Nuclear fusion, which is being explored in particular in the framework of the ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) project in Cadarache, is showing much promise. It is a scientific and technological challenge taking place over several decades. One of the most important challenges of fusion is to create and maintain plasma, a medium containing energetically charged particles, at 150 million degrees Celsius to sustain fusion reactions.

Plasma is considered as the “fourth state of matter” (after solid, liquid and gaseous states) and is sometimes described as a “soup of electrons and ions”. The plasma state is widespread in the universe. It can be observed, for example, in the aurora borealis or the ionosphere: the bombardment of particles from the solar wind where solar radiation rips electrons from atoms or molecules in the very high atmosphere, causing ionisation. The ionosphere is a diluted, partially ionised medium, in which the electrons can be quite energetic but in which the ions, atoms or molecules remain quite cold; the collective effects characteristic of plasmas are already at play there.

Another plasma with radically different conditions is that found at the heart of the sun or other stars: fully ionised matter reaches temperatures of the order of ten million degrees, which allows light elements, such as hydrogen, to fuse to form heavier atoms. The fusion process requires a lot of energy, and it produces even more. It is this process that we hope to reproduce when we talk about “fusion energy”.

ITER: an experimental reactor

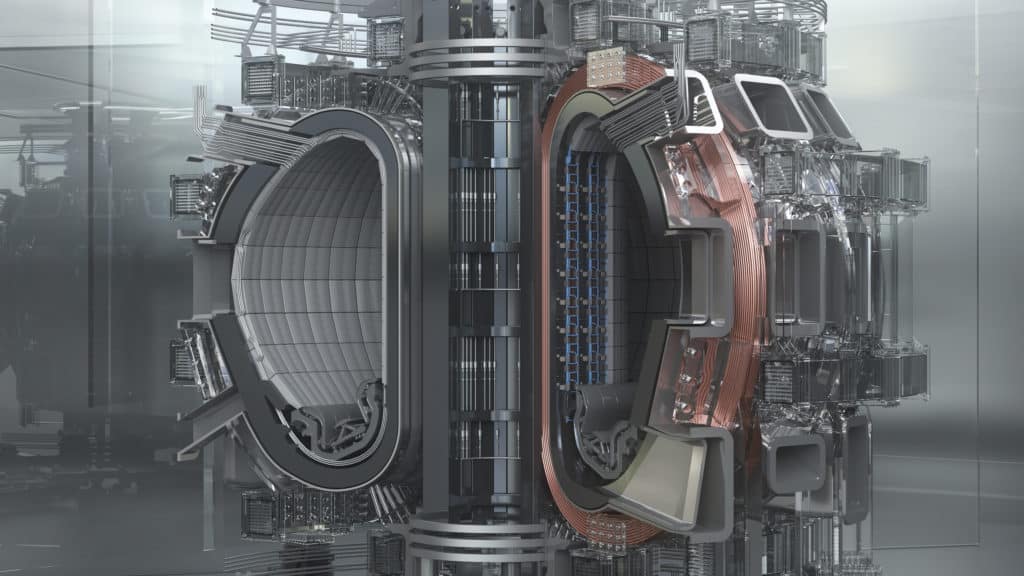

The ITER project involves experimenting with the production of energy by fusing the hydrogen isotopes (which have the same charge but different mass) deuterium and tritium to form helium. The device used is called a tokamak (the Russian acronym for “toroidal chamber with magnetic coils”!). Developed in the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s, it involves magnetically confining charged particles in the plasma.

ITER is an experimental reactor and it the result of an unprecedented international collaboration (34 countries). It is currently under construction in Cadarache, situated north of Marseille, and represents the demonstration stage of fusion after 50 years of research. The ITER core is a giant tokamak almost 30m high.

ITER, an experimental reactor resulting from an unprecedented international collaboration between 34 countries, is the demonstration stage of nuclear fusion from 50 years of research.

For fusion to occur, the nuclei must collide quickly enough to overcome their coulombic repulsion and often enough for the process to be self-sustaining. A tokamak must therefore maintain relatively high densities of light ions at enormous temperatures – around 100 million degrees – for a sufficiently long time.

In contrast to the fission of heavy atoms, where the products of the reaction themselves cause other reactions, there is no mediator of the fusion reaction and therefore no chain reaction. It is precisely the absence of the possibility of a runaway reaction in a fusion reactor that makes fusion much more attractive than fission. Moreover, fusion does not produce greenhouse gases, nor long-lived fissile or highly radioactive elements (although the materials inside the reactor are activated, they have short lives; the fuel for fusion is abundant – there is 33g per m3 of deuterium in water – and it can be easily extracted by electrolysis; tritium can be produced in the fusion reactor from lithium, which is abundant on Earth too).

Intense magnetic fields

As it is not possible to contain a plasma at thermonuclear conditions (150 million degrees) in an ordinary material container, intense magnetic fields (of the order of 5 to 10 T) are used to isolate the charged particles of the plasma from the chamber that holds them. The tokamak configuration, which is the best performing, combines three coil systems to generate a torus-shaped magnetic “cage” in which the charged particles circulate while remaining confined.

How can this plasma be heated to initiate fusion reactions? There are several options: heating by radiofrequency (put simply, by microwaves); heating by collisions, by injecting hydrogen ions carried at high energy in an accelerator; the question is how to neutralise these energetic ions so that they can enter the tokamak (if “nothing” exits, nothing goes in either).

How can the plasma be maintained at these very high temperatures so that the process is sustained? The plasma must above all remain “stable”: large-scale instabilities lead to plasma loss on the container walls, in the same way that the large arches that develop on the surface of the sun eject the matter that reaches us in the form of the solar wind. This is because instabilities and turbulence can develop in very hot plasma – a state of matter that is by definition not in thermodynamic equilibrium.

The large size of ITER comes from the fact that turbulent agitation increases collisional diffusion across the magnetic field lines: vortices of different sizes stir up the material and mix the hotter core with the colder edge. More insulating “layers” are needed to maintain the heat in the core of the plasma. We are working both to develop observational tools, under conditions never before experienced, to understand and model these phenomena and to optimise the control of turbulence.

Other containment techniques?

Nothing that can be done in your garage… contrary to what some far-fetched theories about fusion would have us believe. Other magnetic configurations exist, such as the “stellerator”, developed by the Max Planck Institute in Germany, to name just one.

The difference is mainly in the way the complex magnetic structure is produced (by field lines wound on nested cores): in the case of the stellerator, it is the coils, which are extremely complex in design, that generate the magnetic structure directly and “continuously”; in the case of the tokamak, it is the composition of the field produced by the coils and the field produced by a current, which will be maintained for about ten minutes in ITER and will therefore have to be cyclical.

It is difficult to predict the most efficient configuration in terms of containment quality, which is closely linked to the size of the device, and in terms of economic viability.

ITER: a very long-term project

Launched in the mid-1980s, the first plasmas will not be obtained before 2027. However, the entire community is working to progress on the scientific and technical issues that could make fusion energy available in the second half of the century. The European tokamak JET, the largest currently in operation, recently broke records for the fusion energy produced (59 MJ in a realistic deuterium-tritium target plasma). Very intense magnetic fields (20 T) have been obtained with tokamak-type coils using high-temperature superconductors, paving the way for smaller, more efficient and therefore more economical devices. An increasing number of these advances involve start-ups and private initiatives that undoubtedly signal the growing maturity of the field. ITER remains essential for the community because it is the only place where it will be possible to test all the problems linked to fusion energy production in an integrated way.