*The following contribution has been developed in greater detail in an academic publication by Benghozi and Simon (2025)1

Alongside the fast-growing video games industry2, a brand new autonomous and powerful segment of the market has emerged with quite different structure: esports. A contraction of “electronic” and “sports”, it combines competitive video game play in front of an online audience with the addition of face-to-face spectators. The market value of esports generated $2,396.9m in revenue in 20243, with an audience expected to reach 640.8 million by 20254,5.

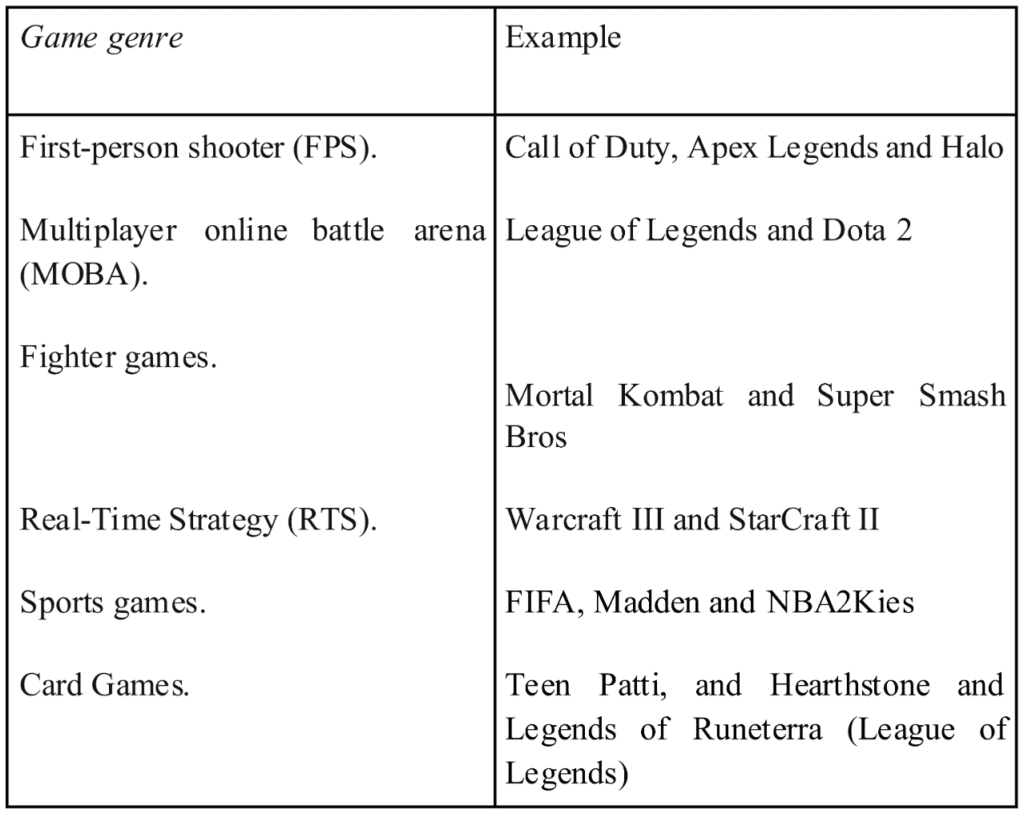

Esports are spread over most of the usual video games genres (see Tab. 1) and rely on key components including: interconnectivity (Internet over broadband freed from physical venues); online games on consoles, PCs and mobile; relevant infrastructures to host gamers; and a mass audience6. The esports ecosystem is organised through professional or semi-professional competitive gaming within an established structure (tournament or league) with a specific goal, such as championship title or prize money.

In terms of the global landscape, esports share the features of the video games industry as a whole7, namely a strong dominance of Asia: South Korea first licensed professional players in 2000 and well over half of esports views (57%) come from the Asia Pacific region8. Europe accounted for 16% of views, and North America 12%.

