To reach the Moon, then Mars and stay there for long periods of time, astronauts will need to either take resources with them or have them transported to them from Earth or lunar orbit. Nevertheless, however, they will still need to be able to process resources found on the ground to meet their needs. How will these resources be extracted and processed? In Situ Resource Utilisation (ISRU) programmes are designed to find ways to best answer the question.

Why will we need to exploit resources in space, and how can it be done?

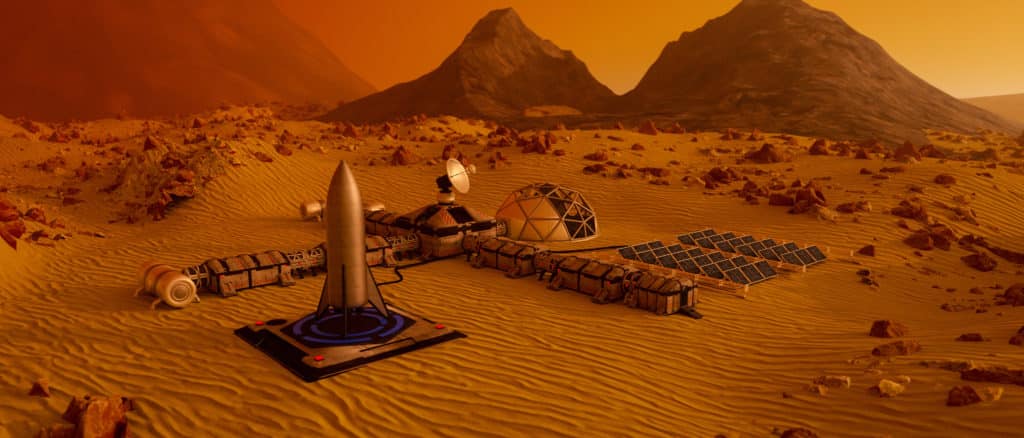

Gerald Sanders. For long-duration space exploration missions to the Moon or Mars, astronauts will need to find or produce the resources they need to breathe, shelter, or feed themselves, travel and conduct their missions. As such, being able to use ‘local’ resources such as water, carbon or oxygen during these missions will reduce the mass to be launched from Earth – a factor that has a direct impact on the cost of missions. For every kilogram that lands on Mars, between 7.5 and 11 kilograms will have to be launched into Earth orbit. And to reach Mars, millions of tonnes of propellants, i.e. rocket fuel, will be needed, equivalent to the payload of several super-launchers. Moreover, fuel will also have to be produced on site if the astronauts are going to have a good chance of returning to Earth. It’s not just about going to Mars, it’s also about coming back.

The aim of the In-Situ Resource Utilisation (ISRU) programme at NASA is to develop techniques for locating, extracting, processing and exploiting local resources, ores and chemical components required for exploration missions. In concrete terms, we will need to have means of locomotion, extraction infrastructures, energy production, processing and storage of products, manufacture of machines and tools, communication, maintenance, etc., just as we do on Earth but in extreme conditions of temperature, dust, and absence of atmosphere. That being said, the question of producing in space is not a new idea. I read a technical article on how to produce oxygen from lunar soil, which was written by an engineer in 1961, i.e. before man had even been to the Moon!

What resources could potentially be used?

Firstly, natural resources: water, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, silicon, carbon or rocks, particularly regolith on the Moon or Mars. All these resources will be used for life support of astronauts, for the production of fuels, photovoltaic cells or construction materials, among others. At present, developments are focused on the production of oxygen and fuel, particularly methane or hydrogen. But resources also include all the waste that has to be destroyed or transformed, and spare parts. You have to be able to repair a system without waiting for the next delivery to bring back the missing part. The problems to be solved are very different depending on whether the mission takes place on the Moon or on Mars. It takes three days to get to or from the Moon, whereas the trip to Mars takes between six and eight months, and the optimal launch window from Earth, only occurs every 26 months – when the two planets are closest.

What are the main challenges?

There are four. The first is to understand what resources are available locally and to know them well. Thanks to the missions that have been carried out so far, we already have a good knowledge base of the resources on the Moon, and we are collecting ever more information about those on Mars. Then, there is the challenge of exploiting these resources. We have known how to mine on Earth for centuries, but what equipment will enable us to mine on Mars and process the ores? How will we power them? How will they be maintained? These are all questions that we need to answer now.

This brings us to the third challenge, that of the environment. There is a lot of radiation on Mars and less gravity, so we have to rethink how to do things. We are studying in the Arctic, in the desert or at the bottom of the ocean to find relatively similar conditions, but they are still very different from what we will find on Mars. The fourth challenge is reliability, which must be total for manned space flight. When they come back to Earth, astronauts must be sure that they have the right fuel, that they land in the right place etc. In short, we must define the best strategy. On top of that, there is a fifth challenge, which is more political than technical: definition of a space treaty and adherence to it by all the stakeholders involved.

Will technological progress enable us to meet these challenges?

We are building on the technologies we know on Earth, and we are trying to turn the characteristics of the space environment to our advantage. For example, we could exploit the vacuum on the Moon to conduct experiments that are difficult to do on Earth. We are not looking for perfection, but for efficiency and a good return on investment. We are also looking for lessons that can be used on Earth. How to produce fuel, eliminate maintenance or design lighter equipment could help reduce our carbon footprint.

Why not just send robots, as this would reduce the need for water and oxygen?

Our approach is not humans versus robots, but both together. While robots are extremely useful, there are things humans can do and understand that robots cannot. The first SpaceX tourist flight to the Moon will carry a Japanese collector and eight members of the public, including artists, who will report on their experience. I’ve talked to astronauts and geologists from the Apollo missions. They have an immediate understanding of the geology of what they see, they understand instantly what has happened, they know where to take samples. Whereas a robot needs a long learning curve to understand. Not to mention the latency of communications between Earth and Mars, which makes remote control difficult.