Institut Polytechnique de Paris (IP Paris) is in the process of creating a new Interdisciplinary Centre for the Study of Seas and Oceans (Centre Interdisciplinaire pour l’Etude des Mers et Océans, CIMO). This project is the result of the forthcoming merger of ENSTA Bretagne and ENSTA Paris, which gives the IP Paris an ocean campus in Brest and significant potential for marine and maritime education and research. Ocean observation is one of CIMO’s key areas of research. Given the climate and biodiversity crises and the sustainable development objectives, it is now of vital importance to observe the oceans.

The United Nations has launched the “Decade of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development” (2021–2030), led by UNESCO. And the United Nations is organising the 3rd United Nations Ocean’s Conference (UNOC), which will take place in Nice next year. As engineers, IP Paris scientists can bring a fresh perspective to research into the marine environment and maritime activities, and the CIMO will be a melting pot for this.

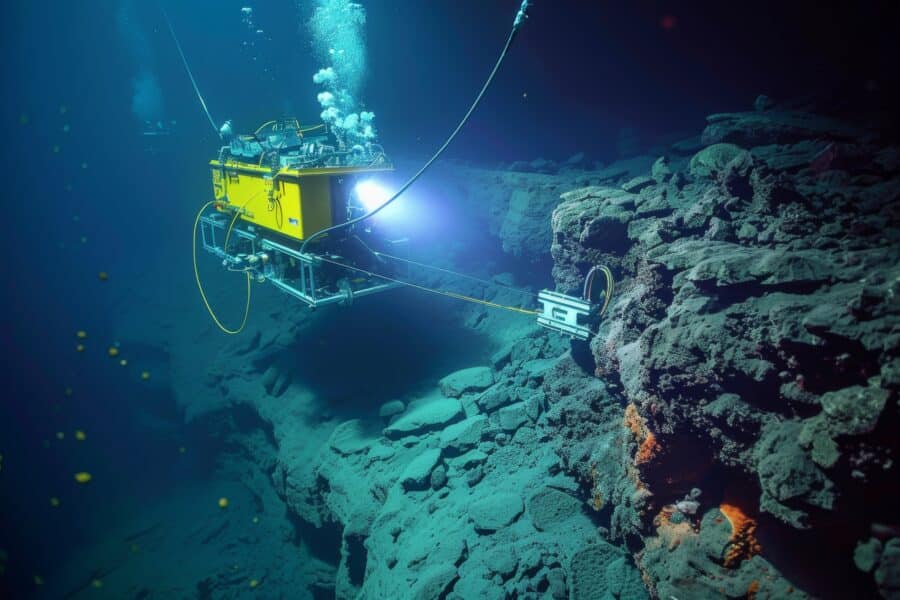

Ocean observation techniques have progressed considerably in recent decades. While observations have long been made from research, commercial or even pleasure and racing vessels, it was satellite observations in the 1970s that revolutionised many aspects of land and ocean observation. Today, in the age of robotics, surface observations by satellites can travel completely autonomously from the surface to the seabed. Autonomous systems, and gliders in particular, have revolutionised observation of the marine environment. They are inexpensive and can carry miniaturised scientific sensors to depths of nearly 6,000 metres. And they are sparking a host of innovations in many fields.

