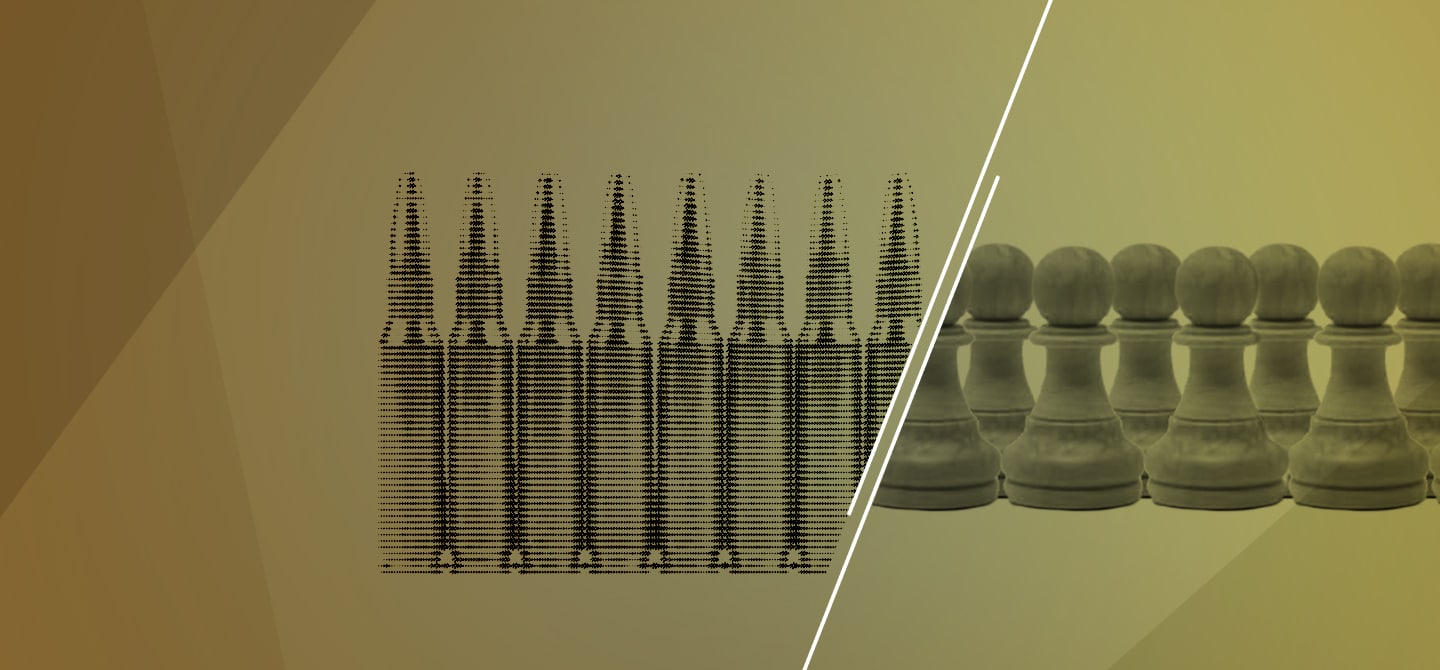

Asymmetrical warfare pits a state and its conventional forces against non-state entities: guerrilla fighters, terrorists, criminals and drug traffickers. Some of these entities act on their own behalf, while others act on behalf of other states in what is known as surrogate warfare.

Is asymmetrical warfare replacing war?

Military strategy has long been interested in divided groups; the Spanish against Napoleon’s armies, resistance fighters during World War II, or Chinese communists in the late 1940s, who were able to defeat forces which were, on paper, much more powerful than they.

This ‘asymmetrical’ warfare, which for a long time was the exception, is now becoming the norm. In a speech at the French Institute of International Relations in 2007, General Bernard Thorette, former Chief of Staff of the French Army, explained: « Large, conventional, head-on battles have given way to multiple, repeated engagements on a lower scale… this does not mean however mean low intensity. Our armed forces are now faced with fragmented, even atomised, states and societies, and with a complex ramification, that encourage the emergence of small, determined groups. The result is an almost systematic asymmetry of threats. These threats are not necessarily primitive, far from it, as shown by the widespread use of IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) in stabilisation operations.”

Our armed forces are now faced with fragmented, even atomised, states and societies.

