Generative AI: energy consumption soars

- The energy consumption of artificial intelligence is skyrocketing with the craze for generative AI, although there is a lack of data provided by companies.

- Interactions with AIs like ChatGPT could consume 10 times more electricity than a standard Google search, according to the International Energy Agency (IAE).

- The increase in electricity consumption by data centres, cryptocurrencies and AI between 2022 and 2026 could be equivalent to the electricity consumption of Sweden or Germany.

- AI’s carbon footprint is far from negligible, with scientists estimating that training the BLOOM AI model emits 10 times more greenhouse gases than a French person in a year.

- It seems complex to reduce the energy consumption of AI, making it essential to promote moderation in the future.

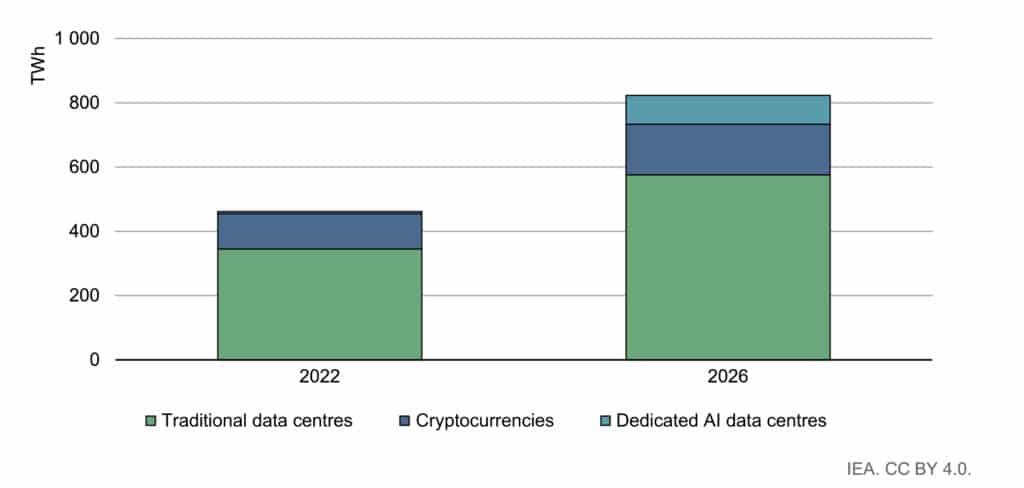

Artificial intelligence (AI) has found its way into a wide range of sectors: medical, digital, buildings, mobility, etc. Defined as “a computer’s ability to automate a task that would normally require human judgement1”, artificial intelligence has a cost: its large-scale deployment is generating growing energy requirements. The IT tasks needed to implement AI require the use of user terminals (computers, telephones, etc.) and above all data centres. There are currently more than 8,000 of these around the world, 33% of which are in the United States, 16% in Europe and almost 10% in China, according to the International Energy Agency2 (IEA). Data centres, cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence will account for almost 2% of global electricity consumption in 2022, representing electricity consumption of 460 TWh. By comparison, French electricity consumption stood at 445 TWh in 20233.

AI electricity consumption: a lack of data?

How much of this electricity consumption is actually dedicated to AI? “We don’t know exactly” replies Alex de Vries. “In an ideal case, we would use the data provided by the companies that use AI, in particular the GAFAMs, which are responsible for a large proportion of the demand.” In 2022, Google provided information on the subject for the first time4: “The percentage [of energy used] for machine learning has held steady over the past three years, representing less than 15% of Google’s total energy consumption.” However, in its latest environmental report5, the company provides no precise data on artificial intelligence. Only the total electricity consumption of its data centres is given: 24 TWh in 2023 (compared with 18.3 TWh in 2021).

In the absence of data provided by companies, the scientific community has been trying to estimate the electricity consumption of AI for several years. In 2019, an initial article6 threw a spanner in the works: “The development and training of new AI models are costly, both financially […] and environmentally, due to the carbon footprint associated with powering the equipment.” The team estimates that the carbon footprint of the total training for a given task of BERT, a language model developed by Google, is roughly equivalent to that of a transatlantic flight. A few years later, Google scientists believe that these estimates overestimate the real carbon footprint by 100 to 1,000 times. For his part, Alex de Vries has chosen to rely on sales of AI hardware7. NVIDIA dominates the AI server market, accounting for 95% of sales. Based on server sales and consumption, Alex de Vries projected electricity consumption of 5.7 to 8.9 TWh in 2023, a low figure compared with global data centre consumption (460 TWh).

