Do we have any idea of the future impact of climate change on migratory flows?

To my knowledge, only two studies provide robust results. In Science, two authors use asylum applications in the European Union to assess the impact of rising temperatures in southern countries5. They note that between 2000 and 2014, asylum applications increased when temperatures moved away from an optimum of around 20°C – the optimum temperature for agriculture. They estimate that claims could increase by 28% (i.e. around 100,000 extra claims per year) by 2100 for an average greenhouse gas emissions scenario (RCP 4.5). In 2022, in the Journal of the European Economic Association6, another team estimates the number of additional climate migrants (of working age) by the end of the century at 45, 62 or 97 million (depending on future greenhouse gas emission scenarios). Even if the projections are quantified, these results should be considered as orders of magnitude, given the uncertainties involved.

Are certain regions or populations more vulnerable?

That depends very much on how climate change manifests itself. The small islands of the Pacific, for example, are the hardest hit by rising sea levels. South-East Asia is mainly threatened by flooding, while population flows around the Mediterranean, West Africa and Asia will be affected by drought and extreme temperatures. Migration linked to falling agricultural productivity will tend to affect South and Central America and parts of Africa. Finally, the demographic factor is a major determinant of migratory flows, and it will be predominant in Africa in the future.

We also know that it is the wealthiest households that have the resources to migrate. The poorest households are trapped in place, and studies show that climate change will lead to increased inequality, poverty and mortality for those who do not have the opportunity to leave. It is crucial that international bodies take these immobile populations into consideration.

Interview by Anaïs Marechal

Find out more:

- Benonnier, T., K. Millock and V. Taraz. “Long-term Migration Trends and Rising Temperatures: The Role of Irrigation”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy 11(3), 307–330, 2022.

- Becerra-Valbuena, L. and K. Millock. “Gendered Migration Responses to Drought in Malawi”, Journal of Demographic Economics 87(3), 437–477, 2021.

- Cattaneo, C., M. Beine, C. Fröhlich, D. Kniveton, I. Martinez-Zarzoso, M. Mastrorillo, K. Millock, E. Piguet and B. Schraven. “Human Migration in the Era of Climate Change”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13(2), 189–206, 2019.