The use of nuclear power in deep space exploration

- Powering space objects can be done in two ways: by finding a source of energy in space, or by taking energy from Earth.

- The two power sources currently used in space are solar and nuclear.

- The Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RGT), using radioactive materials, now provides the power for many space probes.

- But solar power is not always guaranteed, depending on the mission parameters and the environment of the scientific equipment.

- In the future, nuclear power could be used for space propulsion, in addition to chemical and electric propulsion.

There are few environments as hostile as space, and getting humans to survive there is (and always has been) a challenge. But whether exploration flights are manned or unmanned, one of the major problems is always how to power the spacecraft or probe. Up there, the word vacuum has never been more aptly named, and to carry out space activities – powering, propelling or communicating – you either have to find a source of energy locally or take it with you from Earth.

These two possibilities lead to the two sources of energy currently used in space: solar energy, which enables part of the sun’s light to be converted into electricity on site using photovoltaic panels; and the use of nuclear reactions to power and, in the future, propel spacecraft whose operating conditions do not allow solar energy to be used (or not properly).

Over 50 years of nuclear power in space and elsewhere

There are also places on Earth that are so far from civilisation, and with such extreme environments, that it is very difficult to provide a stable and reliable source of energy. Fairway Rock, for example, is a tiny island of less than 1 km² located in the icy Bering Strait off the coast of Alaska, between the United States and Russia. It was on this tiny rock, near the Arctic Circle, that the US Navy first installed a Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG) in 1966 to provide electricity for its “environmental monitoring” facilities.

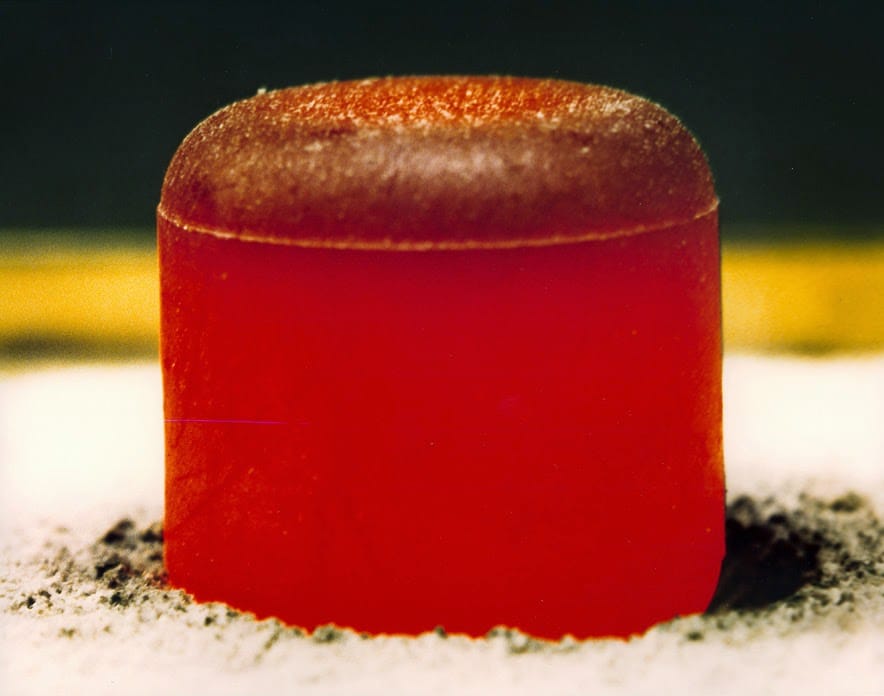

Today, this device is the key to the power supply of many space exploration probes, the most famous of which are the Pioneer and Voyager probes (which are currently leaving the Solar System) or the Cassini-Huygens probe which explored Saturn and its moons between 2004 and 2017. Although RTGs use radioactive materials such as Plutonium-238 or Americium-241, they are not considered “nuclear reactors” in the sense that they do not cause sustained nuclear fission reactions, as in conventional nuclear power plants. Instead, the natural heating of a block of radioactive material is used. And it is this heat, induced by the radioactivity, that is converted into electricity with the help of thermocouples.

Although the efficiency of this conversion is quite low (around 10%), it has the advantage of producing electricity in a stable and continuous manner for decades. Radioactive materials are characterised by their ‘half-life’, which is the time after which their radioactivity (and therefore their energy output) has halved. For Plutonium-238 (the most widely used in today’s RTGs), its half-life is ~88 years, which ensures a sufficient supply of energy for space missions whose durations typically extend over one or two decades.

Space power: solar or nuclear?

