Water, a precious resource fundamental to life and all forms of civilisation, is at the heart of some of the most pressing issues of our time. In an era where climate change and resource depletion dominate global discussions, water security has emerged as a pivotal challenge for humanity. Defined as the availability of an acceptable quantity and quality of water for health, livelihoods, ecosystems, and production, coupled with an acceptable level of water-related risks to people, environments, and economies1. As such, it is strongly related to the notion of water stress, a measure of the pressure that human activities exert on natural freshwater resources2.

Recognising its vital role, the United Nations established it as one of its sustainable development goals, SDG6, aiming to ensure the safe access to water and sanitation for all. From sustaining agriculture, the pillar to food security, to supporting growing urban populations and energy production, water’s role in society cannot be overstated. However, various risks, enhanced by climate change, threaten this resource and its security.

The United Nations 2023 World Water Development Report3 highlighted the key role sustainable water management plays in safeguarding food and energy security, supporting human health and livelihoods, and mitigating climate change impacts. It is indeed key to food security, being the first pillar agriculture relies on and without which entire populations risk facing famine. It was estimated that 691–783 million people in the world faced hunger in 20224. Increasing water stress and uncertainty will only worsen this situation, posing great threats to human life, impacting food security, malnutrition, and the stability of affected regions.

Water security is not only vital in providing food and sanitation, but also a necessity to maintain peace and stability in the world.

Indeed, water security is not only vital in providing food and sanitation services to populations, but it is also a necessity to maintain peace and stability in the world. Pedro Arrojo-Agudo, the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation, stated that “Lack of clean water leads to despair, degradation of trust in institutions, mass migration, violence, and destabilisation of entire regions.” Conflicts risk arising or worsening in regions facing water shortages. For instance Somalia, a country affected by conflicts and poverty, greatly depends on agriculture with livestock accounting for almost 40% of its GDP. The country is particularly vulnerable to droughts, which have become significantly more frequent in the past 30 years. Studies suggest that these droughts have worsened violence in the country, with some drought-affected farmers and herders turning to illegal activities to compensate for their revenue loss or supporting rebel groups in exchange for cash revenues5. “Boko Haram was born where there was no water” [translated citation], stated Abdoulaye mar dieye, UN Special Coordinator for development in the Sahel during a conference that emphasised the role of water for peace in the Sahel region.

This risk of an increase in tensions not only entails internal instability, but also international diplomatic tensions. Indeed, freshwater sources like rivers and lakes, does not recognise borders, often making it the subject of international tensions and conflicts. More than 60% of all freshwater sources are shared by at least two countries6, highlighting the need for cooperation between countries on the matter. “Conflicts over water will become more common without science-based water diplomacy”7.

Increasing demand

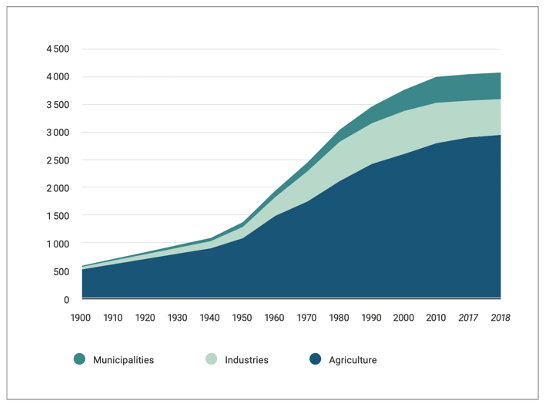

Globally, water use has been increasing by roughly 1% per year over the last 40 years, with a large part of this increase concentrated in middle- and lower-income countries, particularly emerging economies. This trend has been driven by a combination of population growth, socio-economic development and changing consumption patterns. Three major sectors are responsible for water use and consumption: Agriculture, Industries, and Municipalities.

Between 2010 and 2018, municipal water withdrawals increased by 3%, while Agriculture withdrawals increased by 5% to represent 72% of current total withdrawals. During the same period, industrial withdrawals decreased by 12%, mainly due to more water-efficient cooling processes in thermal power production. Tensions and trade-offs in water supply between agriculture and cities have been growing. This is partly due to rapid urbanization, with urban water demand projected to increase by 80% by 2050.

