Quantum computers: how do they work?

This article is part of our special issue « Quantum: the second revolution unfolds ». Read it here

Universities and laboratories around the world, as well as the big tech companies, Google, IBM, Intel and Microsoft, are studying and developing quantum computers at breakneck speed. The stakes are high. But what exactly is this technology?

A quantum computer is not really a ‘computer’ as such, but rather a super-calculator, capable of running specific powerful quantum algorithms much faster than an ordinary processor. It does this using the principles of quantum mechanics, which are responsible for the behaviour of elementary particles such as photons, electrons and atoms, but also of larger systems such as superconducting circuits.

Such systems allow for the implementation of quantum bits (‘qubits’): two-state quantum systems that represent the fundamental computational bricks of quantum information.

Unlike conventional computers, which encode information in binary form, qubits are not limited to ‘0’ and ‘1’ but can be in any combination (or ‘superposition’) of the two. This ability, combined with the fact that N qubits can be combined or ‘entangled’ to represent 2N states simultaneously, allows calculations to be performed in parallel on a massive scale. A quantum computer could therefore, in principle, outperform a classical computer for some important tasks, such as sorting large unsorted lists or for ‘prime factorisation’. The latter forms the basis of most encryption algorithms in use today – in particular for banking operations.

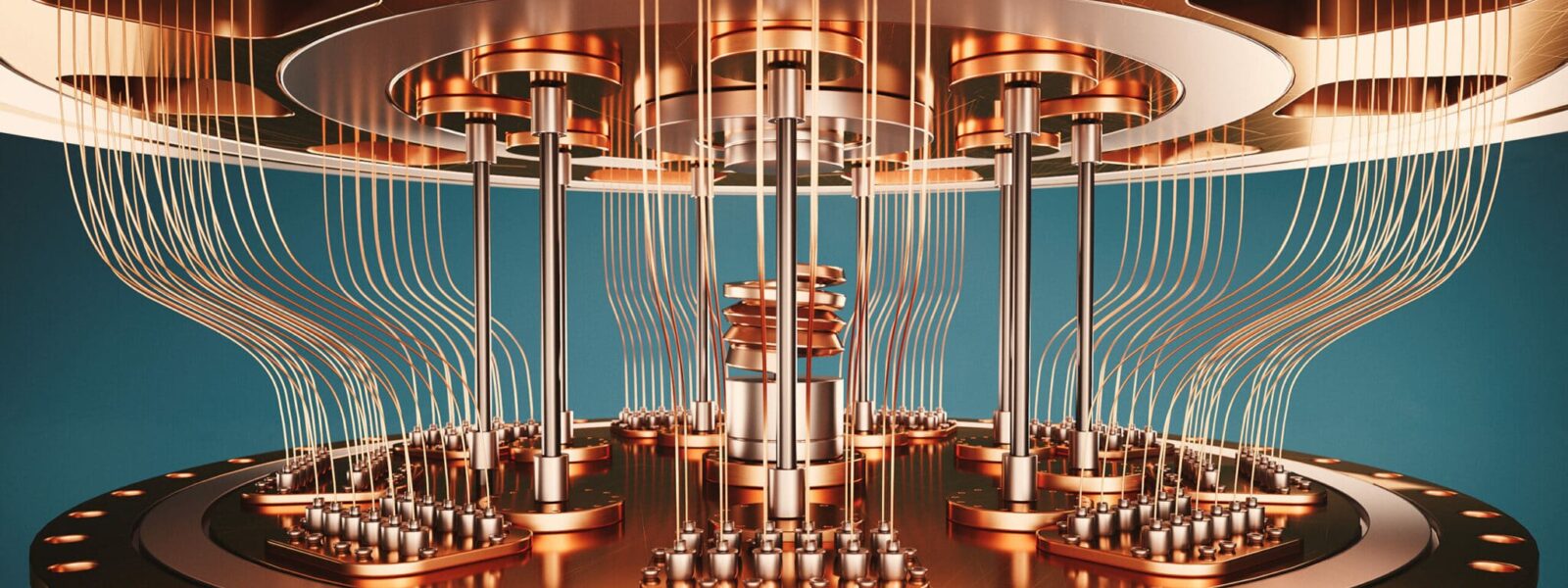

Quantum computers look more like large cans, suspended from the ceiling, cooled to near absolute zero with hundreds of cables hanging from them.

