Hydrogen in transport: everything you need to know in 10 questions

- Hydrogen is an energy vector generally produced from fossil fuels, which emit a lot of CO2 – reducing its carbon footprint is a major challenge.

- It will account for only 0.003% of transport energy consumption worldwide in 2021.

- Hydrogen is particularly valuable when used in conjunction with electricity, which is currently the preferred source of carbon reduction.

- If hydrogen-powered bicycles or cars are energy inefficient, hydrogen could prove useful, especially for heavier vehicles (buses, trucks, etc.).

- The potential of hydrogen must be studied with caution in view of the challenges that remain.

#1 What is hydrogen? Is it an energy source?

Hydrogen is both the smallest and most abundant atom in the universe. It is notably present in water (H2O) and often associated with carbon in organic molecules, and thus constitutes 92% of the atoms in the universe and 63% of the atoms in our bodies (and respectively 75% and 10% by mass)1.

But when we talk about hydrogen in the energy transition, we are generally talking about the dihydrogen (H2) molecule. With the exception of a few little-known and little-exploited native hydrogen deposits, hydrogen is not a source of energy that can be found directly in nature. It must therefore be produced from other energy sources and, as such, is referred to as an energy carrier (like electricity). Hence, the question is whether or not this method of production generates significant CO2 emissions.

#2 How is hydrogen produced? Is it low-carbon?

There are several methods of producing hydrogen. To date, hydrogen is mainly produced from fossil fuels, making the production process generates a large amount of CO2. This is the case for 99.3% of the world’s hydrogen production, mainly via the steam reformation of methane from fossil gas (62% of production), followed by coal gasification or co-products of oil refining (19% and 18% respectively). Low-carbon production is possible via two main techniques, which represent only a very small fraction of current production. Fossil fuel-based production, which is associated with carbon capture and storage, accounts for 0.7%, and water electrolysis, which is expected to increase significantly in the light of recent announcements, will account for only 0.04% by 20212.

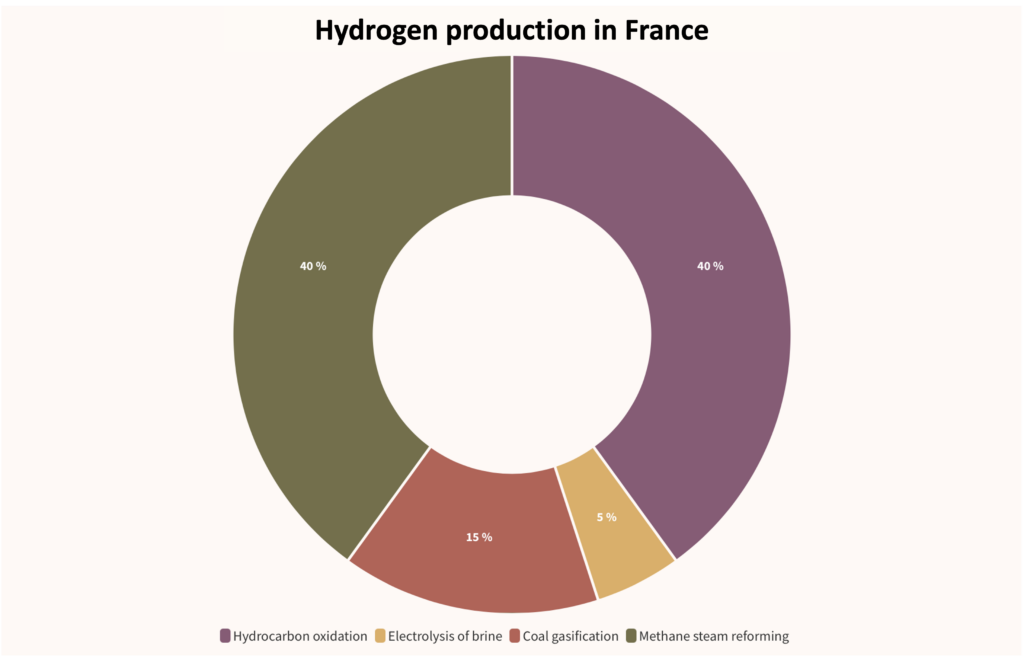

In France, 95% of hydrogen is produced using fossil fuels. The remaining 5% comes from the electrolysis of brine, mainly for the production of chlorine4. The 2018 French hydrogen plan’s choice to decarbonise production focuses on water electrolysis, with the aim of accounting for just over half of hydrogen production in 20305.

