High-speed trains: is rail always better for the environment?

- The Grand Projet ferroviaire du Sud-Ouest, which aims to link Bordeaux and Toulouse via high-speed lines (LGV), is sparking debate.

- While trains are an environmentally friendly means of transport, the environmental and economic consequences of building the project's infrastructure are raising questions.

- The project's negative externalities include deforestation (around 4,800 hectares of land) with significant impacts on the environment.

- Nevertheless, the project would save valuable time in economic terms and encourage a modal shift equivalent to more than 2.3 million tonnes of oil equivalent over 50 years.

- Ultimately, the project is a complex challenge because the arguments on both sides are valid but involve making major political decisions.

The Grand Projet ferroviaire du Sud-Ouest (GPSO) continues to move forward despite opposition. Work has begun to the south of Bordeaux with a view to linking the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region with Toulouse via a high-speed line (LGV). Ultimately, the project will make it possible to travel from one city to the other in just 1 hour 05 minutes (1 hour 20 minutes with stops), but also to link Toulouse to Paris (via Bordeaux) in around 3 hours 25 minutes1 – reducing travel times by between 49 minutes and 56 minutes. Some environmentalists are opposed to this project, even though the train is one of the means of transport which is favourable for the environmental transition.

The train is in fact one of the modes of transport to be favoured for the ecological transition. A fact that can easily be verified using ADEME’s My transport impact tool. The TGV emits 2.93 gCO₂eq per kilometre, whereas a combustion engine car emits 218 gCO₂eq, almost 75 times more. A journey from Toulouse to Bordeaux by TGV, according to this tool, corresponds to an emission of 0.77 kgCO₂eq, compared with 53.4 kgCO₂eq by car2.

So why might environmentalists oppose the development of the train? The reason is that the way in which emissions are calculated omits those resulting from the construction of infrastructure.To reach speeds of up to 320 km/h, for example, certain constraints must be met. The lines must avoid excessively sharp bends or steep gradients, limiting the possibility of bypassing natural areas, and also means the need for new infrastructure. Hence, it’s not the train as such that’s being challenged, but rather the scale of the works and the ecological and economic consequences that their construction will cause. The GPSO therefore raises an essential question: how is a project of this scale justified in terms of its cost and environmental impact?

Socio-economic value and environmental impact

The GPSO represents an investment of €14.3 billion3 (estimated costs in 2021), of which €10.3 billion will be devoted to the Bordeaux-Toulouse line. A total of 418 km of lines4 are to be built between now and 2035 – 252 km to link Bordeaux and Toulouse, with the remainder extending the lines to Dax and, eventually, to Spain. A report on the socio-economic assessment of public investment5 is used to evaluate such a project in terms of benefits/costs. Patricia Perennes, an economist specialising in transport and a consultant with Trans-Missions, has worked for Réseau Ferré de France (RFF) and questions this type of assessment.

“The Quinet report does an enormous job of synthesising everything that is being done in international research. It proposes methods for valuing the externalities of public investment”, she explains. “For transport infrastructure, each externality, whether positive or negative, is converted into a monetary value.” In this way, a sort of balance is formed between the value of the positive and that of the negative, making it possible to validate an investment project.

“There are externalities that are simpler to value, such as the quantity of CO₂ that a project will emit, the cost of its construction, or the time it will save,” continues the economist. “There are also externalities that can be complicated to value, such as deforestation, or the disruption of an ecosystem. In these cases, compensation measures will be more appropriate. But planting a pine forest and cutting down trees that could be a hundred years old is not really the same thing.” In this case, around 4,800 ha of land6 are affected – 770 ha for Bordeaux-Sud Gironde, 2,330 ha for Sud Gironde-Toulouse and 1,700 ha for Sud Gironde-Dax. The impact on biodiversity, despite compensatory measures, is therefore undeniable.

An expert report7, produced by the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, assesses the various impacts of this project and the benefits it will bring, by comparing it with another so-called ‘optimised’ scenario, itself produced by RFF. The difference is that the optimised scenario focuses on renovation, and therefore on the use of existing lines. This scenario will not bring the same time savings for users – 19 minutes will be saved compared with the current flow – but it will have a much lower environmental impact and cost. The conclusion of this report is quite telling: “The experts were able to note that, faced with impacts of different kinds, the assessment can only be a political one, as it depends on the adoption of a system of values; it is therefore beyond the competence and remit of the experts. The issue is whether to build a new line between Bordeaux and Toulouse or to upgrade the existing line. This is an eminently political issue.”