But the length of time the system provides electricity is not the only advantage of this technology. The Sun emits light continuously, allowing a mission to continue virtually forever as long as it is illuminated by light. But this is precisely where the problem lies. Depending on the parameters of the mission and the environment of the scientific equipment, the supply of solar energy is not always guaranteed.

The rovers used to explore the surface of Mars have to deal with the local weather conditions.

On Mars, for example, the rovers used to explore the surface have to deal with local weather conditions. The Red Planet has an atmosphere which, although much less dense than Earth’s (the pressure is ~200 times lower), does not prevent the sometimes very fast winds from raising the fine ochre dust that scatters its surface. It will then redeposit itself on the solar panels of human robots, sometimes almost completely blocking out the available sunlight.

In December 2022, the Insight mission to study the internal structure of Mars ended after four years of activity, its solar panels almost completely covered in dust. This is why the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, sent to Mars in 2012 and 2021 respectively, are equipped with an RTG. In addition to producing electricity, it also allows certain sensitive parts of the electronics to be heated, which do not cope well with the average Martian temperature of around ‑60°C.

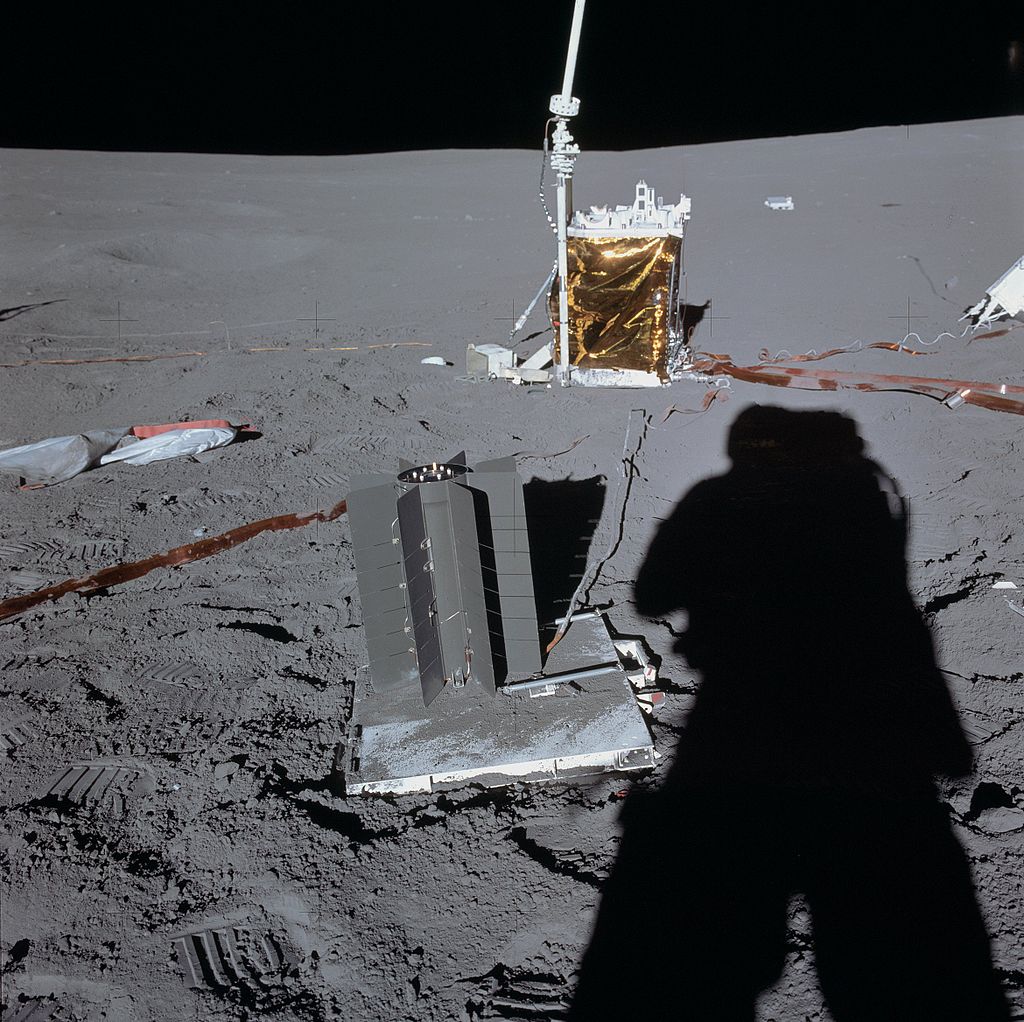

But even in environments with no atmosphere (and therefore no dust), RTGs may be necessary. During the Apollo missions to the Moon, RTGs were used to supply power to scientific instruments placed near the landing modules. The reason: some of this equipment was intended to be used continuously for more than 10 years. But a day on the Moon is much longer than on Earth. A day (between sunrise and sunset) lasts almost two Earth weeks. The lunar night lasts just as long. Solar devices would not have been able to supply electricity to the instruments for a fortnight every month, which is why RTGs are useful.