#3 What are the uses of hydrogen?

Hydrogen can be used for two purposes: either as a reagent to produce something else, or as an energy carrier. Today, hydrogen is mainly used in industry as a reagent, both globally and in France. In France, hydrogen is used in particular for fuel refining (60%), to produce ammonia mainly for agricultural fertilisers (25%), and in chemistry (10%)6.

Several challenges and uses of hydrogen are envisaged in the future for the energy transition, to be considered in terms of order of merit7. First and foremost, it is a question of reducing carbon emissions from the current uses of hydrogen in industry. It may also be a question of replacing other uses by low-carbon hydrogen, whether for the reduction of carbon emissions in industry or transport, or to participate in the reduction of carbon emissions from current gas networks. Finally, hydrogen could contribute to the storage of electricity, by offering a flexible solution to ensure the balance of the electricity network.

#4 Hydrogen and transport: where do we stand? What is the rollout timeframe?

Hydrogen in transport is still in its infancy. Despite the 60% increase in consumption compared to 2020, hydrogen will represent only 0.003% of transport energy consumption worldwide in 2021.

Hydrogen is currently most widely used in road vehicles, although at a very low level. At the end of 2021 in France, there were only a few hundred hydrogen-powered cars (and about 1,000 fewer of them have been sold than electric cars since the beginning of 20228), 2 heavy goods vehicles, 4 specialised self-propelled vehicles (SSVs: e.g. refuse collection vehicles), and 22 buses (i.e. less than 0.1% of the fleet9).

For reasons of energy efficiency and carbon footprint, electric is to be favoured where possible.

However, heavy mobility is the second focus of the 2018 French hydrogen plan and the 2020 national strategy for the development of low-carbon hydrogen10. The objective set in 2018 is to reach 20,000 to 50,000 light commercial vehicles, the equivalent of 0.7% of the current vehicle fleet, and 800 to 2,000 heavy vehicles by the year 2028. The upper limits correspond to the equivalent of 0.9% of the current commercial vehicle fleet and 0.3% of the heavy vehicle fleet11.

For rail transport, hydrogen-powered trains are already running in Germany and the first commercial runs are planned for 2025 in France12. For ships, experiments are underway for low-capacity ships over limited distances. However, other decarbonisation solutions are generally preferred to hydrogen, particularly for maritime transport (biogas, methanol, ammonia, etc.). Finally, Airbus is targeting 2035 for the marketing of a hydrogen-powered aircraft capable of short and medium-haul flights.

#5 Decarbonisation of transport: which technology(ies) should be prioritised?

The withdrawal of oil from transport is essential to achieve the objective of carbon neutrality in France by 205013. There are four possible energy sources for transport: electricity, hydrogen, gaseous fuels (fossil or renewable gas) and liquid fuels (oil or biofuels). Synthetic fuels can also be produced by combining hydrogen with CO2, a technology that is not yet fully developed.

Among these different technologies, electricity is the least carbon-intensive, at more than 90% in France, while the other technologies (hydrogen, gaseous and liquid fuels) are more than 90% dependent on fossil fuels. Furthermore, the potential for the production of renewable gas and biofuels is severely limited by the available biomass resources, which requires first and foremost a sharp reduction in the consumption of gas and liquid fuels in the economy in order to reduce their carbon emissions.