The promise of modal shift

On the other side of the balance, there are the positive externalities of the project: “For TGV projects, saving time is a key issue,” explains Patricia Perennes. “It is also quite expensive, especially for professionals. In 2010, for example, each hour saved by professionals in the Île-de-France region was valued at €22. And these are the figures for 2010, so with inflation it’s bound to have gone up.” Another important part of positive externalities is modal shift. It is estimated that, through the ‘transfer of traffic from road and air to rail’, the GPSO would enable ‘a total saving of more than 2.3 million tonnes of oil equivalent over 50 years8. A substantial shift also represents a major benefit in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, given that in 2020 road transport accounted for 94.7% of emissions from the transport sector, itself the leading source of greenhouse gases in France9 (28.7%)[…].

This interest in modal shift is also reflected in the freeing up of existing tracks to give priority to rail freight in particular. This argument is also being put forward for another French high-speed rail project that is the subject of much debate. The Lyon-Turin line has also been in the news for years. In his 1998 report, engineer Christian Brossier wrote that there were 100 goods trains and between 24 and 28 passenger trains a day on the existing lines in the Alps. However, after numerous investments in the region, the number of trains has fallen year on year, while the number of HGVs using one of the two tunnels to cross the Alps has remained fairly stable10.

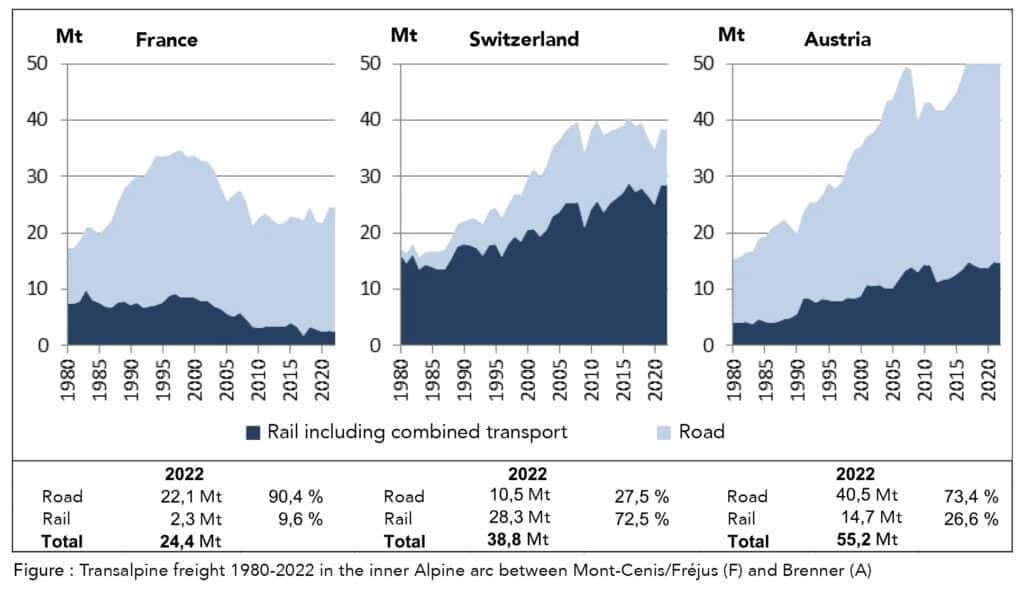

Using data from 1998, a simple calculation shows the potential of rail for transalpine transport in France: assuming 100 trains a day, each loaded with 30 containers carrying around 18 tonnes, and running 300 days a year, 16 million tonnes of goods could be transported annually. And, as Switzerland is doing, 2/3 of heavy goods vehicles would be taken off the road in the Northern Alps (Fréjus and Mont-Blanc). In comparison, in 2022, rail’s share of transalpine freight transport in France will be just 9.6%, or 2.3 million tonnes, while 22 million tonnes will be carried by road. These figures highlight the gap between rail’s potential capacity and its actual use. This is why opponents of the projects will tend to favour alternatives that involve working on the operation and renovation of existing lines to make the best use of their capacity. In fact, this is a national question that has been raised: how is it that Switzerland, with a network of 3,265 km of track, manages to run around 15,000 trains a day, while France, with its 27,483 km, only runs a similar number?

Finally, as Patricia Perennes points out: “There is no doubt that if we talk about the flow on these new lines, the ecological impact will be beneficial, but if we take into account the construction phase, the calculation is different.” And despite the weight of the construction phase, the GPSO is still expected to be carbon neutral by 2056. The dilemma of our time is embodied in this project: reconciling innovation, efficiency and environmental protection is no easy task.