The generative AI revolution

But these figures could skyrocket. Alex de Vries estimates that by 2027, if production capacity matches the companies’ promises, NVIDIA servers dedicated to AI could consume 85 to 134 TWh of electricity every year. The cause: the surge in the use of generative AI. ChatGPT, Bing Chat, Dall‑E, etc. These types of artificial intelligence, which generate text, images or even conversations, have spread across the sector at record speed. However, this type of AI requires a lot of computing resources and therefore consumes a lot of electricity. According to the AIE, interactions with AIs such as ChatGPT could consume 10 times more electricity than a standard Google search. If all Google searches – 9 billion every day – were based on ChatGPT, an additional 10 TWh of electricity would be consumed every year. Alex De Vries estimates the increase at 29.3 TWh per year, as much as Ireland’s electricity consumption. “The steady rise in energy consumption, and therefore in the carbon footprint of artificial intelligence, is a well-known phenomenon,” comments Anne-Laure Ligozat. “AI models are becoming increasingly complex: the more parameters they include, the longer the equipment runs. And as machines become more and more powerful, this leads to increasingly complex models…”. For its part, the International Energy Agency estimates that in 2026, the increase in electricity consumption by data centres, cryptocurrencies and AI could amount to between 160 and 590 TWh compared with 2022. This is equivalent to the electricity consumption of Sweden (low estimate) or Germany (high estimate).

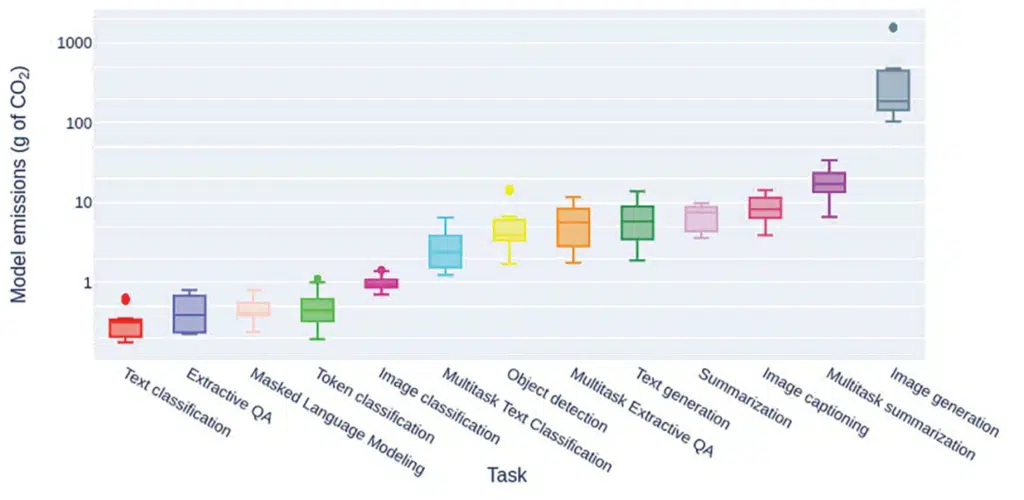

The processing needs of AI can be explained by different phases. AI development involves an initial learning phase based on databases, known as the training phase. Once the model is ready, it can be used on new data: this is the inference phase10. The training phase has long been the focus of scientific attention, as it is the most energy-intensive. But new AI models have changed all that, as Alex de Vries explains: “With the massive adoption of AI models like ChatGPT, everything has been reversed and the inference phase has become predominant.” Recent data provided by Meta and Google indicate that it accounts for 60–70% of energy consumption, compared with 20–40% for training11.

Carbon neutrality: mission impossible for AI?

While AI’s energy consumption is fraught with uncertainty, estimating its carbon footprint is a challenge for the scientific community. “We are able to assess the footprint linked to the dynamic consumption of training, and that linked to the manufacture of computer equipment, but it remains complicated to assess the total footprint linked to use. We don’t know the precise number of uses, or the proportion of use dedicated to AI on the terminals used by users,” stresses Anne-Laure Ligozat. “However, colleagues have just shown that the carbon footprint of user terminals is not negligible: it accounts for between 25% and 45% of the total carbon footprint of certain AI models.” Anne-Laure Ligozat and her team estimate that training the BLOOM AI model – an open-access model – emits around 50 tonnes of greenhouse gases, or 10 times more than the annual emissions of a French person. This makes it difficult for the tech giants to achieve their carbon neutrality targets, despite the many offsetting measures they have taken. Google admits in its latest environmental report: “Our [2023] emissions […] have increased by 37% compared to 2022, despite considerable efforts and progress in renewable energy. This is due to the electricity consumption of our data centres, which exceeds our capacity to develop renewable energy projects.”

Limiting global warming means drastically reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. Is AI at an impasse? “None of the arguments put forward by Google to reduce AI emissions hold water” deplores Anne-Laure Ligozat. “Improving equipment requires new equipment to be manufactured, which in turn emits greenhouse gases. Optimising infrastructures – such as water cooling for data centres – shifts the problem to water resources. And the relocation of data centres to countries with a low-carbon electricity mix means that we need to be able to manage the additional electricity demand…” As for the optimisation of models, while it does reduce their consumption, it also leads to increased use – the famous ‘rebound’ effect. “This tends to cancel out any potential energy savings,” concludes Alex de Vries. “My main argument is that AI should be used sparingly.”