Quantum computers don’t look anything like their classical counterparts either. Current models look more like large cans that are suspended from the ceiling, cooled to near absolute zero (-273.14°C), with hundreds of cables hanging from them.

The bane of quantum computers: decoherence

Anyone wishing to build a quantum computer today must first overcome a big problem: the fact that qubits are extremely fragile. Almost any interaction with external ‘noise’ in their environment can cause them to collapse like a soufflé and lose their quantum nature in a destructive process known as decoherence. If this happens before an algorithm has finished running, the result is a complete mess (and not the result of a calculation) because any information stored in the qubit is lost (imagine a computer that has to restart every second). And, the more qubits a quantum computer has, the more difficult it is to keep them coherent. So much so that even the most advanced quantum processors today struggle to surpass 60 physical qubits. A real device would require several thousands, however.

Because of this problem, a quantum computer must be well isolated from its environment. This requires very stringent conditions: simple and very cold systems, protected from the outside world. Such extreme confinement creates a paradoxical situation, however, because the more isolated the computer is, the more difficult it is for us to actually communicate with it (to access the results of its calculations) and control what it does.

Tackling decoherence

In recent years, qubits have been made from a number of isolated systems that remain coherent while algorithms are being run. These include trapped ions (atoms with an electron removed or added), ultra-cold ‘Rydberg’ atoms, and photons (light particles).

A trapped-ion based computer stores information in the energy levels of individual ions. This is how qubits are formed in this system. Information is shared between these qubits, and laser pulses are then used to manipulate their states and create entanglement between them. This technology is quite advanced and researchers have recently succeeded in creating a fully entangled ‘24-qubit-GHZ’ (GHZ for ‘Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger’) state using calcium ions1.

Other systems are based on solid-state materials that might be integrated into traditional electronic devices. These micron-sized structures are small on everyday scales, but large compared with atoms and can behave like quantum particles, such as electrons or atoms. Such ‘artificial quantum objects’ include ‘quantum dots’ (tiny pieces of semiconducting material), superconducting circuits, and diamonds containing special type of defects called ‘nitrogen vacancies’. A quantum computer based on superconducting qubits, for example, is cooled down to millikelvin temperatures (which is colder than interstellar space) and is controlled using microwaves2.

Researchers are also trying to work out which of these systems would make the best qubits. An important parameter is, of course, a qubit’s resistance to decoherence, which can be assessed in terms of the ‘fidelity’ of a quantum operation. While the fidelity does not have to be a perfect 100%, anything lower will eventually lead to errors after multiple operations; most of today’s quantum computers are very susceptible to errors.

Although ‘quantum error correction’ protocols can mitigate decoherence, these are costly from a hardware point of view and any practical system must have a sufficiently high fidelity to begin with. Researchers are making progress in this area, however, and recent work has shown that a two-qubit gate can be made from two silicon quantum dots3. This gate can achieve 98% fidelity for the CROT operation, which an essential component of a quantum computer.

What can quantum computers realistically achieve today and what lies ahead?

The idea of a quantum computer was first put forward by the late physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman in the 1980s to simulate the complicated equations of quantum mechanics, which take too long to solve on a classical computer. Today, application areas are much more varied: cryptography; simulating the properties of materials (with a view to improving them); solving differential equations extremely quickly; and optimizing machine learning. Progress has been impressive and researchers have gone from being able to entangle just three qubits to more than 50 qubits in recent years, with error rates of 1 in 10004.

Although it is difficult to predict what the future holds, a fully functional, commercially viable quantum computer is unlikely to see the day of light anytime soon. The same goes for any kind of ‘personal quantum computer’. A quantum device will more likely be used for fundamental research, R&D or government and military purposes to begin with.

Today, researchers in this field are not only advancing hardware (i.e. the machines themselves), but are also developing innovative software with new types of algorithms especially adapted to quantum computing.

While quantum computing relies on the principles of fundamental physics, it is a tremendous opportunity for scientists from many fields – including computer science, mathematics, materials science and engineering – to work together. The road to a real-world quantum computer will certainly be long, but there will be many exciting discoveries along the way.

Interview by Isabelle Dumé