If cancers manage to develop in a patient, it is because of the ability of tumours to both grow quickly and to manipulate the immune system. Tumours can weaken the immune response and, as such, drugs targeting and ‘waking up’ the immune system – such as the immunotherapies known as anti-CTLA4, anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 – have rapidly become treatments of choice for cancer patients1. Their effectiveness has resulted in more long-term remissions than before and, while great progress in cancer treatments have been made thanks to advances in biology, the opposite is also true. To better understand how this works, findings from clinical research into immunotherapies is helping scientists in fundamental research to know where to look.

Waking up the immune system

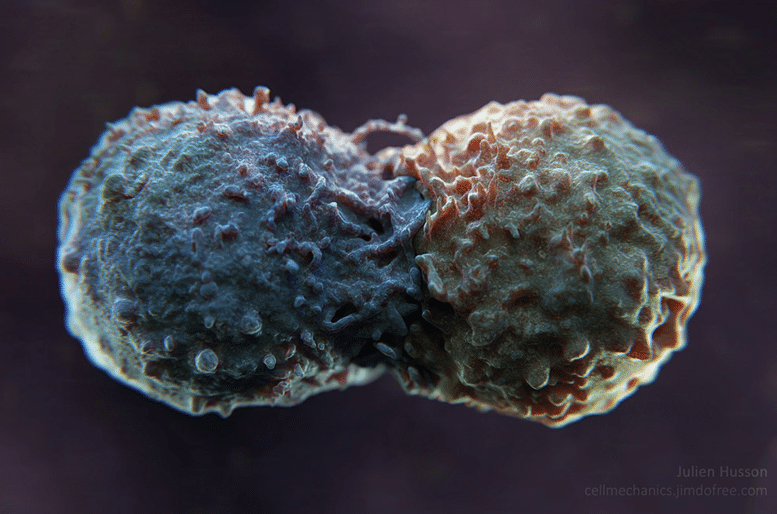

Biophysicist Julien Husson, a researcher at the Laboratoire d’hydrodynamique (LadHyX) at the Institut Polytechnique de Paris, is a good example of this type of work of. “My aim is to model the way in which a tumour cell and the cells of the immune system interact,” he says. Notably, he is trying to understand a fundamental and crucial aspect of immunotherapy; the way the treatments manage to re-awaken T cells – the cells of the immune system that are normally suppressed by cancer. In other words he is trying to understand, “how immunotherapies block the immunosuppressive effect of tumours and reactivate T lymphocytes.”

The key to this interaction is known to be an antibody, PD-L1, found on the surface of tumour cells, which binds to T cells that pass close by the tumour. When it comes into contact with the PD‑1 receptor of these immune cells, it inhibits their activity, like a control switch. The T cells are switched off, unable to direct their weapons at the abnormal cell. To prevent tumours hi-jacking patients’ immune cells in this way, immunotherapies are designed to block this inhibition. As such, patients are given small anti-PD-L1 molecules, which bind specifically to the tumour cell’s PD-L1 antibody and thus prevent it from turning off the T cells. This inhibition of inhibition wakes up the immune system – or rather prevents it from being blocked. But to understand more about how this happens, researchers are seeking to first understand how the tumour antibody acts on the T cell in detail.

Observing cells closely

To study this effect, Julien Husson attached PD-L1 antibodies onto glass beads as simplified models of tumour cells and filmed the reaction of an immune cell to it using an electron microscope. “We found that when T cells come into contact with an antibody, it produces huge protrusions,” says Julien Husson, who was the first to observe a real ‘kiss’ between a lymphocyte (T cell) and a tumour (you can watch the video below, or here).

“But when this antibody is PD-L1, the protrusions become more rigid,” he says. He observes changes in shape these cellular protrusions, their structure appears less mobile under the microscope. Julien Husson therefore assumes that, under normal circumstances, when the tumour and T cell come into contact, it results in a remodelling of the cytoskeleton (the internal structure of the T cell). This profound modification of the immune cell seems to allow it to mobilise its cytotoxic system to attack the abnormal cell, i.e. the tumour. But when the tumour releases PD-L1, the remodelling seems different and serves to block this immune activation; meaning the immune cell cannot attack the tumour.

To confirm his hypothesis, Julien Husson is preparing to reproduce this experiment by replacing the glass beads with cells from real patients thanks to a collaboration with Claire Hivros of the Institut Curie. This work could help doctors understand why some patients do not respond to immunotherapy. “This experiment involves extremely precise physical manipulations and involves working on a real medical problem,” explains the researcher from the Institut Polytechnique de Paris. It is part of an increasingly multi-disciplinary approach that is fuelled by interactions between clinical and fundamental research. “It’s a long chain of events. In a few years’ time, our work could perhaps be used to improve the therapeutic strategies offered to patients,” explains Julien Husson. But initially he hopes to shed light on the functioning of T lymphocytes.

For more information

Science Signaling, 2020; 13(627), eaaw8214. Diacylglycerol kinase z regulates actin cytoskeleton remodeling and mechanical forces at the B cell immune synapse. Sara V. Merino-Cortes, Sofia R. Gardeta, Sara Roman-Garcia, Ana Martínez-Riaño, Judith Pineau, Rosa Liebana, Isabel Merida, Ana-Maria Lennon Dumenil, Paolo Pierobon, Julien Husson, Balbino Alarcon, and Yolanda R. Carrasco.