A digital twin is the digitisation of a given environment: this very general definition encompasses many very varied applications. Interactive digital twins allow a human to interact with the virtual environment, thanks to tracking sensors, control organs (joystick, joysticks, etc.) or force feedback interfaces (haptic interfaces). These tools are interdisciplinary in several respects: in terms of their fields of application (medicine, maritime industry, etc.) and the sciences they mobilise (mechanical, thermal, biological, etc.).

Anders Thorin, a research engineer at the CEA List’s Interactive Simulation Laboratory, has been working in the team developing the XDE Physics software for the past twenty years. This software, which allows the creation of digital twins in the field of robotics, has attracted the interest of Technip Energies for projects in the maritime sector. The researchers then developed new functionalities to meet the needs of the company. Today, it has been repackaged in a software package called “CETO”, dedicated to interactive maritime simulation. It allows immersion in virtual reality (VR) within a crane on board a floating structure, which can be used for forecasting and risk assessment for complex lifting operations, or for staff training.

Replicating the sea and its environment

CETO makes it possible to reproduce the physical characteristics of the sea, its environment, and numerous objects from the maritime world – container ships, port cranes, cables, pipes – in an interactive simulation.

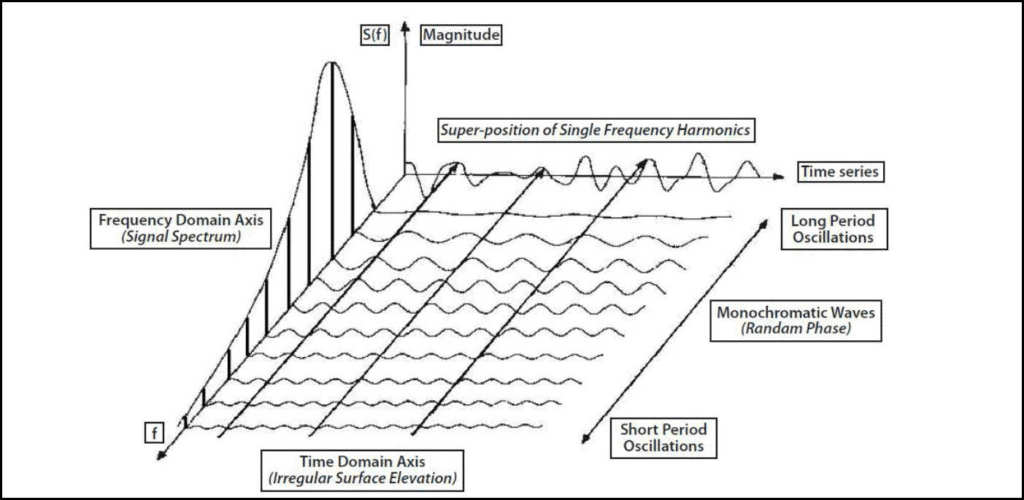

The first step was the physicalisation of the environment to be studied – a step in which the researchers will model the constituent elements of the scenario, starting with the sea. “To model the sea, we typically use 600 spectral components,” says the researcher. Each spectral component corresponds to a sinusoidal wave, which has several parameters: amplitude (from the peak to the trough of the wave), direction, phase, and frequency. Other environmental conditions must be considered during the interactive simulation: wind and current, for example.”

After an initial simulation prototype, the researchers were able to improve the precision and therefore the realism of the simulation by increasing the level of detail of the models: taking into account propellers, cables, cranes, etc., with a view to knowing, or rather verifying, how it will react to the movement of the sea, the wind, the swell and so on. “Physicalisation is not always necessary depending on the purpose,” he says, “but when it is, the interactive nature means that the physical equations have to be solved in real time, which often involves a simplification phase of the physical models.”

For example, a slender rigid structure is modelled by a ‘beam’ of a certain size, which is a simplification to allow real-time simulation in XDE Physics. With this step, the question may arise: can a digital twin be so accurate that it reproduces reality, despite being a simplification? The researcher no longer asks this question: “in science, everything is a model. Even a concept as simple as a right angle does not exist in nature. The challenge for a digital twin in interactive simulation is to adopt a model that is sufficiently precise to be of practical use in a given context. In addition, the model equations chosen must be able to be solved quickly enough with the hardware provided. Perfect accuracy is not required to obtain useful results, and so much the better, as this is not attainable.”

A good example of this is putting a deformable pipe in the water. Once the pipe has been modelled as a beam, the laboratory team will be able to assess its strength during lifting and lowering operations, depending on the weather conditions and the actions of the crane operator in the virtual world. This multitude of digitally combined elements allows for an interactive simulation of any desired scenario. This allows the user to assess whether the pipe will withstand handling without having to achieve perfect accuracy in the simulation. All this is much safer and more economical than real-life testing.

From forecasting to training

A digital twin can therefore allow scenarios to be validated before being applied in the physical world. The uses are therefore countless, and the advantages considerable. “There is a real benefit to this type of simulation,” says Anders Thorin. “Firstly, in terms of cost, because it requires less time to carry out a project, limits the need to move equipment, avoids the use of models, etc. And in terms of reproducibility, because each scenario can be validated on the same simulation, the parameters being able to be modified as required.”

The uses of the digital twin are countless, and the benefits considerable.

In fact, if we want to estimate the difference in movement that a ship can have in calm water, compared to rough water, only the parameters that influence the dynamics of the water and the wind need to be changed, namely: the direction of the wind, its speed, and its constancy, etc. “It is a form of forecasting an event under certain predefined conditions – wind, swell, current, and many others,” adds the researcher.

However, the usefulness of this type of digital twin does not stop at scenario ‘forecasting’. Having a real virtual world, accessible through a VR headset, all as true as possible to the physical realities of the elements around us, would allow for effective use in training. “Technip Energies adjusted a chair to replicate (this time in the real world) the cabin of a crane with its joysticks,” he explains. “This allowed a crane operator to come on site for training, in addition to hands-on practice.”

Coupled with its two main benefits (cost and reproducibility), such software would have an undeniable added value to crane operator training, especially for dealing with extreme situations, such as high winds.