Why are scientists honing in on telecommunications cables at the bottom of the sea?

- Fibre-optic cables on the seabed and coastlines are used for telecommunications around the world.

- Scientists in a variety of fields using them to harvest seismo-acoustic waves from the ocean floor.

- Already installed, these ‘sensors’ are reliable, inexpensive, and continuously available in real-time.

- In practical terms, this tool will make it easier to study and predict earthquakes, characterise storm dynamics as well as study whales.

For some years now, fibre-optic telecommunications cables have been appearing in scientific publications in unexpected disciplines: earth sciences, oceanography, ecology… What exactly are these cables?

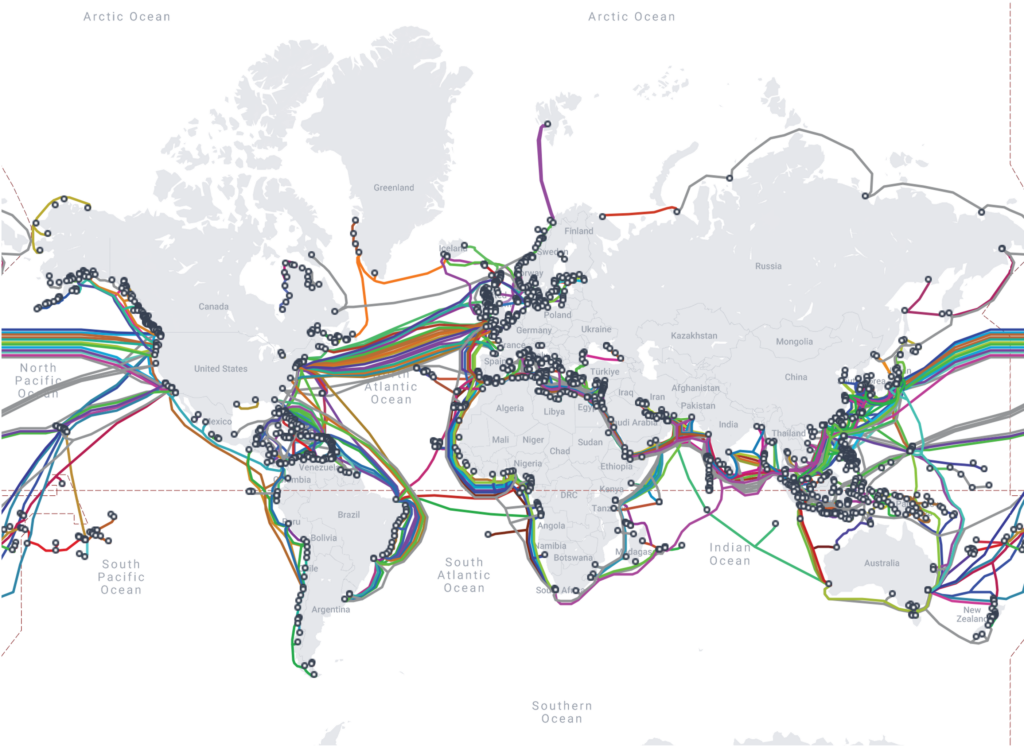

They are telecommunications cables used by the scientific community. Located on the ocean floor (particularly in the Pacific and North Atlantic) and along the coast, they carry global telecommunications. They are widely, but unevenly, distributed across the globe. Each submarine cable is made up of around fifteen glass optical fibres. We are diverting them from their telecommunications use to retrieve a wide range of scientific data. It is also possible to take advantage of underground terrestrial cables, and we have a project along these lines with the Nice metropolitan area.

What data can be recovered using fibre optic cables?

We measure the deformation along the cable every metre. This allows us to detect seismo-acoustic waves, precisely those that propagate during an earthquake. In practical terms, thanks to this technology, with a single cable we have the equivalent of hundreds of seismometers deployed on the ocean floor. We have also recently demonstrated that it is possible to measure temperature, to a sensitivity of the order of 0.001°C1. This crucial data was previously unavailable at this level of detail for the seabed. It allows us to better characterise oceanic processes such as internal waves and upwelling phenomena.

