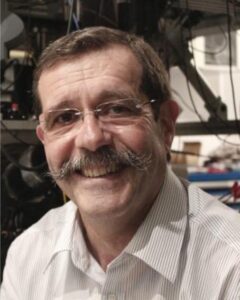

This article is part of our special issue « Quantum: the second revolution unfolds ». Read it here

Quantum physics is the set of physical laws that govern the behaviour of the world at the level of electrons, atoms, molecules and crystals. The laws of Newtonian mechanics that we are familiar with on our own scale are no longer valid at the nanometre scale (one billionth of a metre), which corresponds roughly to the size of an atom. Quantum physics began to be developed in the first quarter of the 20th Century with Planck and Einstein, and from 1925 the great physicists Heisenberg, Schrödinger and Dirac developed a mathematical formalism that has been in use ever since.

Quantum physics is essential, for example, to explain why matter is stable. Since the end of the 19th Century, we have known that matter is made up of positive and negative charges, and that these positive and negative charges attract each other. Matter should therefore collapse in on itself. This is not the case thanks to the quantum behaviour of the electron, which is not just a particle, but also a wave. When you try to confine an electron, you are forced to consider an ever-smaller wavelength and therefore ever-greater energy. As this energy is unavailable, the electron cannot be confined to a dimension smaller than the size of the atom. Quantum physics can also be used to understand the chemical bonds between atoms.

Its formalism makes it possible to describe the electric current in materials at the microscopic level too, something that has enabled physicists to invent and manufacture transistors and integrated circuits, which are the basis of computers. It also allows us to understand how photons (particles of light) are absorbed or emitted by matter, which was essential for inventing the laser.

What about quantum computers?

The concept of the quantum computer emerged over the last two decades or so and was triggered by several experimental breakthroughs made from the 1970s onwards: the first was that we learned to observe and control individual microscopic objects. Previously, we could only manipulate large ensembles of particles. Today, we can trap an electron or an atom and observe and control it. We can also emit a single photon and make use of it.

The second series of advances is linked to quantum entanglement, described for the first time in the 1935 article by Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen, and which is only conceivable within the framework of quantum physics.

Entanglement occurs when two particles, having interacted in the past and then separated in space, form an inseparable quantum whole that contains more information than that contained in the sum of the information of each particle. It is this property that opens the door to quantum computing: if instead of having just two entangled quantum bits in which to encode quantum information, you have three, four, five, 10 or 100, the additional quantity of information, compared with a classical memory, contained in these particles is gigantic because it grows exponentially.

Decoherence is a major stumbling block

Today, however, we are still a long way from a perfect quantum computer because the quantum bits (qubits) we have are not stable and undergo what is known as “decoherence” when they interact with their environment. This means that after a certain time they behave like classical objects and lose the quantum information they contain. Decoherence is an obstacle to the creation of a quantum computer and will require a major technological effort to solve. But there is nothing to prevent us from overcoming the difficulty faster than expected. For example, we could find a subspace of quantum states protected from decoherence. If that were the case, we could see a quantum computer in my lifetime.

I’m convinced that sooner or later an ideal quantum computer that works perfectly will exist, because in my experience, when something that seems feasible is not forbidden by the fundamental laws of physics, engineers eventually manage to find a way of making it happen. Realistically, though, I’d be surprised if this happened in the near future.

A future quantum network and teleportation

A quantum internet, or if we want to be more precise, a quantum network, would make use of two or more quantum computers communicating with each other by sending quantum information directly from the quantum state, without having to pass through an intermediate classical state. This would enable a very large amount of information to be transmitted. This can be achieved by a process known as quantum teleportation, which has already been demonstrated for individual particles and small ensembles of particles, but over distances of no more than a few tens of kilometres.

If the decoherence problem is not solved in the near term, a class of “degraded” quantum computers will probably appear first. These intermediate-scale machines will be much more efficient than a conventional computer for certain tasks, such as optimisation problems (the famous travelling salesman problem, for example, or the optimisation of electricity networks).

The second quantum revolution

Today we often hear talk about “quantum 2.0”, but I prefer to call it “the second quantum revolution”, because it is a radical revolution. The first quantum revolution was primarily conceptual and scientific, the implementation of a new mathematical formalism to describe wave-particle duality. It led to a much better understanding of the physical world, and to applications that have revolutionised society. The second revolution is based on two new concepts: our ability to isolate and control individual quantum objects; and the possibility of entangling these objects and exploiting this entanglement in real applications.

Will these new quantum technologies revolutionise our society in the same way as the transistor and the laser? It’s too early to say, but I think it’s important for companies to invest in these technologies, because if they really do bring the revolutionary advances we’re expecting, those who don’t invest will be out of the game. It will be important to have in-house experts in quantum physics capable of rapidly exploiting these advances. Today, there is a shortage of people with skills in quantum physics, and I think that entrepreneurs need to join forces with universities to deal with this problem more effectively.

At Paris-Saclay, for example, we have a programme called ARTeQ, with which Ecole Polytechnique (IP Paris) is associated. Several industrialists provide financial support. ARTeQ enables students in the sciences, but not necessarily in the quantum sciences, to acquire a good grounding in quantum culture so that they can apply the knowledge they acquire in their future careers.

We need quantum researchers, engineers and technicians. So, my message is: invest in research, technology and training.