Diminishing per capita resources

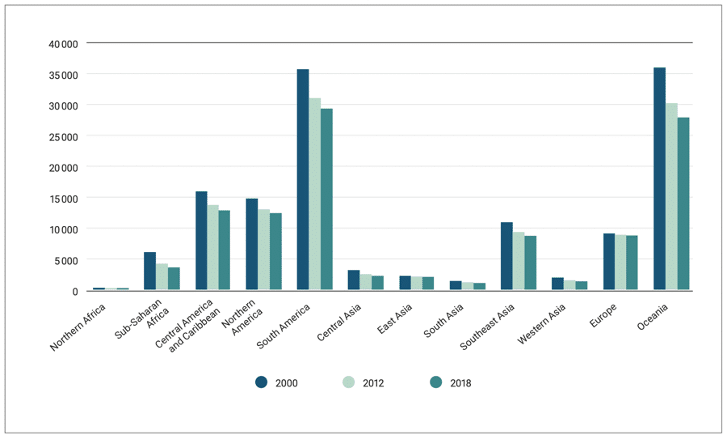

Simultaneously to this global demand increase, available freshwater resources have been decreasing over the last 20 years. Between 2000 and 2018, global per capita internal renewable water resources (IRWRs) decreased by 20%.

This decline has most affected countries with the lowest resources to start with, often located in Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. In sub-Saharan Africa, water availability per capita declined by 40% over the past decade. However, such global statistics can be misleading, hiding the very local issues of water stress. Effects can be highly disparate, varying significantly within single regions and countries, and with high seasonal variability. Water is a local issue, which is why it is essential to consider it as such and delve into its direct impact on populations.

Water stress in the world

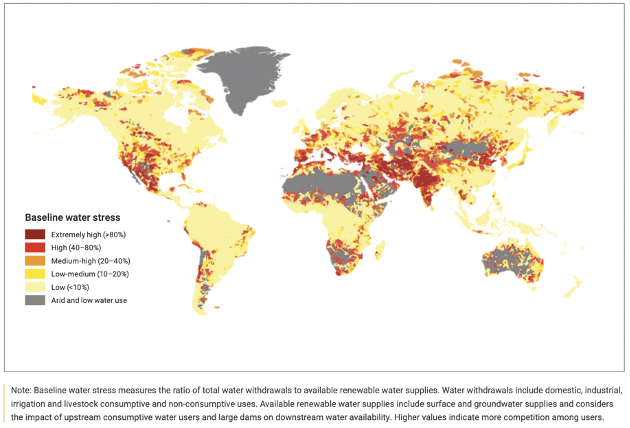

More than 733 million people live in countries with high (70%) or critical (100%) water stress, accounting for almost 10% of the global population. Baseline water stress measures the ratio of total water demand to available renewable surface and groundwater supplies.

About 1.2 billion people live in areas where severe water shortages and scarcity challenge agriculture and where there is a high drought frequency in rainfed cropland and pastureland areas or high water stress in irrigated areas. Northern Africa, Southern Africa, and Western Africa each have less than 1 700 m3/capita, which is considered to be a level at which a nation’s ability to meet water demand for food and from other sectors is compromised.

Scarcity vs Security

This physical water stress or scarcity, measured by a ratio of water demand over available renewable resources, describes a mismatch between the demand for freshwater and its availability. Water security is a broader concept, encompassing access to water services, safety from poor water quality, and appropriate water governance ensuring access to safe water8. For instance, physical scarcity does not account for economic water scarcity, describing a situation in which there are sufficient resources to meet human and environmental needs, but access is limited due to a lack of water infrastructure or poor water resources management.

In addition to the 1.2 billion people living under conditions of physical water stress, an estimated 1.6 billion people face conditions of economic water scarcity)9. This includes cases of mismanagement leading to pollution of water sources, an unregulated water use from agriculture or industry, and major inefficiencies in water use. Indeed, the increase in physical water stress is coupled with the acceleration of freshwater pollution, threatening even more drinking water resources, with significant impacts on both the environment and human health. UNEP estimates that 4,000 children die every day from diseases caused by polluted water and inadequate sanitation. A major example of inefficiency can be found in agriculture, which consumes 70% of global freshwater resources. Some 60% of this is wasted due to leaky irrigation systems, inefficient application methods as well as the cultivation of crops that are too thirsty for the environment in which they are grown10.

