Living without ageing: myth or reality?

- Numerous investments and research projects are aimed at reinvigorating biomedical research to better understand the mysteries of longevity.

- Controlling the ageing process means avoiding all the diseases that arise from the wear and tear of our organs, such as neurodegenerative diseases.

- It could be possible to reverse the ageing process by reprogramming the cells to make them younger or by changing the blood composition.

- INSEE estimates that in France, at least 11% of children born after 2000 can hope to become centenarians or even 'supercentenarians'.

- But if we live forever, we should ask ourselves whether we will die of boredom or depression.

In recent years, large sums of money have been poured into reinvigorating biomedical research to better understand ageing. This new interest complements previous efforts to understand the mysteries of longevity. Since life expectancy is increasing overall, the challenge is to ensure that these added years are healthy. To achieve this goal, scientists are being asked to push back the wall of natural longevity1 so that we can live comfortably beyond 115 years old2. According to ageing specialists, this is no longer a utopic quest as it was back in the days of Gilgamesh or Faust. On the other hand, if it were to become a reality, this hope would subject our lives, and above all the balance of our societies which are so sensitive to demographic change, to immeasurable upheaval. Let’s take a look at the scientific and societal aspects of this quest for eternal youth without further ado.

Will we be able to live in good health beyond 100?

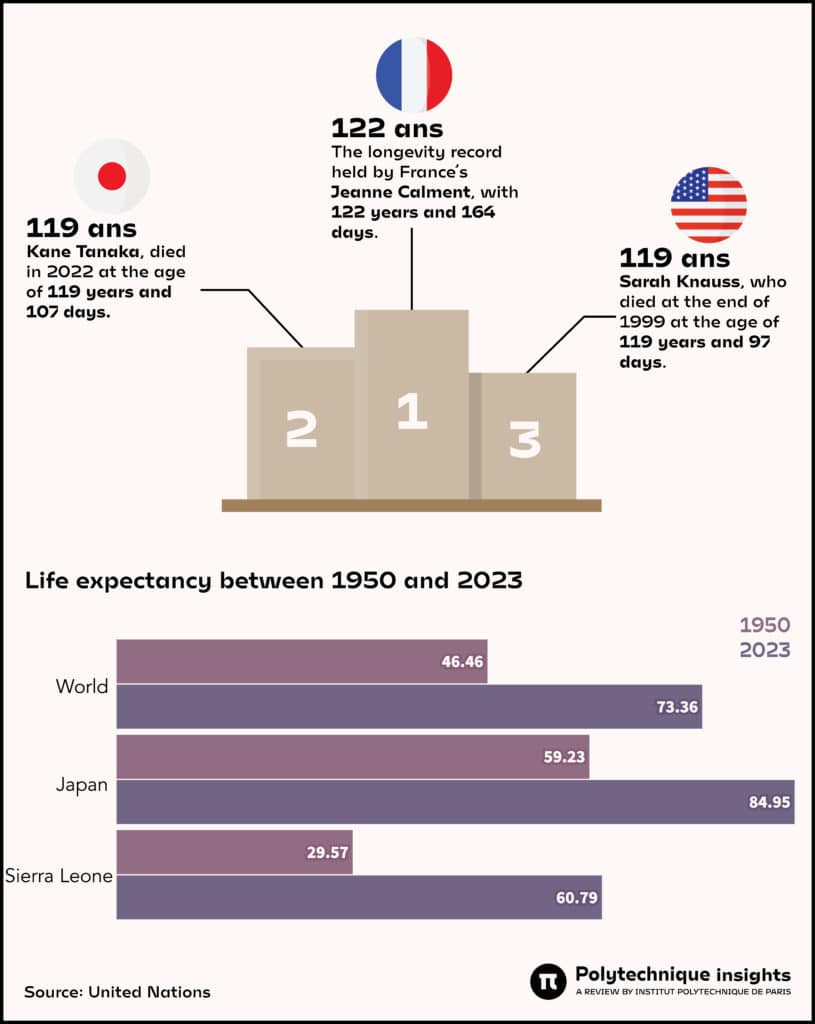

Growing at the rate of two years per decade, our life expectancy has already more than doubled. While it was only 27 years for a man and 28 years for a woman in 1750, it is now 80 and 86 years respectively in France3. To understand this spectacular phenomenon, it is important to note that there has been significant progress in the survival rates of children in the first few years after birth. More precisely, it is because we were able to combat infant mortality effectively through vaccination and hygiene measures under the leadership of Louis Pasteur, and then a little later through the use of antibiotics thanks to the discoveries of Alexander Fleming, that average life expectancy has increased. More recently, it is the age of death that has been the new target of researchers, with two objectives in mind: to improve the quality of life of older people, and to reduce the burden on health systems to maintain the economic and social stability of our ageing societies.