Converging value chains

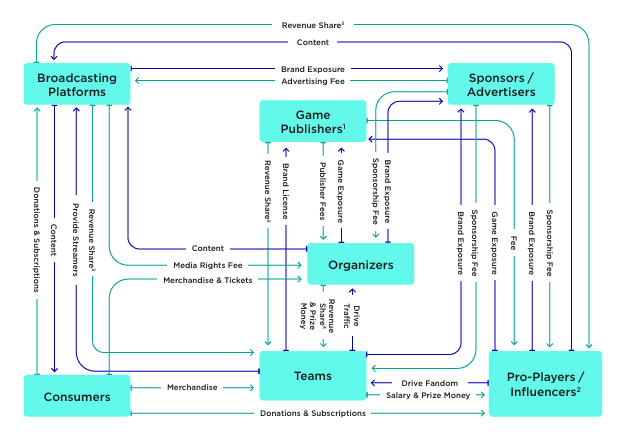

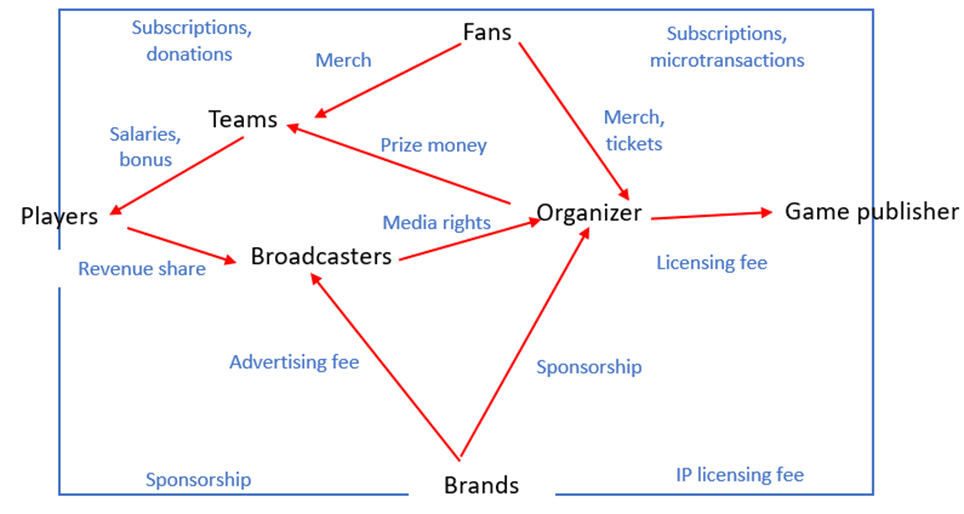

Esport coalesces two lines of business: video games on the one hand, and sporting events on the other. This results in a landscape (Fig. 1) made of developers, game publishers, leagues and tournament organisers, content distributors (streaming companies, OTT and broadcasters), teams, software and hardware providers. Like all cultural industries, the sector is marked by a fringe oligopoly: powerful dominant players revolve around a myriad of smaller, independent players.

Developers

Developers – studios with multidisciplinary teams – design the game and elaborate the necessary software to run it. Most companies are small and numerous. They specialise in certain types of games, may target a specific device or develop for a variety of platforms. Since the production of video games is made of high fixed costs, the developers need early investments. They must often lean on publishers as pre-financers.

Publishers

The publishers manufacture video games, license the property rights and the concept of the game, handle the marketing and often act as distributors and retailers. They develop games internally or order them from developers. Publishers own the intellectual property of the video games which esports leagues, clubs and players compete in. Major publishers fund esports teams or sponsor tournaments. They can own multiple games and be organisers of the games they operate themselves. Generating the deal-flow, managing large budgets, developing global branding, and organising marketing and property rights give publishers a strong position. Consequently, in most esports, the developers and publishers depend on the same company; for example, Blizzard Activision or Tencent retain their own studios.

Content distribution: broadcasting and streaming platforms

To stream and propose the viewing of game tournaments, content distribution companies pay the publishers and organizers. These stakeholders come from several origins and core businesses. Historically, the infrastructure was carried by broadcasting, mostly cable TV channels. This legacy channel changed with interconnectivity and players such as Twitch, Trovo, and YouTube. Alongside these major platforms, event operators are providing their own viewing platforms (e.g. ESL FACEIT Group). Similarly, content creators and users like influencers or pro-players broadcast their own channel.

