Considered by some as a potential solution to humanity’s future energy problems, controlling thermonuclear fusion has been the dream of researchers (and research laboratories) since the 1950s. Over the past 70 years, enormous progress has been made in mastering this energy source – the same processes by which all the stars in the universe are powered (including our Sun). As impressive as this progress is, it is clear that industrial applications of this research are still lacking. “Nuclear fusion is 30 years away… and has been for 50 years now,” we often hear. In recent years, however, the private sector has begun to show interest in the field. Where are these projects at? Here is a quick rundown.

Major international projects

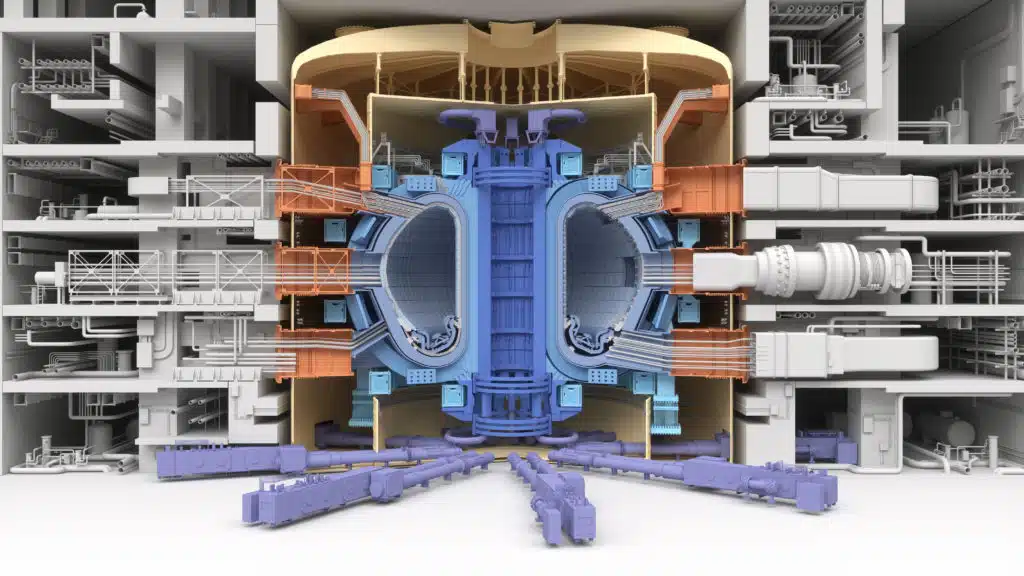

When one thinks of civilian energy production by thermonuclear fusion, the first project that comes to mind is ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor). This colossal scientific, technical and industrial project, currently under construction in Cadarache (France), is part of the 2nd generation of tokamak prototypes. The tokamak is a technology that allows a plasma (a “soup” of light atomic nuclei heated to at least several tens of millions of degrees) to be confined, using magnetic fields, in a vast toroidal casing in which nuclear fusion can take place.

The first generation of this type of reactor produced very interesting results in the 1990s. In 1997, the British experimental reactor JET (Joint European Torus) achieved both a record plasma temperature (of 320 million degrees) and a record amplification threshold (of η = 0.7). This means that for every 1,000 joules of input energy, 700 joules of fusion reactions are produced.

The objective is obviously to recover more energy from these reactions than was fed into them (η > 1). In absolute terms, if we consider the various losses and technical limitations at all stages of the process, a production yield of at least 10 (i.e. recovering 10 times more energy than that injected) would have to be achieved to start industrial production for this type of reactor. However, this efficiency depends (among other things) on the volume of the reactor. This is why ITER, an international project resulting from the collaboration of 35 countries, will be much larger than JET (the vacuum chamber will be 6.20 m wide and 6.80 m high for a plasma volume of 840 m3). Its objective is not – and it is important to remember this – to produce energy industrially but rather to prove that an efficiency of 10 can be achieved.

The toroidal tokamak principle is not the only possible design for a so-called nuclear fusion “magnetic confinement reactor”. Other configurations are also being studied and are producing very interesting results. In Germany, another avenue is being explored: the Wendelstein 7‑X stellarator. The principle of the stellarator is still to confine the burning plasma by means of an intense magnetic field. These systems are much more complex to build (requiring deformed magnetic field coils) but much simpler to use once the plasma has been confined.

