In addition to the environmental insecurity caused by the climate crisis and the energy insecurity caused by the war in Ukraine, there is a looming mineral insecurity that could impede Europe’s energy and digital transitions. Cobalt, copper, lithium, nickel, rare earths, and other critical minerals are essential for all low-carbon technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, batteries for electric vehicles or hydrogen fuel cells. Hence, according to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA)1, consumption of these metals is expected to rise sharply by 2040. The metals are now vital to all economic sectors, and are central to government concerns, driven by the global push to decarbonize, systemic rivalries between powers and a growing awareness of the planet’s limits2. In this context, marine mineral deposits are drawing the attention of various states and companies. According to Article 76 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, coastal states have sovereign rights over resources within 200 miles of their shores. Beyond this limit, this is “the Area” where the sea and seabed belong to no-one despite the abundance of resources.

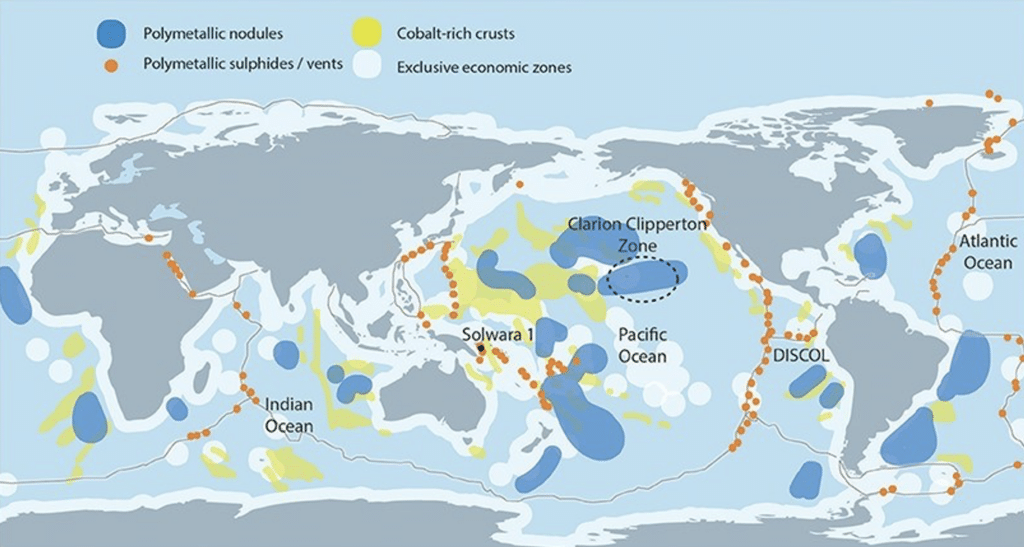

These deposits come in three forms: sulphide clusters, cobalt crusts and polymetallic nodules. Polymetallic nodules are small pebbles lying on the seabed which are particularly sought after for their high nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese content. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is an area of particular interest due to its high concentration of nodules; the zone is in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and covers approximately 4.5 million km² (the size of the European Union (EU)) (Figure 1). With the International Seabed Authority (ISA) due to meet on 15 July3, it is timely to examine the issue of seabed mining.

Underwater exploration campaigns are currently underway, but no commercial extraction is on the agenda. Deep-sea mining faces a several major obstacles:

- It is technically difficult and costly (1 to 5 million dollars for the extraction vehicles alone), not to mention the high and uncertain costs of operating and restoring the abyss;

- It could have significant ecological impacts, including loss of biodiversity, major disruption of ecosystems and pollution, which are difficult to measure at present;

- Most of the mining potential lies beyond the limits of national jurisdictions, in what the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea5 (UNCLOS) calls “the Area”, and states are struggling to agree on a unified regulatory framework.

The Area is administered by the International Seabed Authority (ISA)6, a UN entity defined by UNCLOS and created by the 1994 Agreement. ISA has the exclusive mandate to organize and control activities in the Area for the benefit of mankind. It is therefore up to ISA to set a framework for the exploration and exploitation of deep-sea mineral resources. Since 2014, the organisation has been leading negotiations to develop an international mining code. However, the task has proven difficult: while the Republic of Nauru has been pushing the UN body since 2021, and ISA Council and General Assembly are scheduled to meet this summer, they have already announced that finalising such a regulation would not be possible before 20257. The drafting of this mining code thus marks a renewal of inter-state relations and brings forth a new geopolitical field, with its own issues, institutions and fault lines.