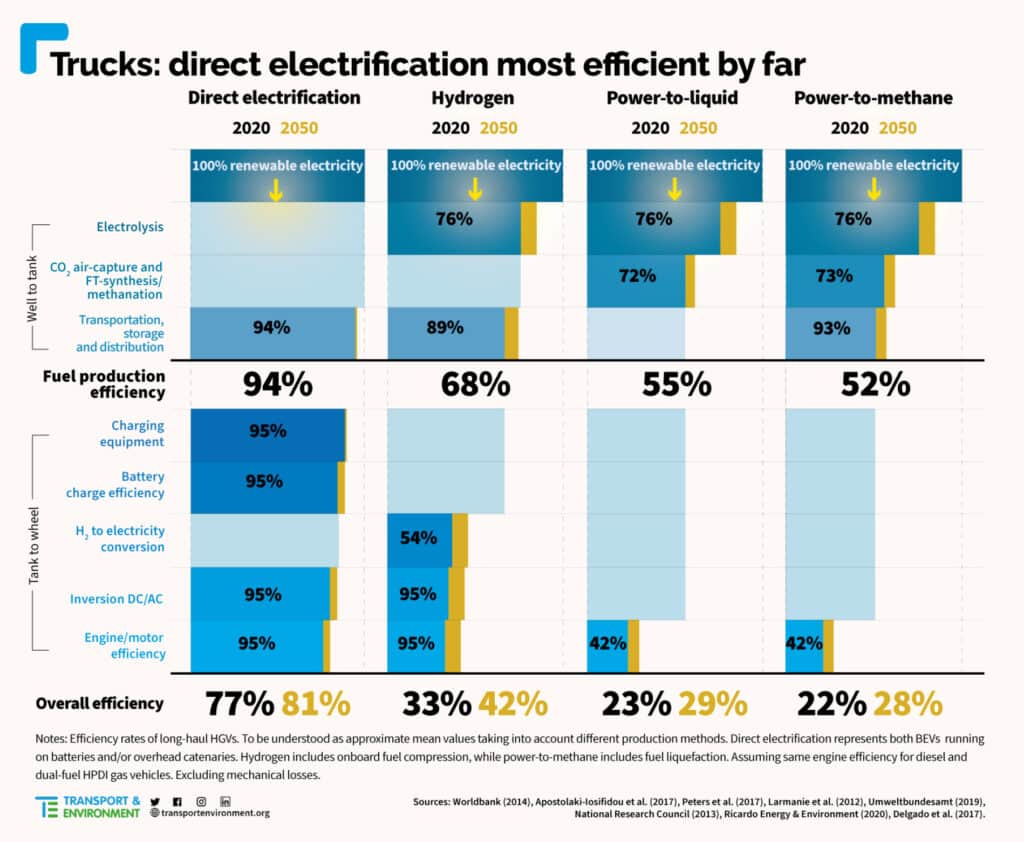

With regard to the electric and hydrogen technologies, hydrogen is less energy efficient than the direct use of electricity in an electric vehicle with batteries. Hydrogen can be used in a vehicle in two ways: either as a fuel in a hydrogen engine, which is much less efficient than electric engines; or by converting the hydrogen back into electricity via a fuel cell located in the vehicle, and then using this electricity in an electric engine. In this second case, and given the energy losses of these transformations, it takes about 2.3 times more electricity to run a hydrogen vehicle than an electric vehicle15.

This lower efficiency multiplies electricity costs, as well as vehicle emissions if the electricity used is not very low carbon. It also requires larger volumes of electricity to reduce the carbon emissions of transport. Decarbonising all land transport (cars, trucks, buses, trains, etc.) in Europe via electric vehicles would require the equivalent of 43% of the electricity produced in 2015, and 108% in the case of hydrogen vehicles. These figures increase further when considering shipping and aviation16.

To improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon footprints, electricity is therefore to be prioritised whenever possible, as is the case for light road vehicles (two-wheelers, cars, or even commercial vehicles). Hydrogen will find its relevance as a complement to electric power, particularly when there is a need for high charge rates, long ranges and/or very short recharging times. It is moreover through these advantages that hydrogen gives hope or may give the illusion that it will be possible to maintain the transport behaviours and uses currently permitted by oil in the future.

#6 What is the carbon footprint and other environmental impacts of transport?