The potential of this technique is enormous. It is revolutionising our vision of the environment, and its applications are extremely wide-ranging. This new tool offers, for example, the possibility of imagining real-time monitoring systems, or even warning systems. If we look at the history of science, we see that major advances are often linked to advances in observation. With optic cables, we are taking a new step forward, which suggests that we will be able to unblock many scientific questions.

Why so much enthusiasm? What are the advantages of using telecommunications cables?

The oceans cover two-thirds of our planet. But we have very few sensors on the ocean floor: instruments must be deployed offshore, then returned months later to retrieve them. This method provides one-off measurements and requires a lot of logistics and financial resources. Telecommunications cables provide an unprecedented opportunity to have many ‘sensors’ on the seabed! With a measurement every few metres along each cable, the density of sensors is phenomenal and unprecedented. In contrast, long telecom cables – over 300 km – are equipped with repeaters every 70 km or so. At the moment, it is not possible to exceed these repeaters, so we are recording measurements up to 70 kilometres from the coast. The potential is already colossal, since the economic stakes are concentrated in this zone. In the future, I’m sure it will be possible to overcome this constraint.

These cables offer a host of advantages. As they are already installed, there is no need to disturb the seabed any further. They are reliable, available continuously and in real time. As a bonus, the system is very inexpensive: it relies on the installation of an instrument costing a few hundred thousand euros. As it is equivalent to thousands of sensors, this works out at less than €10 per sensor. Finally, the sensitivity of the measurements is comparable to that of traditional sensors such as seismometers.

How exactly are these measurements taken?

It’s very easy to set up: all you must do is connect a box to the end of the earthed cable. The system consists of a laser that emits light into the cable. As the light propagates inside the optical fibre, it encounters the small nanometric-scale defects that are inevitably contained in the glass of the optical fibre. These defects reflect the light. The box records this echo and measures the relative displacement of the defects along the fibre. This type of measurement is called DAS, for Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Several manufacturers offer these systems for sale. There are other technical solutions for using optical fibres as sensors, but DAS technology is by far the most widespread.

When did the scientific community get to grips with this new tool?

In the 2010s, the first to implement the DAS system were oil companies: these cables are very useful for equipping boreholes, because they are thin and strong. But at that stage, the cable was specifically deployed for measurement. The first to come up with the idea of testing DAS on existing telecommunications cables were an American team from the University of California. In 2017, they published a paper2 that revolutionised our approach: they showed for the first time, using the telecom fibre on the Stanford campus, that it was possible to use existing telecom cables to track earthquakes. Within our team, we then rapidly launched the first trials on a telecom cable off Toulon: we confirmed the relevance of these measurements for measuring regional seismicity and wave dynamics3.

They are reliable, available continuously and in real-time.

For the moment, most academic users work in the field of seismology, probably because seismologists are very close to the petroleum geophysics community. But other disciplines are beginning to take up the technology, and the number of scientific publications mentioning DAS technology is exploding: from less than 20 in 2016 to more than 150 in 2022.

What scientific advances have made this measurement system possible?

We’re still in an exploratory phase, so we can’t say that any major scientific advances have been made thanks to DAS (yet!) However, we’re very quickly demonstrating the benefits of DAS for decrypting signals. We have proved the relevance of DAS for recording earthquakes and we are now building new catalogues of previously undetected earthquakes. For example, we have a project in south-east France and Chile to equip telecom cables and better characterise the seismic risk in the region. Thanks to these measurements, it will be possible to improve our understanding of earthquakes that take place at sea – which can be very destructive – and even to detect them in real time.

We now know that the system is also very useful for studying ocean and storm dynamics4. Surface waves, for example, generate vibrations that we can detect on the ocean floor, and we can also record deep ocean currents. These measurements can be supplemented by DAS temperature measurements. Finally, a Norwegian team has just demonstrated the value of DAS in bioacoustics5.They are recording whale songs and estimating the 3D position of the animals. There are enormous opportunities for gaining a better understanding of the interactions between cetaceans and their environment: how they are affected by anthropogenic noise, the movement of bodies of water, etc. Since DAS can also be used to detect boats, it is entirely possible to imagine setting up anti-collision systems.