The distribution of esports is not as financially lucrative as other sports, as most events are broadcast via online platforms.

Streaming platforms are also technology companies. They invest heavily in their infrastructures to ensure that their customers, wherever they may be, have access to their content and the same quality of service. Streaming companies rely on a fixed revenue from monthly subscriptions. They may also collect advertising money either through commissions on product sales, or via partnership and revenue sharing programs on their sites. Sponsorship is another source of revenue. As these companies are subsidiaries of major tech firms, they have an increased bargaining power to deal with publishers and events holders: they may strike exclusive deals with publishers of popular esports titles. Hereafter, distributing esports is not as financially rewarding as other sports because most esports events are streamed via online platforms.

Event operators, organisers and leagues

New players have emerged, inspired by the model of sports and events management. They contributed to the professionalisation of esport through the creation of dedicated teams and the organisation of competitions.

Teams competing for championships consist of associations or companies that employ players to participate in competitions as an identified team. They are part of federations, associations and leagues divided into divisions and smaller competitions involving more players, all year round. They design larger forms of competition and provide them a legal and regulatory framework. Federations, leagues and associations are constituted as the governing bodies. They build and operate infrastructures for esports, establish, maintain and run academy, provide computer training, and set up the global framework of competitions.

Third-party tournament organizers must often pay significant fees to publishers. Despite powerful players from the digital or sport sector, some independent event organisers may nevertheless thrive. Electronic Sports League (ESL, founded in 2000 in Germany) is one of the oldest esports companies which organise competitions worldwide, hosts high-profile tournaments for professional players.

Teams and players

Historically, players started competing in a rather informal way. Professional players were self-organising. Since that beginning, professional esports organisations have been set up to manage and supervise esports “athletes” and teams.

Scholz, and Nothelfer9 break down the progress of professionalisation into four steps. Initially, players competed informally against each other as a hobby. Then, the organisation of amateur esports gets formalised within a club and competition with other players takes place. Next, semi-pro esports emerged where professional structures were set up and looked for external support (coaches, sponsors, etc.). These entities provided a talent pool for professional players. Finally, the structuring of professional esports takes place: players under contract participate to the highest level of competitions and join communities of players such as the US Overwatch Players Association. Professional teams are forming around game titles and maintaining rolls of players to compete in tournaments globally.

Esports teams derive most of their revenue from sponsorships and merchandise sales.

An important dimension of professionalisation is the way to build sustainable earnings10,11. Esport global revenue share includes distributing subscription, donation, and advertisement revenues, as well as a part of sponsorship and media right revenue. Lastly, revenue share incorporates in-game digital goods. Esports teams derive most of their revenue from sponsorships and merchandise sales (see Fig. 2), unlike traditional sports teams earning most of their income from ticket sales and broadcast right. Regarding players, the basic source of income is the salary received from their team: an average salary is $50,000–$60,000 annually12. But players can also add other streams of revenue13. Like in traditional sports, the range of remuneration is pretty broad and varies based on the size of the team, the ability of the player, the type of game, the kind of competitions.

An economic situation in transition

Esport illustrates the take-off of a niche market on the fringes of a major sector. Fuelled by interconnectivity and ultra-high broadband networks, cheaper devices and the creativity of the game developers, what started as an informal meeting of players competing together in an Internet café or an arcade venue, morphed into a full-blown international industry. This results in the growth and gradual professionalisation of the activity, but also in the difficulty of transitioning to an autonomous and sustainable ecosystem.

Nevertheless, most of the stakeholders are far from being profitable. A nascent industry takes some time to stabilise and to work out the relevant business models, especially as free content remain present. Such a feature implies rethinking the traditional models of the original sports and video game sectors in order to find innovative source of revenues. Secondly, the professionalisation of an activity involves reconciling sometimes conflicting objectives between value chain players. It does not necessarily strengthen the ability to coordinate and to define a common framework.