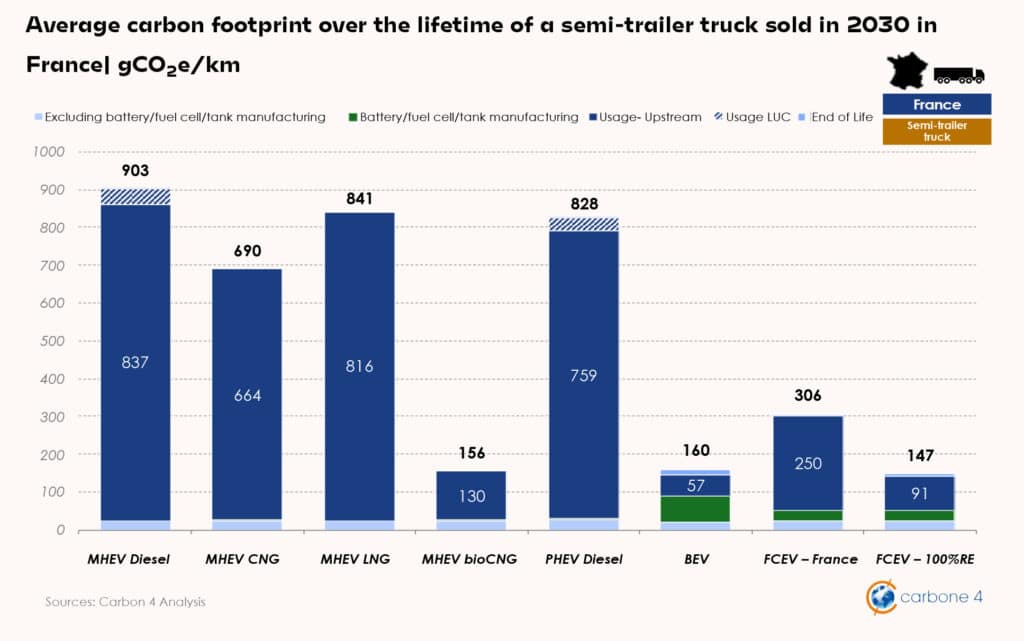

When hydrogen is produced by electrolysis with renewable or nuclear electricity, the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of a bus sold in 2020 (or a truck sold in 2030) are reduced by 6 times compared to diesel. This places hydrogen technology at similar emission levels to electric buses or trucks recharged in France, as well as to vehicles using biogas. On the other hand, if hydrogen is produced by electrolysis with the average French electricity mix, the hydrogen tractor unit goes from 6 times less to 3 times less emissions than the diesel tractor unit; it becomes slightly more emissive with the average European mix and even 60% more emissive with the German electricity mix17.

Thus, the decarbonisation of hydrogen production is an essential condition to ensure significant climate benefits from the development of hydrogen in transport. The impact of emissions from the electricity mix is even stronger for emissions from hydrogen vehicles than for emissions from electric vehicles, due to the lower efficiency of the hydrogen chain and thus the higher quantities of electricity per kilometre travelled.

From an environmental point of view, and compared to battery-powered electric vehicles, the main advantage of hydrogen is the lower battery capacity required. This reduces the pressure on resources and the pollution caused by the exploitation of lithium, cobalt, or nickel. The hydrogen sector also involves the consumption of metals, in particular platinum for fuel cells and electrolysers, the criticality of which will depend on the level of development of the sector19. Finally, the greater need for electricity for hydrogen vehicles (when produced by electrolysis) requires more metals to produce electricity.

#7 What are the costs of hydrogen?

Hydrogen technologies are currently more expensive than oil or electricity, both in terms of the cost of vehicles and of energy. However, the additional purchase costs vary greatly depending on the mode of transport and the development of the vehicle market. And the additional energy costs depend heavily on the method of hydrogen production, with production via electrolysis being about twice as expensive today as steam reforming of fossil gas. Transport and distribution costs are also significant, especially if there are significant distances between the production and consumption sites.

In total, the Department of Transportation estimated in 2018 that the total cost of ownership is around 20–50% higher for a hydrogen vehicle than for the combustion equivalent. With hydrogen from electrolysis, the total cost of ownership for trucks, buses and coaches is 1.5 to 3 times higher for hydrogen than for diesel20. However, costs are projected to fall by around half by 2030 for production via electrolysis, which will also affect current balances21.

However, cost projections between technologies and energies are subject to considerable uncertainty. Hydrogen’s competitiveness could therefore vary greatly depending on the evolution of technical, geopolitical, resource or deployment constraints of the different energies. Finally, it will depend on the possible support or taxation levels of the energies or technologies by the public authorities.

#8 What are the technical and organisational challenges for the future?

The technical challenges faced by the hydrogen sector remain considerable if it is to be developed for use in the transport sector. As this gas is particularly small, light, and flammable, the risks of leaks or accidents must be controlled to ensure the safety of vehicles, storage or transport of hydrogen. Storage in vehicles also requires the compression of hydrogen, an energy-intensive process, and the use of tanks that make vehicles very heavy.