Controlling the ageing process means avoiding all the diseases that arise from the wear and tear of our organs.

However, the recipe is more complex than it seems. Controlling the ageing process or, to be more precise, preventing it from threatening the existence of individuals, means wanting to avoid all the diseases that arise from the wear and tear of our organs: neurodegenerative diseases for the brain, rheumatism for the joints, cardiovascular diseases for the heart, etc. If this objective were to be achieved, like Dorian Gray’s wish, we would remain eternal young people waiting for an accidental death to put an end to our existence. So, myth or reality?

The biology of ageing is a young science!

Many companies that see huge profits ahead are investing in laboratories that focus on the study of ageing. Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin made the fountain of youth their ultimate quest by creating Calico Life Sciences and Verily Life Sciences. More recently, Sam Altman (of Open.AI) has just invested $180 million in a company that is trying to delay death, and the Californian start-up Altos Lab has raised more than $3 billion by 2022 to reverse cellular ageing. This start-up even had the luxury of recruiting the 2012 Nobel Prize winner for Medicine, Professor Shinya Yamanaka4.

While it is easy to understand this craze, it is also easy to appreciate its consequences for all the players in the research field. Indeed, this new obsession is diverting attention from work previously dedicated to the treatment of age-related diseases to a better understanding of the mechanisms of ageing. Initiated in the 1990s, this research used simple organisms such as a small worm, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, or the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) as study models. While studying the survival mechanisms of the nematode exposed to difficult conditions, Gary Ruvkun discovered the existence of a lethargic phase called the “dauer stage”. This stasis allows the nematode to survive by slowing down its metabolism in a similar way to the mechanism that controls insulin secretion in humans.

At the same time, a molecular biologist, Cynthia Kenyon, managed to double the life expectancy of the same worm by mutating a gene that is also involved in the production of an insulin-like growth factor. Not surprisingly, this renowned researcher was subsequently recruited by Calico to become its vice-president. Since this early work, a multitude of studies have been developed by a growing community of scientists committed to extending the life span.

Treating ageing: a revolution in biological sciences?

Ageing is a succession of changes responsible for alterations that accumulate with age, but it must be distinguished from disease. Initially proposed in the 2010s, the biology of ageing distinguishes a list of characteristics including genome instability, progressive shortening of telomeres, epigenetic alterations, mitochondrial dysfunction, misregulation of protein folding, deregulation of nutrient sensing, cellular senescence, depletion of stem cell turnover and defects in intercellular communication. Since then, other markers have been added to the list, such as compromised autophagy, deregulation of splicing, a disturbed microbiome and more or less chronic inflammation. The addition of these new factors, at least for the last two, supports the idea of a holistic view of the human being according to which “the whole is more than the sum of its parts”5. We would only be a holobiont, i.e. an entity formed by different species that cohabit to form a single ecological entity. In other words, we would be the product, not only of our genes, but of a mutualistic symbiosis between us (the host) and our guests (the microbiome), and ageing would also depend on this fragile balance.

So how might the microbiome, or its mirror image as our immune system, contribute to the biology of ageing? We know that the immune system recognises hazards of all kinds through innate receptors that differentiate self from non-self. Microbial agents, cellular debris or nutrients interact with receptors that trigger the innate immune response known to reduce autophagy. The pathologies associated with ageing therefore correspond to this chronic state of autophagy dysregulation. This results in the accumulation of intracellular waste products and a chronic inflammatory response – a self-sustaining process that would lead to the decline of the organism.

There is another line of research that is currently very much in vogue: making ageing processes reversible. We now know how to reprogramme cells to make them younger, and my laboratory, along with others, has succeeded in demonstrating that brain ageing can be reversed by changing the blood composition of elderly subjects6. Today, we are able to reprogram molecular processes to rejuvenate nerve cells in the brain7. This research is already proving that organisms such as mice can gain more than a third of their life and maintain good mental and physical health.