The seabed at the crossroads of traditional geopolitics

The issues surrounding the exploitation of deep-sea mining resources are at the crossroads of several traditional geopolitical fields:

- High Seas Geopolitics: The area is the focus of discussions about freedom of navigation, definition of exclusive economic zones, the sharing of fishery resources, and strategic defence, surveillance and intervention positions. The high seas are a battleground for the strategic interests8 of states, particularly coastal ones, as they try to delineate the perimeter of this “Area” of uncertainty. Underwater resources are seen as a new front for asserting sovereignty.

- Mining Geopolitics: Most major mining countries have a clear-cut opinion on deep-sea mining. Proponents argue that it reduces the environmental impact of land-based extraction and prevents future supply disruptions. Competition from these mineral resources is taken seriously by the traditional mining countries. Some try to limit the scope by advocating a moratorium, as Chile does, or attempt to become mining superpowers, like China. Similarly, potential deposits are already included in the supply security policies of countries, as Japan.

- Climate Geopolitics: Ocean has recently gained prominence as a distinct subject, dealt with in dedicated arenas9 and at the core of ambitious texts such as the recently adopted High Seas Treaty10. Through this lens, underwater resources face the same tension as climate negotiations in general: preserving a key ecosystem while enabling all countries to develop.

- Commons Geopolitics: Designated as a “common heritage of mankind”, the deep seabed faces the same issues of equitable sharing as other res nullius. A parallel can be drawn with Antarctica, which was protected from exploitation by the Antarctic Treaty System in 1959. Supporters of a deep-sea mining ban advocate for a similar position, while other states assert their right to appropriation.

Negotiations on a possible deep-sea mining code thus involve these various analytical perspectives and give rise to a new geopolitical sphere with its own players, negotiating dynamics and timetable. ISA11 is the central player in this sphere, responsible for both regulating the mining industry and protecting the seabed. Strategies for influencing deep-sea mining are developed within its orbit. ISA comprises 167 Member States – and the European Union (EU) – each with varying degrees of influence within the organisation. Not all contribute to the organisation’s budget, 34 States have a permanent mission to ISA, 21 hold exploration contracts in the Area, 36 serve on the ISA Council and 41 have an expert on the Legal and Technical Commission.

Actors in tension between exploitation and protection of deep-sea resources

ISA is established as an omnipotent entity, tasked both with missions to protect marine environments, and to regulate activities within the Area and ensure equitable sharing of financial and economic benefits among states12. These conflicting missions make the ISA’s position delicate and sometimes at odds with other UN structures. For instance, UNEP13 warns about the uncertainties and potential environmental, social and economic risks of deep-sea mining14 when ISA is tasked with drafting a mining code to regulate its practice.

ISA is criticised for its lack of impartiality between its missions. For example, its funding model means that the organisation can’t stop granting licences without threatening its own continuation. Receiving $500,000 for each exploration licence issued, as well as an annual fee of $47,000 per contractor, ISA relies heavily on income from the licences it grants15 for its own funding. Its functioning makes it more likely to act as a regulator rather than a protector. Its operational mode also favours its regulatory mission over its protective one. The organisation is criticised for its lack of transparency and its insufficient consideration of scientific advice. Particularly concerning are the “two-year rule”16 activated by Nauru in 2021 and China’s veto17 on placing a discussion on the agenda for banning the granting of exploitation licences until regulations are adopted, raising fears of potentially silencing opposition to deep-sea mining within the ISA.

In ten years of negotiations on the mining code, the dividing line has shifted. Originally centre around methods of regulating deep-water mining, the debate now questions the very desirability of mining these resources. There are two distinct sides: on the one hand, countries such as China and Nauru which are in favour of speeding up the approval process (fast track), and on the other, countries such as Canada and Peru that are in favour of a 10 to 15-year moratorium, Brazil and Ireland which support a “precautionary pause”, and France which asks for a ban.

The movement advocating a moratorium on deep-sea mining is relatively recent and growing rapidly. It began with the creation of the Alliance of Countries Calling for a Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium on the initiative of Fiji, Palau and Samoa in 2022. It now includes 27 countries and continuous to gain momentum. Several countries are actively engaged on this issue and want to position themselves as spearheads in the preservation of the deep seabed. For instance, France recently signed an agreement with Greece18 joining it to the movement. France aims to use its role as co-organiser (with Costa Rica) of the United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice in June 2025 as the culmination of the “Year of the Sea”. However, the media coverage of the moratorium support movement should not overshadow the fact that most countries have not defined a clear position on the issue and that discussions on the subject are evolving rapidly.

