835,000 km3 of freshwater are available to mankind worldwide. Mostly stored in underground aquifers (630,000 km3), freshwater is a largely renewable resource that is sufficient to meet the needs of humans and ecosystems… in theory1. So, what’s the problem ? Water resources are unevenly distributed in space and/or time. Four billion people live at least one month a year in conditions of serious water shortage, because demand exceeds availability. All year round, 500 million people suffer from this situation, which is getting worse.

Decreased water availability

Bertrand Decharme explains, “the most arid regions, including the Mediterranean basin, the eastern United States, southern Africa, south-east Asia, and India, are drawing heavily on water resources that are diminishing over time.” On a global scale, the availability of water on the continents is decreasing. The balance of arrivals (rainfall) and departures (evapotranspiration) amounts to around ‑1 mm per year between 2001 and 20202, reflecting a deficit.”

However, this average covers up major disparities. In particular, the effect is largely visible in the southern hemisphere (-3.5 mm/year). What’s more, while these variations in annual averages may appear small, they can mask an increase in seasonal contrasts3. For example, according to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)4, there has been an increase in the frequency and severity of droughts over recent decades in the Mediterranean, western North America and south-western Australia. The cause : climate change. “The consequences of climate change on terrestrial ecosystems and human societies are mainly manifested through changes in the water cycle”, writes the IPCC in its latest report.

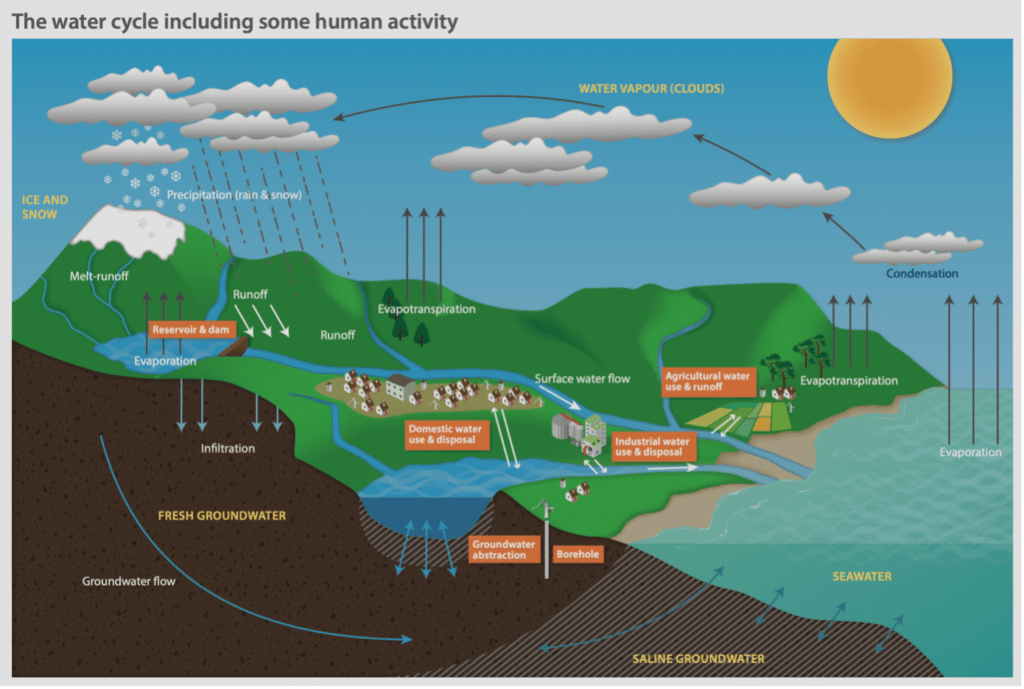

Before going into detail, let’s emphasise one point : the direct impact (excluding climate change) of human activities is by no means a secondary consideration. Since the second half of the 20th Century, the rivers feeding the Aral Sea have been diverted for irrigation, leading to it almost entirely disappearing. It has been clearly established that groundwater use for irrigation is now leading to a significant reduction in the resource ; a decline that is being felt in the world’s most productive agricultural areas, such as California, the great central plains of the United States, the plains of northern China and the Ganges basin in India6. Groundwater use guarantees food and health security in these regions. However, they can also be used for unsustainable agricultural exports. Overexploitation of aquifers makes these production methods vulnerable, and greatly reduces the expected social benefits.