Furthermore, climate justice has been an increasingly discussed topic at the COPs, acknowledging the fact that countries suffering the most from the consequences of climate change are not its main contributors. On one hand, the richest countries representing 16% of the world population are responsible for almost 40% of CO2 emissions. On the other hand, the two categories of the poorest countries in the World Bank classification account for nearly 60% of the world’s population, but for less than 15% of emissions11.

Since developing countries are often the most affected by droughts and water scarcity, they are often also the ones for which the economy depends the most on the agricultural sector, intrinsically reliant on water supply. Their economies are therefore the most impacted by increasing uncertainty on water supply, while they are precisely the ones with the biggest need for economic growth to improve living standards. Without international solidarity, these countries have limited economic means to build resilience and adapt their water and agricultural systems. In addition, the lack of adequate access and capacities to take advantage of natural capital can lead to an overuse and exploitation of non-renewable resources to meet short-term needs, worsening future threats.

Various types of solutions to water scarcity were discussed during COP28, from technical innovations enhancing water efficiency to investment in infrastructure to avoid water loss from leaking and evaporation. There is no ‘one size fits all’ prescription12 to address water scarcity, the complexity of very local water-related issues translating itself into the multiplicity of existing and potential solutions. However, one common pillar to all projects, frequently mentioned during COP28, is the need for an integrated and holistic approach in partnerships.

For instance, a side event hosted by the European Pavilion stressed the role of this integrated approach and of inclusiveness in mitigating water-related risks. The lack of progress towards SDG6 highlighted the need for partnerships and collaboration. Indeed, nearly every water-related intervention requires some form of partnership, and any progress towards SDG6 heavily relies on the efficient and productive performance of partnerships.

The pursuit of water security is a shared responsibility that involves governments, communities, and individuals.

Water systems are interconnected with various environmental, economic, and social systems. Due to this interconnectedness and complex hydrology, a holistic approach that considers all facets of water systems and their interdependencies is essential. One essential aspect of this holistic approach is to consider the various actors involved in partnerships, with sometimes different water-related goals, requiring an inclusion of all their voices to ensure a coordinated approach in facing water scarcity. Taking into account all perspectives of involved actors helps determine a clear, shared vision of the objectives, outcomes and results, based on a common understanding of the problem. For instance, a major topic discussed during COP28 was the inclusion of local and indigenous communities’ voices in partnerships for adaptation.

Their knowledge and perspectives are essential, with a profound understanding of their environment and ecosystem dynamics. They are often on the front lines of climate change and its consequences on water, and their involvement ensures water security efforts answer to the specific challenges they face, that no one is left behind and that the human rights to water and sanitation are brought to fruition.

The discussions at COP28 in Dubai have brought to the forefront the critical issue of water security. “Development banks have made water one of the priorities of this COP”, insisted Ambroise Fayolle, Vice President of the European Investment Bank, during an event held at the Water for Climate Pavilion.

Nevertheless, addressing water scarcity and the challenge of freshwater pollution requires comprehensive and strategic solutions. The importance of governance, coupled with the need for innovative partnerships and integrated resource management, has been clearly identified as a critical path forward. COP28 discussions emphasised the need for a holistic approach in tackling water security. This approach should include all stakeholders, including local and indigenous communities, recognising that those directly affected by water scarcity often hold essential insights into sustainable management practices.

As global efforts continue towards achieving Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG6, the insights from COP28 serve as a guide for future actions. The pursuit of water security is a shared responsibility that involves governments, communities, and individuals. It’s an issue that entails environmental, economic, and social considerations, touching on the fundamental rights of all. The path to ensuring a water-secure future requires collective and coordinated actions.

The UN water development report estimated that at current rates, progress towards all the targets of SDG 6 is off-track, with some areas for which the rate of implementation needs to quadruple or more. Therefore, we are far from being on track with the necessary change, but the numerous events organized around water security during COP28 highlight the increasing importance of the topic in global negotiations and give hope for ambitious action at the COP29 taking place in Azerbaijan.