Hydrogen technologies are currently more expensive than oil or electricity, both in terms of vehicle and energy costs.

Also, the low volumetric energy density (quantity of energy contained in a given volume) of hydrogen requires that the production of hydrogen should take place as close as possible to the place of consumption, in order to limit the energy and financial costs of its transportation. This calls for consideration to be given to the organisation of ecosystems enabling production and use to be shared between several modes or economic sectors in the same place. To ensure the overall coherence of these regional plans, it will also be necessary to ensure a progressive network of hydrogen production and distribution infrastructures for the heavy road modes.

Finally, the technical challenges vary according to the mode of transport or the vehicle, which also determines the timeframe for the diffusion of hydrogen. For example, for air transport, the low volume density potentially requires a review of the shape of the aircraft or at least the shape, weight and size of the tanks, which is one of the major technical challenges in the development of a hydrogen powered aircraft.

#9 What is the future for different modes of transport?

For road transport, hydrogen will not be relevant for the lightest vehicles, which are better suited to battery-powered electric vehicles. Hydrogen-powered bicycles or cars, which are energy inefficient and much more expensive financially, should therefore be forgotten as mass-market solutions, apart from a few niche uses. On the other hand, hydrogen could be more useful for the heaviest modes (heavy goods vehicles, buses, and coaches, etc.) and when the distances are too long for battery powered electric vehicles.

As far as rail is concerned, hydrogen trains could be a good alternative to diesel and when traffic is too low to justify the electrification of the line22. For ships, hydrogen will be too difficult to use to reduce the carbon footprint of long-distance maritime transport, which could, however, turn to hydrogen derivatives such as ammonia, methanol or electrofuels. On the other hand, hydrogen could be adapted for river transport, which corresponds to smaller volumes and distances.

Finally, when it comes to air transport, the technological gamble has already been set in motion and is justified by the limits of the other alternatives to oil, in particular the competition for the use of biomass for biofuels, as well as the fact that the development of synthetic fuels and hydrogen derivatives is still in its early stages. On the other hand, this gamble is still subject to considerable uncertainty. Therefore, by 2050, hydrogen will only be able to represent a small part of the sector’s consumption, up to a maximum of 7% of flights departing from and arriving in France, according to ADEME’s three scenarios for the ecological transition of the aviation sector.

Electrofuels, derivatives of hydrogen, represent a greater potential for the reduction of carbon emissions, up to 38% of the energy mix in 2050. However, they only become significant in the 2030s, with major scaling up challenges and the requirement to be produced with very low carbon electricity to be advantageous from a climate point of view23.

#10 So what should we learn from this?

Hydrogen should not be seen as a miracle solution for reducing the carbon footprint of transport, because it is not. It is less energy efficient, largely carbon-based and more expensive than electric power today, and the production of low-carbon hydrogen may not be on a grand scale for several more years, which limits its capacity to contribute to the necessary reduction in emissions from the sector in the short term24.

In France, the hydrogen plan foresees a reduction in emissions of around 6 MtCO2 by 203025, i.e. a reduction equivalent to 1.4% of current national emissions (418 MtCO2e in 202126). While the potential is far from negligible, it remains limited, given that the European objective is now to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 199027.

Hydrogen should not be seen as a miracle solution for reducing the carbon footprint of transport, because it is not.

However, the potential of low-carbon hydrogen should not be totally discounted, especially for industry or as a complementary solution for transport in the longer term – which requires investment and a boost to the sector today28. A certain amount of public support for the development of the sector is therefore necessary, but with three caveats:

- The possibilities must be carefully examined and developed without haste, in view of the many challenges (technical, economic, low-carbon production, etc.) that remain for the sector. Without this necessary vigilance, there would be a great risk of rushing to develop uses that would remain carbon-based in the future

- The development of hydrogen in transport must above all be developed pragmatically, rather than on the basis of false beliefs and technological illusions, which is still too often the case.

- Above all, as with other decarbonation technologies, hydrogen must not be used as a pretext to hide the urgency of energy sobriety in transport in order to rapidly reduce its emissions… an argument abundantly used for example by the airline sector with the hydrogen plane, in order to distract from the necessary moderation of its traffic.

Without these precautions, hydrogen could do more harm than good to the energy transition in transport…