Drilling in the Area: a new geopolitical fault line

Deepwater mining represents a new divide within traditional alliances, whether economic (G7, BRICS+, EU), geographical (CELAC, African Union, AOSIS) or strategic (OPEC, MSP etc.). This makes international relations more complex, forcing states to form new and more ad hoc coalitions to defend their positions.

States mobilise four types of narratives, which clash in the media sphere to justify or reject seabed mining19. The first two emphasize the potential benefits of mining: a) access to metals needed for the ecological transition by reducing environmental pressures on land, and b) profits created in the Zone that would be distributed among developing countries, becoming a tool for redistributive justice. On the other hand, the next two narratives emphasize c) our lack of understanding of the seabed and the ecosystem services it provides to the planet, and d) the need for a strict protection policy, favouring metal recycling over a new extractive front. As these arguments clash, three divide lines can be observed within allied blocs that illustrate these new tensions: among small island states, among Western countries and within what is considered the Global South.

The first group, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), made up of 44 states threatened by climate change, succeeded in having 1.5°C adopted as a warming target under the slogan “1.5 to survive”, thanks to their coalition at international negotiations. However, they are now divided on the issue of deep-sea mining, between the economic potential of the resources and the risks to marine biodiversity. Some, like Nauru and Tonga, want to exploit marine resources to finance their development. By threatening to trigger the two-year rule, Nauru is even seeking to press for the adoption of a marine mining code by ISA. Others, such as Vanuatu, Palau and Fiji, support a moratorium or even a total ban on mining. Vanuatu and other islands in the “Melanesian Spearhead” group20 adopted a memorandum21 in August 2023 rejecting mining activities in their waters and calling for protection of the seabed, signalling the gap with their former partners.

In the West, there is a sharp division between those in favour of exploiting the seabed (United States, Norway, Japan, South Korea, etc.) and those advocating a pause or even a total ban (Germany, Canada, Finland, France, etc.). The former stress the strategic importance of access to metals for the energy transition and national security, while the latter point to scientific uncertainty about the environmental impact. The United States, which is neither a signatory to the UNCLOS nor a member of ISA, can hardly influence the development of marine mining rules, which is why a bipartisan resolution in November 2023 supports ratification of the treaty22 in the name of securing supplies of critical metals, particularly from China. On the other hand, Canada and France are defending a moratorium and a total ban on seabed mining respectively. This situation illustrates the division of the Western allies: despite shared concerns about access to metals, they are having strong disagreements over the development of undersea resources.

Finally, the “Global South”, a heterogeneous group not aligned with Western countries, is deeply divided over the exploitation of the seabed. China and Russia are fervent supporters of exploitation: having already signed exploration contracts for all types of deposits, they would enjoy a technological lead if approved by ISA. On the other hand, Brazil opposed mining projects in 202323, citing a lack of sufficient knowledge and calling for a 10-year pause in exploration. Chile, a supporter of the moratorium along with Costa Rica, fears competition for its copper reserves, which currently account for 20% of the world’s land-based reserves. The African countries, for their part, have no clear position: despite criticism, they have jointly called for a system of financial compensation24 in the event of exploitation to offset losses in their own mining sectors. No formal opposition, then, but a demand for compensation for their own mining industries. So the motivations on both sides of the divide are diverse: access to new resources, technological superiority, a source of intelligence for supporters versus a risk to marine biodiversity, priority to protection and fear of economic competition for detractors. The challenge of opening a new extractive frontier is creating major rifts within traditional alliances and upsetting the old coalitions.

In conclusion, the seabed is emerging as a new geopolitical arena, with its own rationales and fault lines. As is typical of modern geopolitics, the role of states is being scrutinized. Businesses have a key role to play in such a sphere. Indeed, they can push for the exploitation of the seabed which will benefit them directly, as The Metals Company25 has done. But they can also restrict the economic interest of these new resources by opposing their use, as demonstrated by 49 international companies that have signed a declaration in favour of a moratorium. Additionally, the proactive role of NGOs under the umbrella of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition and the mobilization of the scientific community and civil society influence certain states, starting with France, to reverse their stance in favour of a moratorium on seabed mining. It remains to be seen whether the forthcoming ISA negotiations this summer will reflect this range of positions.