On a global scale, only the equivalent of 6% of the annual recharge of groundwater is extracted each year. But here again, there are major regional disparities. “In a few aquifer basins in arid zones or in South-East Asia, withdrawals for irrigation are higher than recharge, and groundwater levels are falling,” says Bertrand Decharme. “Even though these basins are few in number, the effect is so strong that we can see it even when we look at global water resources!” Hervé Douville adds, “with climate change, the dry seasons are getting drier and drier, and irrigation is on the increase. Unless we adapt our agricultural production systems, the impact of irrigation on the water cycle is likely to increase in the future.”

Changes in land use also affect water resources. Large-scale deforestation reduces evapotranspiration (the evaporation of water from the soil) and generally precipitation. Conversely, urbanisation favours local rainfall and reduces groundwater recharge because of impermeable soils. These effects are of the same order of magnitude as the impact of irrigation. By 2050, water consumption could increase by 20–30%. As a result, human activities could become the dominant cause of future global water shortages, all the more so if mitigation efforts are implemented to limit global warming.

More extreme rainfall

Climate change is exacerbating the impact of irrigation by profoundly altering the water cycle. The first major effects are on rainfall. As the atmosphere warms, its maximum water content increases by an average of 7% for each degree of warming. This encourages an increase in average precipitation of between 1% and 3% for each additional degree. Above all, extreme precipitation will be more intense, by around 7%. The IPCC points out that the severity of extreme wet and dry events increases with global warming. “In simple terms, water resources should increase where there is already an abundance of water, and decrease where it is needed, with a few exceptions,” comments Bertrand Decharme. Aridification will particularly affect the Mediterranean, south-western Australia, south-western South America, South Africa, and western North America.

The severity of agricultural droughts may increase, and forest fires may multiply.

The combined effect of changes in rainfall and irrigation can already be seen on some water tables. Between 2001 and 2010, the decline exceeded 20 mm per year in some aquifers (California, Middle East, Sahara, Ganges, northern China).It is less marked (less than 10 mm per year) in the Amazon and Mekong basins.

The rise in global temperatures, caused by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, is giving rise to another phenomenon : the increase in evapotranspiration. This phenomenon refers to the water that evaporates from the soil and the surface of rivers, lakes and oceans, and the transfer of water from the soil to the atmosphere by plants. It is limited by the water resources available. “This is an important effect for understanding changes in water resources in soils and surface reservoirs,” adds Hervé Douville. “Even if water vapour increases in the atmosphere, the drying out of soils caused by global warming offsets this effect in the lower layers of the atmosphere above continental surfaces7.” As a result, the severity of agricultural droughts may increase and forest fires may multiply.

At this stage, it is difficult for the scientific community to accurately predict the future of water resources. The various factors involved – precipitation, evapotranspiration, irrigation – vary from region to region and according to international and regional socio-economic choices. Evapotranspiration is very likely to increase at continental level, and annual precipitation is likely to increase by 2% to 8% between now and 2100, depending on the GHG emission scenarios. “Climate models are getting better and better at predicting precipitation, but direct anthropogenic factors, such as withdrawals, are not always taken into account or are poorly anticipated,” explains Bertrand Decharme. The researcher and his colleagues have incorporated irrigation into the climate projections traditionally used by the IPCC. They are studying the 218 largest aquifer basins in the world, over which 50% of the world’s population is expected to live by 2100. By the end of the century, almost 18% of the world’s population is likely to be directly affected by a drop in aquifer levels (compared with 9% if irrigation is not taken into account8). Groundwater quality is also likely to be degraded by increasing soil pollution, higher rainfall intensity and extreme events that leach contaminants (pesticides, fertilisers, antibiotics) into aquifers.

One thing is certain, however, according to the latest IPCC report : “The future security of water resources will also depend on changes in socio-economic factors and governance”. By reducing the activities that are responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, and by limiting the way we use water, the pressure on water resources can be kept under control.