Longer life expectancy, and afterwards?

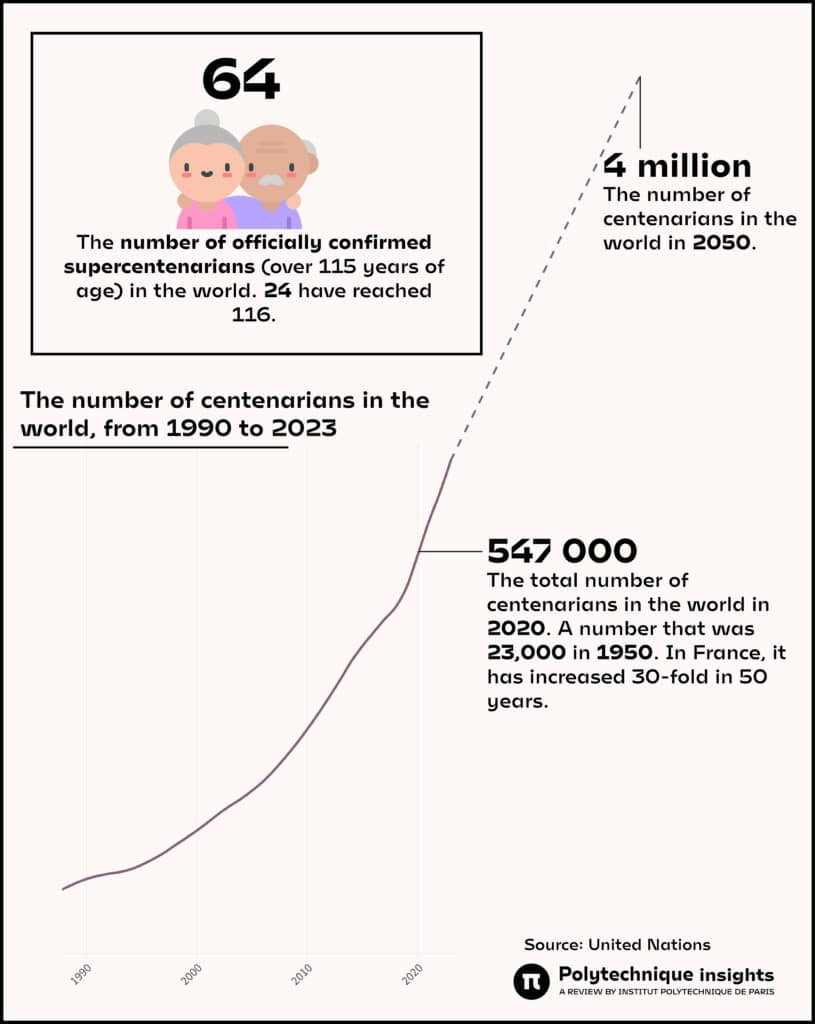

INSEE estimates that in France, at least 11% of children born after 2000 can expect to become centenarians or even ‘supercentenarians’. The number of centenarians has exploded since the 1960s: from 450 at the time, there are now almost 30 000, nearly 90% of whom are women. Demographers’ models predict that there could be thirteen times as many by 20608.

INSEE estimates that in France, at least 11% of children born after 2000 can expect to become centenarians or even supercentenarians.

In addition to these overly optimistic estimates, it should be remembered that life expectancy is not increasing uniformly across the planet. In France, it has increased only very slightly in recent years, while in the United States it is falling at a worrying rate9. Since the 1970s, progress in the prevention of cardiovascular disease has made it possible to significantly reduce mortality by reducing this type of disease, but today the margins of progress in this prevention are minimal. Their contribution to improving life expectancy is therefore becoming negligible.

If scientific progress can give us hope that one day we will no longer die of old age, then what will we die of? « To die of old age is a rare, singular and extraordinary death », wrote Michel de Montaigne in an essay on age10. As Montaigne thought, we would then only know accidental, brutal deaths or chosen deaths. In the latter case, death would not be the result of weariness with regard to suffering or illness – since they would no longer exist – but quite simply of boredom, depression, or spleen caused by the tireless and insipid repetition of days. After the scientific promise of eternal youth, are we condemned to assisted suicide?