How AI is emerging as a teammate for mathematicians

- AI models produce reasoning comparable to that of a first-year PhD student not yet exceeding the level of human mathematicians.

- Numerous obstacles in AI methods still hinder research in fields with limited data.

- Although, without providing complete solutions, AI can serve as an assistant in several different fields.

- For example, Math_inc's Gauss formalised the Strong Prime Number Theorem (PNT) in Lean, with 25,000 lines of code and over 1,000 theorems and definitions.

- In the short term, researchers will use platforms to generate and verify proofs, while in the long term, systems could combine automatic generation and formal verification

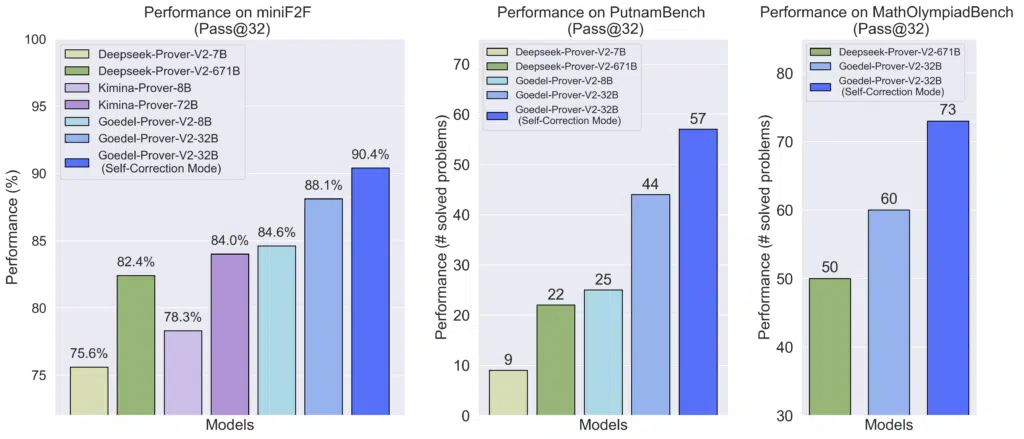

Recent advances in automated reasoning have placed artificial intelligence at the heart of new studies in mathematics. Systems such as Goedel-Prover, designed to generate and validate formal proofs, showed significant progress in 2025, achieving high levels of performance on specialised test sets1. At the same time, APOLLO highlighted the ability of a model to collaborate with the Lean proof assistant to produce verifiable demonstrations, while automatically revising certain erroneous steps2.

The challenges associated with these advances were examined at the AI and Mathematics conference organised in April 2025 by Hi! PARIS, which highlighted the growing role of formal verification in current research3. This work is consistent with certain analyses published in the scientific press. In 2024, Le Monde highlighted the potential of these tools to accelerate the production of results, referring to the extensive use of models to explore avenues that are difficult to access using traditional approaches4. For its part, Science & Vie reported in 2025 that certain systems had achieved high scores in Olympiad-type competitions, demonstrating their ability to deal with structured problems5, even if these scenarios only partially reflect the requirements of mathematical research.

To define these dynamics while separating fact from fiction, Amaury Hayat, professor at École des Ponts ParisTech (IP Paris) and researcher in applied mathematics and artificial intelligence, shares his expertise. He heads the DESCARTES project, dedicated to learning methods in contexts where data is scarce, as well as several projects on reinforcement learning applied to automatic proof. His analyses examine current developments in automated reasoning in mathematics, drawing on published data, tools and results.

#1 AI can solve all open mathematical research problems without human intervention: FALSE

Amaury Hayat. Artificial intelligence, particularly models capable of reasoning in natural or formal language, can already produce evidence at the level of a first-year PhD student in certain cases. There are simple situations that it cannot yet handle, but there are also complex problems that it can solve.

We do not yet have systems capable of generating, from start to finish, proofs that surpass the level of human mathematicians. However, AI can already provide very interesting proofs and, in some cases, solve problems that have remained unsolved for a long time. In these cases, they often exploit fragments of solutions scattered across different articles or fields, which AI is able to combine effectively thanks to its ability to access and organise the knowledge available on the internet. For example (Figure 1), GoedelProver-v2, a formal model, was trained on 1.64 million formalised statements and, in 2025, achieved an accuracy of 88.1% without self-correction and 90.4% with self-correction on the MiniF2F benchmark6.

