Youth unemployment rate is defined as the percentage of 15–24 year-olds capable and educated to work (a.k.a. the youth labour force) who are unemployed. On a global scale, this affects as many as 75 million young people who are trained but remain out of work1 (compared to 621 million for “NEETS”), with varying proportions depending on the country. As such, particularly in developed economies, the youth labour market is one of the key indicators of a healthy economic system; not to mention the important social repercussions.

In liberal market economies like the UK or USA, when there is pressure on financial markets such as the Covid or 2008 financial crises, it is the youngest who are laid off first. And in those countries, there are also less apprenticeship places during these periods, so the younger generation struggle to find early-stage career work. Hence, there is a clear social function of the education system in integrating youth into the middle market. That’s why the efforts of other countries like Austria and Germany to keep up apprenticeship places during crises have proven beneficial to maintaining a lower youth unemployment rate.

The education-employment relationship

To better understand the factors involved, over the years there has been much research into the relationship between education and the employment. A relevant model that was created by Busemeyer in Trampusch2 over a decade ago used a 4‑fold typology to describe the link between education and the labour market. Their model essentially distinguished between the commitment of the state towards education and training, whilst considering contributions from private companies. These can either be low or high, so essentially leading to four types of skills regimes; for example, if contribution of both is low, we can speak of “liberal” systems like the UK and USA. High state input and low private contributions include countries like France and Sweden, or inversely low state commitments with high input from companies are seen in Japan. Whereas in Austria, Germany, Denmark and Switzerland which can be considered as “collective skills regimes” commitments are high on both sides.

Although, this analysis didn’t necessarily compare whether one or other system was better, it did provide a classification of how vocational education and training and its relation to industries differs across countries.

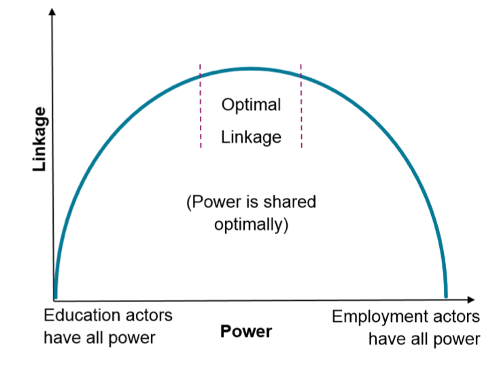

Another way of looking at the education-employment linkage is to assume an optimal equilibrium between the two and hence a shared input from both public education systems and private entities (fig. 1).

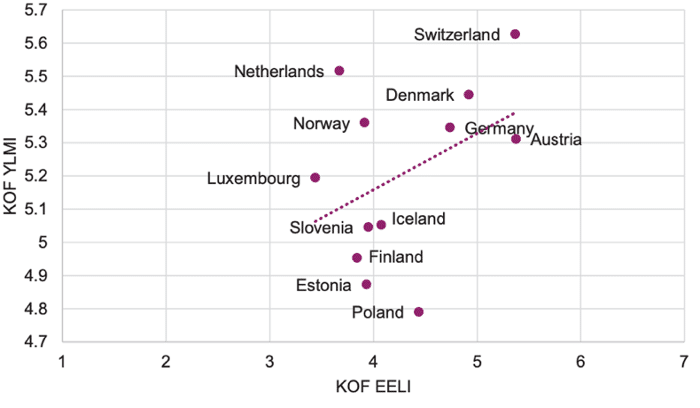

This approach has been tested by researchers at the KOF Swiss Economic Institute of the ETH Zurich by developing the so-called education-employment-linkage (EEL) index. They looked at the most prominent vocational education programmes in OECD countries and asked experts and stakeholders about this link via surveys. For instance, they asked about the extent to which employers contribute to the design of curricula or to skills assessment. Using that they came up with an index based on qualitative criteria that they weighted to generate a quantitative index.

Using the EEL index, it is therefore possible to rank countries according to how close the cooperation between education and employment is. In a way, this also proves the skills regimes approach, because collective skills regimes (such as Austria or Germany) turned out to rank high on the EEL index. However, the Swiss researcher could draw more in-depth conclusions. As such, they noted a correlation between EEL index (KOF EELI) and youth unemployment rate – countries that scored better were those with less youth unemployment (KOF YLMI).

But let’s remain prudent. Even though we have good arguments to believe there is a causal link, we don’t yet have the proof beyond correlations. Also, this sort of research is usually carried out in these one-off studies, like snapshots of certain industries in certain countries at certain points in time. We can compare countries, but for example we only have the EEL index for the year 2016 and there isn’t a comparable index for other years – so it would be interesting to have a longer time series.

Education, employment, and quality of life

Going beyond the current analysis, this then begs the next question: if there is a strong link between education and employment, can we improve society as a whole? Even though youth unemployment rates can be a marker of economic health, the current models don’t factor in for other larger societal indicators; like work-life balance, quality of life, or general happiness. We are still far away from having a comprehensive model of these relationships.

Furthermore, a higher commitment education scheme appears to be better but only in certain aspects that we are looking at. Yes, more young people find jobs but once you start looking at other economic indicators such as productivity and innovation, there impact of a close education-employment-linkage is less clear. Also, in terms of labour market trends, predictions are becoming less and less successful in knowing what skills are needed to the point where much of what we hear is political rhetoric; we have no scientific evidence in which route we should go. It is therefore understandable that key skills such as numeracy and literacy, which can be considered universal, are emphasised. Of course, issues like problem solving, creativity, and teamwork – considered “21st Century” skills – are also crucial but these are less transferrable across different professional domains.

Reorganising work

All in all, we mustn’t forget that the way work is organised is in the hands of companies who employ people. This is the main leverage I would say. You can try to change and improve the education system as much as you want but if there is not the right sort of jobs proposed by employers then it won’t have a positive effect on employment rate. Hence, job design and job quality are key!

Let’s take two extreme cases. On one spectrum, we are seeing a tendency for companies to organise work in a way that can be done by anybody. This includes micro-work such as that traded by Amazon Mechanical Turk. Here, tasks are divided into such tiny pieces, like clicking on an image on a screen or scanning a product on a shelf, that no or little training is required. However, there is a danger here that these methods be used as elaborate ways of human exploitation.

On other hand, after recovery from the COVID crisis, in some countries in Europe, the labour market is already back at rates from before the crisis. Some even have lower unemployment rates than before. The pandemic made many people consider what they consider a quality job, and the new generation of graduates are demanding much more from employers than they did 20–30 years ago. It is putting pressure on businesses pushing them to think about how to change work. In my view the “Great Resignation” is not a singular phenomenon of the COVID crisis, but the herald of a changing labour market. As such, in years to come we will need to see a difference in work-organisation to make jobs more attractive.

A question that remains, however, is what role will the state play in where we are headed?

Further reading

- http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~iversen/PDFfiles/Busemeyer%26Iversen2011.pdf

- http://hozekf.oerp.ir/sites/hozekf.oerp.ir/files/kar_fanavari/manabe%20book/TVET/The%20Wiley%20handbook%20of%20vocational%20education%20and%20training.pdf#page=157

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299395981_Success_factors_for_the_Dual_VET_System_Possibilities_for_Know-how-Transfer