Nearly fifteen years later, this observation takes on even greater significance, both for what it says about the asymmetry of threats and technological advancement of forces involved.

From low-tech to high-tech

Actors in asymmetrical warfare have been quick to understand the advantages of technology to renew their repertoire of action. Lines of code and the art of transforming civilian technological objects into weapons have now joined the Kalashnikovs and plastic explosives. Improvised explosives using mobile phones have been replaced by real innovations, combining high-tech civilian objects to make formidable weapons that are, for example, effective on a far greater scale.

A smartphone and a hundred small recreational drones can create a swarm of drones, whose coordinated attack is capable of causing panic on a battlefield and even more so amongst civilians. Hackers can, like the pirates of the past, put themselves at the service of a state and constitute an auxiliary force capable of carrying out offensives against physical or software infrastructures, causing serious damage.

Information wars are destabilisation operations carried out through highly decentralised networks, conducting attacks that leverage tensions within target societies. Here again, the results can be massive: the part played by Russian intelligence in Trump’s election in 2016 is a reminder of the relevance of Clausewitz’s argument that: “war is a continuation of politics, by other means”. Both on the battlefield and far from operations, technology gives unconventional modes of action, and the actors that wield them, unprecedented power.

This technological revolution is not without consequences in the art of war. It modifies the theatre of operations and further blurs the idea of the “front line” by allowing remote interventions. It also changes the profile of the players. Finally, it has led to an evolution in conventional forces, which are taking note of these new threats and learning how to counter them. In March 2021, Israel used swarms of drones coordinated by an AI for the first time. The United States has been talking about this since 2015.

Guerrillas acting like start-ups

Mobile, agile, inventive, these entities have points in common with pirates, but also with digital start-ups: their organisation is flexible, often decentralised, and they can mobilise a ‘base’ of people who compensate for their low critical mass.

Richard Taber, the main modern theorist of guerrilla warfare, speaks of a “war of the flea” (The War of the Flea: Guerilla Warfare, Theory and Practice, London, Paladin, 1977). In the tradition of Clausewitz, he insists on the political dimension of this form of warfare in the modern age, conducted by soldiers who are also militants of a cause (national sovereignty in partisan warfare, communist revolution, etc.). He gives a now classic definition: “guerrilla warfare has the political objective of overthrowing a contested authority, by means of small, highly mobile military means using the element of surprise and with a strong capacity for concentration and dispersion”. What strikes a reader in 2021 is that in every detail this definition applies to the strategies followed by digital entrepreneurs.

The digital age is one of the disruption of established powers by small, agile players.

The digital age is the age of the disruption of established powers by small, agile players, such as Airbnb in the face of the hotel sector or Uber in the face of the powerful corporations that protect the taxi industry. Appearing out of nowhere, they practice unconventional strategies and choose to move the theatre of operations to new spaces where they can concentrate their forces. As for the “dispersion” mentioned by Richard Taber, the network structure, the absence of a proprietary fleet or real estate, in short, the absence of a conventional “army”, is precisely the key to their success. They rely on a multitude of amateurs, not on an organised and trained contingent.

A cause and capital

They even have causes (sharing, sustainable development, social inclusion) to enlist these amateurs, which are admittedly less mobilising and less directly connected to their action than those of yesterday’s communists or today’s jihadists. However, the vocation to change the world, or at least to “disrupt” it, is an obligatory part of the pitch to investors.

Successful small digital players rely on the power of capital to concentrate their forces and move forward quickly. The notion of power is therefore not alien to their strategy or their success. The same is true of today’s guerrillas, who rely on private funds or foreign powers to carry out their actions.

The world of hackers provides a link between the two worlds, that of the guerrillas and of the start-ups. However, it is above all through a form of reciprocal inspiration that these two worlds communicate. The strategies of business and war have often crossed their models. Once again, it seems that we are witnessing cross-fertilisation.

Private funds and state power

In the 2016 case of Russian interference, 12 out of 13 people being prosecuted by the US justice system worked for the Russian company Internet Research Agency, which is itself being prosecuted. Specialised in influence operations on social networks, it has several hundred employees whose main task is to massively disseminate false information or messages in favour of the Russian government or in line with its domestic or foreign policy. However, it is not officially dependent on the Russian state. According to the US indictment, the Internet Research Agency is financed by Evgeny Prigogine, a businessman close to the Russian president.