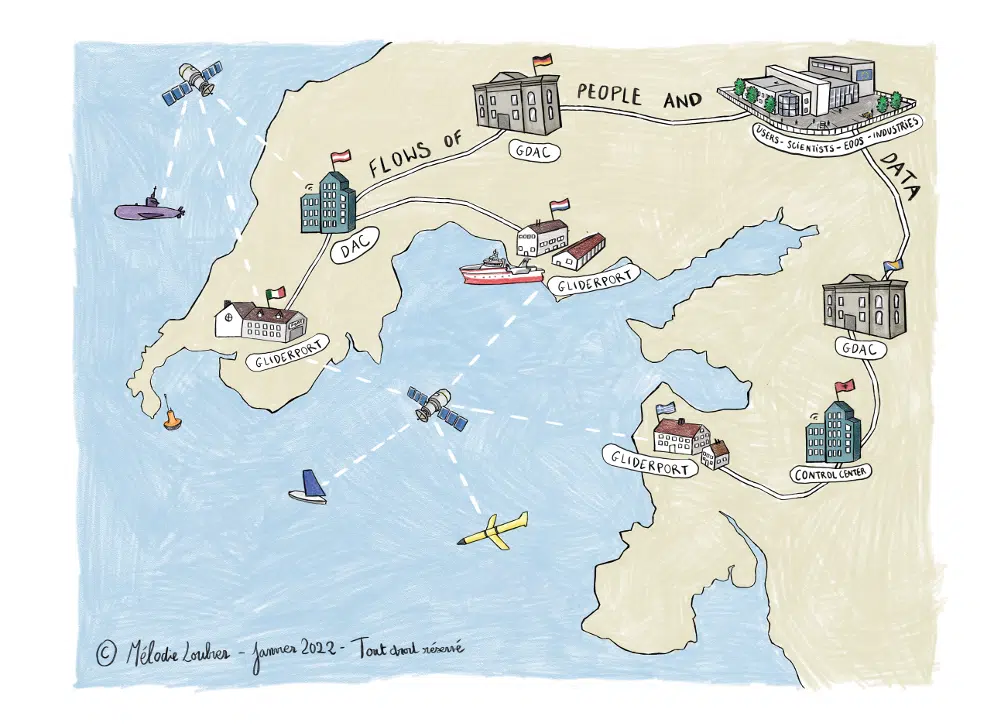

To make the most of these small robots, which are deployed in large numbers – there are currently 4,000 “Argo” profilers (the simplest of these robots) – specialised infrastructures are needed.

GROOM II and AMRIT, key projects to support ocean research

In Europe, there are a number of major Research Infrastructures (RIs) dedicated to different sciences or major societal issues, organised and largely funded at a European Union level. One of these, which everyone has heard of, is CERN [Editor’s note: European Organization for Nuclear Research]. Another is the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile, a collection of very large telescopes. In the context of ocean observation, the Horizon 2020 GROOM II project (Gliders for Research, Ocean Observation and Management Infrastructure and Innovation) is developing a coordinated European RI to support research and Ocean Observation Systems (OOSs) with autonomous systems capable of remaining autonomous in the ocean for months or even years.

Over the past 20 years, Laurent Mortier, from ENSTA Paris, has devoted his career to setting up these types of RIs and OOSs. He is currently coordinator of the Horizon Europe Advanced Marine Research Infrastructure Together (AMRIT) project, after having coordinated GROOM II, which has just come to an end. Europe is increasingly encouraging the integration of RIs and innovation, and in this respect autonomous marine systems and the GROOM II proposals will play a cornerstone role in the future edifice of marine RIs. In particular, AMRIT will develop standards, best practices and tools to ensure that observation data can be optimally integrated into existing and future climate prediction models, serving the needs of research and the wider blue economy and society.

“One of the aims of AMRIT is to improve the ocean component of the Copernicus programme [Editor’s note: an EU programme that collects and reports data on the state of the Earth on a continuous basis],” he explains. By observing the ocean, which influences the climate, models will be able to better predict ocean dynamics, as well as weather and climate. “This is obviously essential for understanding climate change, but above all for proposing mitigation and adaptation measures,” adds Laurent Mortier. Today, ocean forecasting and information services are mainly provided by the Copernicus Marine Service, managed by Mercator Ocean International in Toulouse. This entity was largely created by polytechnicians from the French Navy’s Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service.