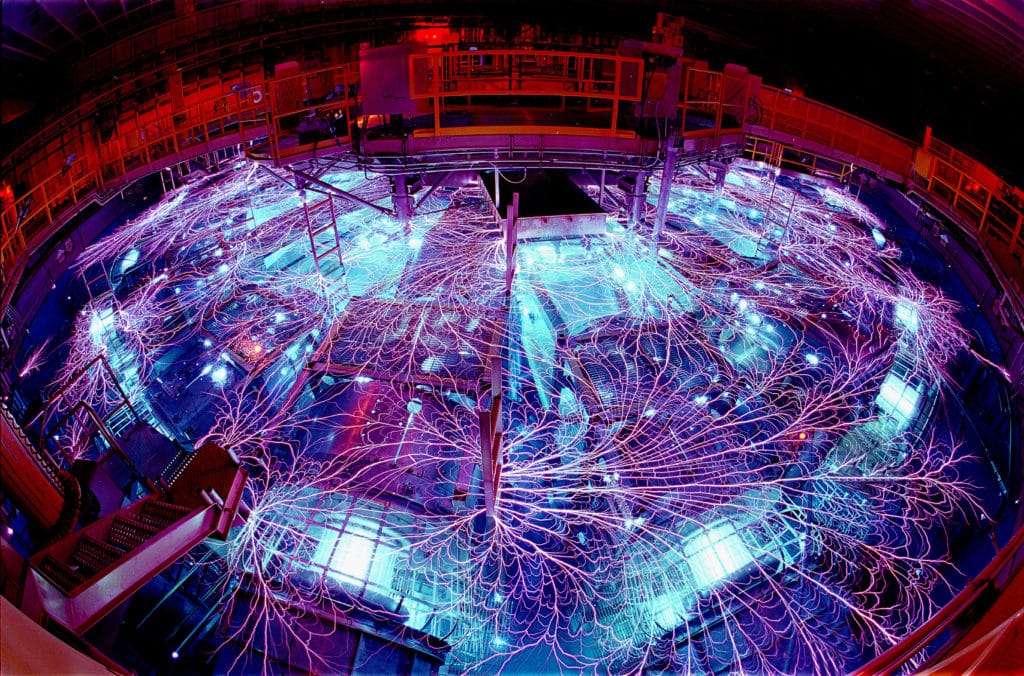

Another important route to nuclear fusion is being explored: inertial confinement. Here, instead of a magnetic field to contain the plasma, pulses (electric or laser) are used to compress a ball of fuel to pressures and temperatures that allow nuclear reactions to be initiated. Unlike magnetic confinement, which uses low-density plasmas but very long reaction times (currently of the order of a minute), inertial confinement works on the opposite principle: obtaining extremely high densities during very short times (of the order of a nanosecond or even less).

Small private projects

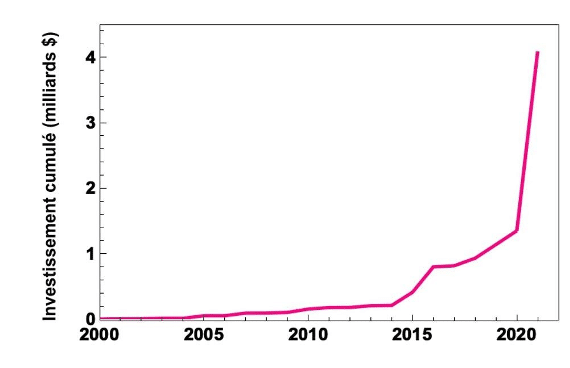

Since 2015, the private sector has also become very interested (and increasingly so) in the field of controlled nuclear fusion for several reasons. The first is climate change. Indeed, nuclear fusion is a “decarbonised” energy. The fusion of two hydrogen isotopes (deuterium and tritium) produces helium, a reaction that does not generate any combustion or CO2 emissions. It is therefore a climate-friendly. The other reason is technological. The ITER project promises clean energy production, something that private projects are banking on. In addition, new materials and technologies (superconducting tapes, lasers, calculation algorithms, etc.) allows for small experimental reactors at lower cost. Finally, of course, the promise of a risky investment, but extremely profitable if successful, attracts investors and companies, often backed up by investment funds, benefactors (Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos) and some public funding.

There are now more than 30 privately held merger companies in the world, according to an October survey by the Fusion Industry Association (FIA) in Washington, DC, which represents companies in the sector. The 18 companies, reporting funding, say they have attracted more than $2.4bn in total – almost entirely from private investment.

In the absence of research teams as important as those involved in public projects, size often needs to be replaced with smarts, and novel techniques need to be tried out. Again, this is a high-risk tactic, but the rewards can be extremely high if successful. Here, we can cite General Fusion with its concept of a piston-covered sphere into which a deuterium-tritium mixture is injected before the pistons produce a shock wave that compresses the plasma and produces the pressure and temperature conditions necessary for fusion.

Another company, CFS (Commonweath Fusion Systems) is relying on the development of new high-temperature superconducting magnets to build SPARC, a compact tokamak with an expected efficiency of up to 2. CFS announced in September 2021 that their new super high temperature magnet had reached an intensity of 20 Teslas. Construction is expected to be completed in 2025. Finally, Helion Energy, rather than seeking to produce electricity by turning turbines using the heat generated by the reaction at the heart of a tokamak, is proposing to produce this electricity directly by induction in electrical coils that surround the reactor.

Finally, First Light Fusion is a company that came out of Oxford University in the UK. It is pursuing a different strategy: the inertial confinement discussed above. Here, the fusion plasma is not held by magnetic fields. Instead, a shock wave compresses it to the immense densities needed for fusion. But at First Light, the compression shock wave is not created by energy-hungry lasers, but by using an electromagnetic pistol that fires a projectile into a target containing the hydrogen isotopes. The company is keeping the details of the process secret, but said that to achieve fusion, it will have to fire this projectile at 50km per second – twice as fast as is typically applied in current shock wave experiments.

Will these private companies, which are venturing into one of the most advanced areas of science and technology, succeed where the largest international collaborations are advancing only in baby steps? Nothing is less certain, but the next few decades are sure to be very interesting.