#2 The scarcity of formalised data significantly hinders the training of AI models: TRUE

The main obstacles are more related to AI methods than to mathematics itself. In highly specialised fields of research, data is extremely limited. However, with current AI training methods, this scarcity is a major obstacle. Reinforcement learning can theoretically overcome this problem, but it still requires a significant number of examples to be effective and is particularly relevant when automatic verification is possible.

Today, this verification can be done either in natural language, which limits the types of problems that can be addressed, or in formal language, where a computer can directly confirm whether a proof is correct. The challenge is that current AI systems that express themselves in formal language are not yet at the level of AI systems that express themselves in natural language.

Two avenues are being explored to make progress: increasing the amount of data by automatically translating natural language into formal language and improving reinforcement learning methods. This approach combines the power of natural language models with the rigour of formal verification, providing automatic feedback for trial-and-error training.

Godel-Prover is interesting because it quickly achieved the performance of our model on the PutnamBench dataset, initially obtained with a very limited number of examples. Subsequent versions, as well as DeepSeek-Prover, are extremely powerful, particularly for Olympiad-type exercises.

Our objective with DESCARTES is different: we are targeting research-level problems, characterised by a low data regime. The challenge is therefore to develop models capable of working under these conditions, unlike traditional methods that exploit very large quantities of examples.

#3 AI can serve as an effective assistant in scientific collaboration: TRUE

For most of the problems I test, even the best models do not provide a complete solution. However, AI does provide interesting answers on a fairly regular basis. Although it is not as reliable as consulting an expert colleague, the advantage is that you get a single interface capable of handling multiple domains simultaneously, which saves a lot of time. Sometimes, it is almost like having a highly experienced colleague on hand to assess what is feasible. For example, Math_inc’s Gauss formalised the Strong Prime Number Theorem (PNT) in Lean, producing approximately 25,000 lines of code and over 1,000 theorems and definitions7, while Prover Agent uses a feedback loop to generate auxiliary lemmas and complete proofs8. These models significantly reduce the time spent on exploration and verification, while enhancing the rigour of the results.

#4 Advanced computing systems truly understand mathematical reasoning when they produce proofs: FALSE

For the DESCARTES project, we work directly in formal language, which allows the computer to verify the correctness of proofs. However, when I use traditional LLMs for mathematical articles outside of this project, I have to read and verify the proofs manually. This saves a lot of time, but there is still a risk: the errors produced by the models are sometimes surprising, unexpected, and do not correspond to those that a human would make. They can sometimes appear very credible while being false, which requires particular vigilance.

#5 AI risks completely replacing mathematics education: FALSE

There are two distinct levels in mathematics education: training up to master’s level and post-master’s research. When it comes to learning the basics and understanding proofs, AI’s ability to prove theorems does not fundamentally challenge traditional teaching methods. Human training in reproducing proofs remains essential for developing reasoning skills.

On the other hand, in research projects or examinations where students have access to all resources, AI can play the role of a personal assistant. For example, in a Master’s project, it could help produce evidence on open problems, enriching the learning experience and creativity of students.

#6 Some advanced digital systems can generate almost-complete scientific articles, but their reliability remains variable: UNCERTAIN

In the short term, researchers will use platforms such as ChatGPT, Gemini or Mistral to generate and verify evidence quickly, saving considerable time. Specialised tools are also beginning to emerge, such as Google Labs for exploring Google Scholar or Alpha Evolve for constructing mathematical structures, while Gemini‑3, Deep Think and GPT-5-pro (language models) first generate a draft and then use verification tools to identify any errors, based on the available information.

In the medium to long term, systems could combine automatic generation and formal verification, accelerating research and influencing publication patterns and academic expectations. Current models are already capable of producing nearly complete articles based on previous publications, which could transform the production of ‘incremental’ articles and free up time for more ambitious research. For example, comparative tests show that on the miniF2F benchmark, APOLLO achieves 75% success for automatically generated proofs, while Goedel-Prover achieves 57.6%9. However, some models can produce subtle conceptual errors or repetitive passages, making human supervision essential to validate scientific reliability.

Certain aspects of researchers’ careers will certainly need to be rethought, including the publication system, peer review and article writing. Models are now capable of producing high-quality proofs and articles, and this could change the nature and frequency of scientific publications.