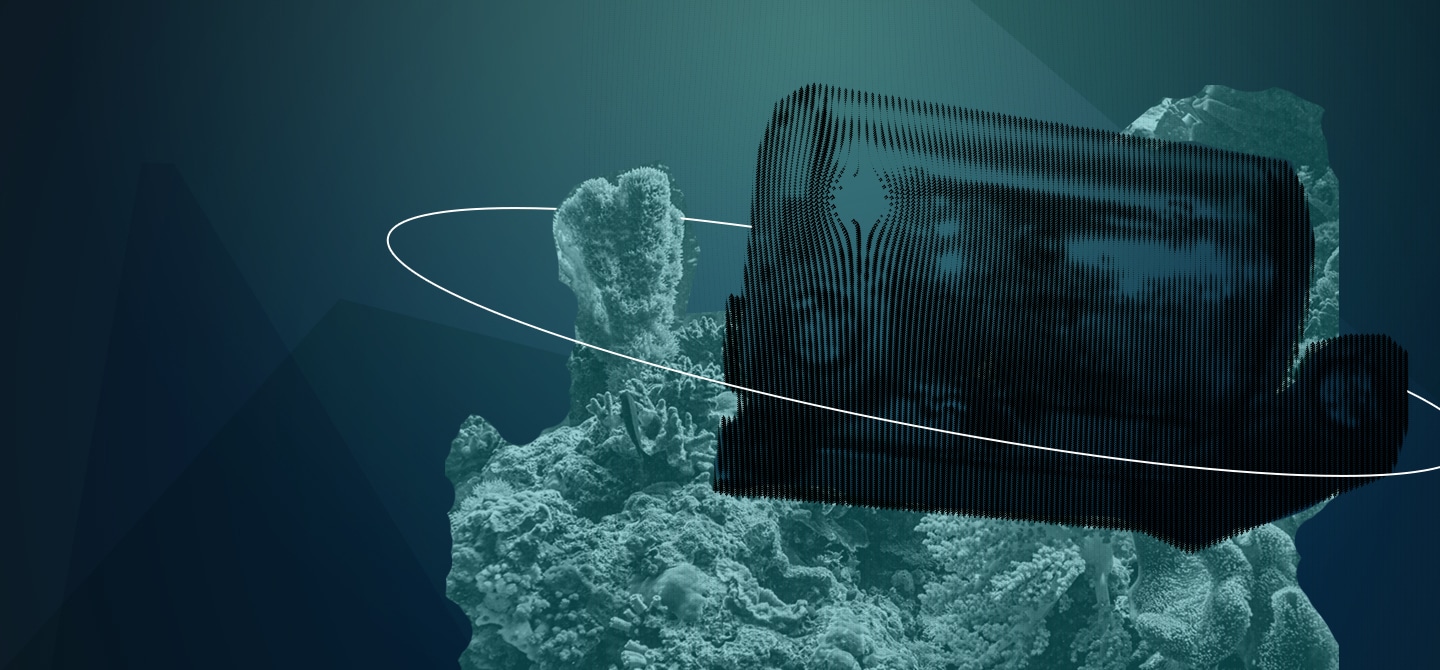

The importance of a digital twin of the Ocean

To this end, researchers have already turned to artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. Destination Earth, a major project of the European Commission and the European Space Agency, is developing a digital twin of the Earth, with its ocean branch EDITO. These digital twins are based on advanced models of the Earth system, which are then used to integrate more applicative digital twins. But to function, these models and digital twins need a regular flow of observations and data, covering all physical and living elements, for example in extreme environments, at great depths or under the Arctic ice. “It’s an almost impossible task, unless you go in with autonomous underwater systems,” explains Laurent Mortier. “Robotics is one solution, but it’s not easy to send robots under the ice and the instruments they carry can get lost. These twins will prove useful in designing the observation systems of the 21st Century.”

“France has often been a pioneer, and AI has been very useful in improving the design of the SWOT satellite mission to map ocean currents from space at high resolution” he adds. IP Paris could position itself in this field, as it has a number of laboratories capable of taking on this type of work on much more complex problems involving a large number of parameters.

GOOS and EOOS, systems to be financed and supported

“In addition to Argo, the revolutionary observation programme launched in the 1990s, which is the cornerstone of the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), we now need to integrate all the observation systems to ensure that these digital twins are really useful,” explains Laurent Mortier. “And GOOS wouldn’t really exist without funding from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Europe doesn’t have the equivalent of NOAA for the oceans. Agencies such as Ifremer, research bodies and universities are trying hard to coordinate the European component of GOOS, the European Ocean Observing System (EOOS), but neither the Commission nor the Member States have yet found a way to make it work and, above all, to fund it. The European Commission contacted me recently because it sees AMRIT as a project that could change all that.”

He adds that a new regulation proposed by the Commission entitled “Ocean Observation – Sharing Responsibility” could be a decisive step forward. If adopted by the next Commission, it will oblige EU Member States to observe the oceans in an operational way. “Observation of the oceans includes many elements: temperature, salinity, of course carbon, but also fish and parameters more related to maritime activities, such as noise – and of course pollution. Carbon is the parameter that we all want to try and measure much more systematically, because the ocean is a carbon pump, and this pump is being dangerously weakened by climate change. Better monitoring of the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon is now essential, and it’s a global issue.” The Global Green House Gases Watch (G3W), an ongoing programme of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), is working in this direction, and measuring carbon dioxide exchanges could become compulsory.

“This will be the focus of my work over the coming months. With my colleagues from the European marine RIs, we have every intention of influencing EOOS and proposing solutions. And with its exceptional research potential, IP Paris must be part of this collective effort” says Laurent Mortier.

Interview by Isabelle Dumé

Reference:

OceanGliders: A Component of the Integrated GOOS DOI:10.3389/fmars.2019.00422