If the metaverse has been all the rage for less than a year, it’s because Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and President of Facebook, has been talking about it all the time. In reality, the concept dates back to 1992, when the American writer Neal Stephenson drew the outlines of it in a science fiction novel entitled The Virtual Samurai. Metaverse comes from “meta”, which means “beyond” in Greek, and “verse” corresponding to “universe”.

Facebook and its metaverse

A metaverse, then, is what encompasses all virtual universes. When Mark Zuckerberg mentions the subject, he is obviously presenting his vision, a direction in which all virtual universes, including existing metaverse, would be included in his own. This is a prospect that may never materialise, as such compatibility between all metaverse models will take years to achieve – if it is achieved at all. There is little chance that the Chinese internet will become compatible with a single virtual universe, that of Facebook/Meta.

In my view, there are two main biases in the future Mark Zuckerberg has outlined. The first concerns the foundations of a project based on audience, advertising, NFTs and video games. Before being a film by director Steven Spielberg, Ready Player One was a social science fiction novel by author Ernest Cline. A few months before publishing his book, the author wanted to compare his vision of the metaverse with that of the Californian start-up world. He went to meet both Mark Zuckerberg and Palmer Luckey, the young creator of the Oculus company, which had just brought virtual reality headset technology up to date with the computer technology of the time. Ernest Cline adjusted the characteristics of the metaverse described in his novel after these two meetings. The following year, Facebook bought the company Oculus for $2bn. The plan to create a fun and profitable metaverse had already been in the works at the American company for a long time.

The second way in which this vision is biased is apparent in Mark Zuckerberg’s speech, when he gives the impression that you absolutely need a virtual reality headset to enter the metaverse. We can understand why since he now has VR headsets to sell. But, in reality, there are no prerequisites in this respect. To enter a metaverse, all you need is a connected flat screen (PC or Mac web access, mobile, etc.), a simple integrated camera and an avatar. Moreover, the video game industry did not wait for virtual reality headsets to create immersive experiences.

Just a virtual world

The definition of the metaverse is much simpler in reality. It is a persistent virtual universe, permanently open, where each individual/avatar can go to be in the company of other people who are themselves distant from each other. This is the promise of the metaverse. To keep it, there is no need for helmets, but for cognitive sciences. The metaverse relies on what is known in cognitive science as “virtual presence”. It must recreate a feeling of real presence in a virtual environment. This feeling is based on three pillars.

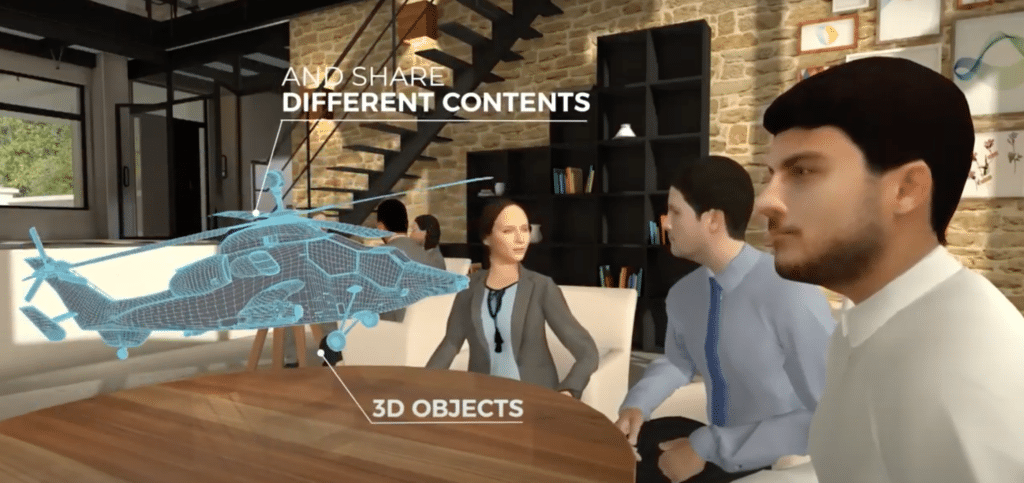

The first is the feeling of being present in this universe. Scientific studies prove that the more the avatar resembles us, the easier and faster we become integrated into this virtual world. With Manzalab, we created the Teemew platform, a corporate metaverse specialised in the world of business and training. In Teemew, we have integrated a module where you can, from a simple selfie, create a photorealistic 3D avatar very quickly and easily, a guarantee of success in this search for self-presence.

The second pillar of the metaverse is the sense of spatial presence, i.e. the environment in which the avatar is located. What cognitive science still advocates is that it should be realistic, as credible as possible. This sometimes requires working with real architects to establish some resemblance with the real world. Of course, it is quite possible to gather avatars on the ground of Mars, but this would be counterproductive, as the participants’ attention would then be diverted by this dissonant environment.

Finally, the third and last pillar is to create the impression of the presence of others, the feeling of community, and it is based on the means of communication available to the participants. However, we must be clear: we can never achieve the intensity of the feeling of presence of the real world. But we can come close by making communication as natural as possible and by regaining a sense of informality. For example, when a video meeting on Zoom or Teams with six to eight people ends, everyone usually teleports to another meeting. In the real world, there is always an exchange of a few words between the participants. It is this informality that we recreate in the metaverse. And cognitive science has been working on this for a long time.

Virtual world, real fatigue

These video conferencing tools were first used widely following the Covid-19 crisis. The positive and negative consequences have been numerous. For example, cognitive sciences are closely studying Zoom-fatigue syndrome, the feeling of exhaustion that can be felt after making a large number of video calls. Apart from the fatigue, the brain also retains information less well than it does in face-to-face work, which in my view nothing can compete with. But in this new world that is emerging, we will undoubtedly travel less, and we will have to adapt. The metaverse is a solution for recreating presence, one’s own and that of others, thanks to virtual worlds. Finally, this metaverse produces ten times less greenhouse gases than traditional videoconferencing solutions. The reason is simple: all the images needed to create the environments in the metaverse are calculated locally, directly on the user’s machine. The only information that passes through the network, the heart of the production of greenhouse gas emissions, is therefore minimised. This gives the emerging metaverse other characteristics than advertising or NFTs.