Finally, even in space, where the Sun shines continuously, it is necessary to think carefully about the type of technology that will be used to provide electricity to the exploration probes. Like any source of light, the further away we are from the Sun, the less light it gives us. And this decrease in luminosity is very rapid. It decreases as the square of the distance. If we move 3 times further away, we receive 9 times less light. If you move 10 times further away, you receive 10² = 100 times less light.

In practice, for all missions that go beyond the orbit of Jupiter, the amount of light received is so low that the use of solar panels is no longer effective. Once again, it is RTG technology that overcomes this problem, as was the case, for example, for the Cassini-Huygens mission to explore Saturn and its moons or the famous New Horizons mission which, for the first time in the history of astronautics, obtained resolved images of the surface of Pluto after 10 years of travel in the Solar System.

Nuclear propulsion

Another area of space is likely to see the arrival of new nuclear-based technologies in the coming decade: space propulsion. In this field, the principle is always the same: project as much matter as possible as quickly as possible in one direction to generate a force that propels the vessel in the opposite direction. This is the famous principle of Action-Reaction.

At present, this principle can be roughly divided into two technologies: chemical propulsion and electric (ionic) propulsion, each with advantages and disadvantages. Conventional chemical propulsion uses propellants whose combustion produces large quantities of hot gases, which are responsible for a very high thrust, but which is very limited in time (around ten minutes at the most). In addition, it requires huge quantities of fuel to be carried on board, which in turn weighs down the spacecraft, requiring more fuel to be used… to propel this fuel.

In contrast, ionic propulsion consists of accelerating an ionised gas between electrically charged grids. The speed at which the particles leave the space no longer depends on a particular chemical reaction but on the intensity of the electric field that is created. The speed of the particles is potentially much higher, which allows the amount of fuel used to be drastically reduced. An ion engine uses about 100 grams of fuel per day, whereas the Ariane rocket consumes several hundred tonnes of propellant per second. This ion drive is more efficient and can be used continuously for several weeks or months at a time.

The disadvantage is that it generates extremely low thrust (a few newtons at the most), which imposes major constraints on the types of aircraft on which it can be used. Nuclear thermal propulsion, on the other hand, involves using a propellant fluid (hydrogen, for example) and heating it by passing it through the core of a nuclear reactor. It can then be expelled at high speed, in large quantities, to propel the vessel. In terms of efficiency, nuclear propulsion is between chemical and ion propulsion, theoretically allowing for very high gas ejection rates, while supporting very long thrust times.

In 2021, NASA selected three business conglomerates to carry out concept studies for nuclear thermal propulsion reactors (BWX Technologies/Lockheed Martin, General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems/X‑energy/Aerojet Rocketdyne and Ultra Safe Nuclear Technologies/Blue Origin/General Electric Hitachi Nuclear Energy/General Electric Research/Framatome/Materion). The work is ongoing. At the end of January 2023, Bill Nelson, the current NASA Administrator, announced a collaboration with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to “develop and demonstrate advanced nuclear thermal propulsion technology as early as 2027”.

Europe, meanwhile, produced a report in 2013 called « Megahit » that proposed a roadmap for the development of space-based nuclear systems. However, it has not led to any publication since. One of the main problems in the development of these nuclear-based space technologies is of course the security and societal aspect. It is relatively easy today to build RTGs in which the small radioactive pucks are protected by successive layers that ensure good heat transfer while at the same time providing the best possible resistance to events such as the destruction of the launch vehicle at lift-off or uncontrolled atmospheric re-entry. This happened in April 1970 when the Apollo 13 mission returned to Earth in an emergency following the explosion of part of the spacecraft. After withstanding the heat of re-entry without breaking, the RTG responsible for powering the instruments on the Moon plunged into the Pacific Ocean over the 10 km deep Tonga Trough.

On the other hand, it is difficult, given the state of development of future nuclear-powered engines, to establish how such much larger and more complex craft could provide the same level of safety. However, this is a crucial step that must be taken if this kind of new space propulsion technology is to be developed and Mars is to be reached in much less time than it takes today.