Metagenomics: a new way to study biodiversity at the microscopic level

- Metagenomics is a technique that combines molecular biology and computer science to study the entire microbial world.

- Genomes can thus be analysed at the level of an entire sample to characterise complete ecosystems.

- A metagenomic study is carried out in two main stages: sample recovery and sequencing.

- Sequencing genomes requires a great deal of expertise in bioinformatics, which makes the development of metagenomics inseparable from the development of Big Data.

- Although metagenomics is costly and cumbersome to set up, it is nevertheless promising and allows us to discover a still unknown microscopic biodiversity.

Their small size makes it difficult to perceive, but micro-organisms are by far the most numerous entities on our planet. Bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi, and other tiny eukaryotes are present almost everywhere and form ecosystems that escape both our eyes and our test tubes, since it is estimated that only 1–2% of micro-organisms are easily cultivated in the laboratory. However, it is now possible to study the entire microbial world thanks to a technique that combines molecular biology and computer science: metagenomics.

Deconstructing genomes

As this term – coined in 19981 – indicates, the general idea is to analyse genomes at the level of an entire sample, contrary to the level of an individual or a species as was previously the case. This gives access to all the microorganisms it contains, including those that we do not know how to grow in culture, and to characterise complete ecosystems. However, although recent technological advances have made metagenomics a fast-growing approach, its implementation remains complex.

Let’s take a step back to put things in perspective. The first genome to be sequenced, in 1977, was that of a bacteriophage virus, which measured about 5,300 nucleotides2. Bacteria3 and yeast4 followed, and finally the human genome: published in the early 2000s, it took hundreds of millions of euros and years of work to decipher most of its 3 billion nucleotides5. The first truly complete sequence of a human genome was only published in April 20226!

Sequencing is therefore a relatively recent technique that is constantly improving… So much so that it is now possible to sequence a human genome with satisfactory quality for only €1,000, in a single day. There are in fact different so-called ‘next-generation’ sequencing techniques, varying in accuracy, speed and cost, and it is now possible to recover millions or even billions of sequences in parallel to analyse tens of billions of nucleotides every day. This is the first technological advance that allows the simultaneous study of the genomes of communities of micro-organisms… But it is not the only one.

In fact, sequencing many nucleotides leads to the recovery of a lot of digital data, which must then be processed. The development of metagenomics is therefore taking place in parallel with that of “Big Data”. Storage, calculation capacities, development of tools or database management: making genomes talk requires equipment and solid skills in bioinformatics.

Metagenomics is therefore at the crossroads of two rapidly evolving fields, and its potential continues to increase. It may be tempting to see it as the new Holy Grail of microbiology, allowing us to discover a microscopic world that has so far eluded us. However, this approach remains cumbersome, costly, and fraught with pitfalls. Before using it, it is best to have a well-defined question to answer and to refine the protocol to avoid being buried under a heap of unusable data.

Metagenomics step-by-step

The first step in a metagenomic study is to collect samples. Whether we are interested in the micro-organisms found in soil, water or human microbiota, we need to work on samples that are adapted to the question we are asking, that are comparable (the composition of the soil will not be the same in different places, at different depths or during different seasons, for example), that are sufficiently numerous and diverse to be representative, and that are sufficiently large to be able to recover the quantities of DNA necessary for the rest of the protocol.

Different processes can be used for this extraction, the protocol of which is optimised according to the medium of origin, the types of organisms of interest and the material to be recovered. In fact, the preparation of the sample is the opportunity to sort the organisms studied (for example by filtering to keep only those of a certain size) and to select the type of nucleic acids that will be sequenced later. In particular, it is possible to purify messenger RNA (mRNA) rather than genomic DNA to analyse the actual activity of a microbial community: this is known as metatranscriptomics rather than metagenomics.

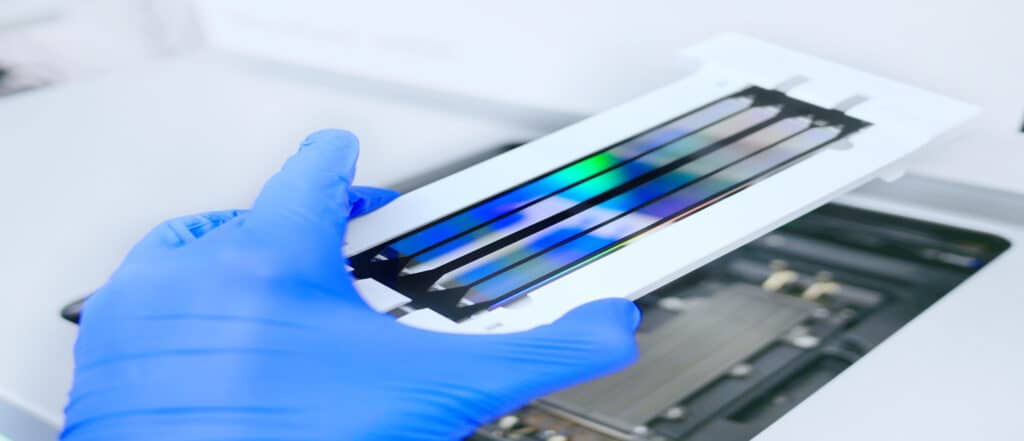

Next comes the sequencing stage, with two possible approaches: targeted or global metagenomics. Targeted metagenomics is mainly used to identify and classify the species present in a sample. In this case, only certain parts of the genomes, considered specific to a particular type of organism or range of functions, are amplified, sequenced, and analysed. Global metagenomics, on the other hand, enables the fine characterisation of communities of micro-organisms, but is more cumbersome to implement. It consists of recovering all the DNA contained in a sample, fragmenting it to obtain pieces short enough to be sequenced, sequencing all these portions of genomes, and then reconstructing the original genomes as best as possible.

It is like taking several jigsaw puzzles, shuffling all the pieces and then trying to put each puzzle back together.

This is like taking several jigsaw puzzles, shuffling all the pieces (with some loss) and then trying to put each puzzle back together from this disparate pile. For organisms whose genomes are already recorded, this is relatively easy because we have models to follow. It is more difficult for unknown organisms, which may represent 90% of some samples7. Tricks have been devised to make it easier to solve this puzzle8 [pi_noteBy combining different metagenomic datasets to search for fragments with comparable copy numbers: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111155/[/pi_note], but most of the microscopic biodiversity is still unknown to us: metagenomics is just beginning to clear it by measuring the extent of our ignorance.

Metagenomics and bioprospecting

However, this approach is not only descriptive, but it also opens up new possibilities for identifying active microbial compounds. Indeed, after fragmentation of the genomes present in a sample, we can produce bacteria each containing one of the pieces of DNA obtained and see if any of them acquire interesting properties (recovering such and such a strain of energy, degrading such and such compounds, having antibiotic activity, etc.). All this without growing cultures, or even identifying, the organisms that possessed this skill in the first place!

Beyond fundamental research, the functional side of metagenomics therefore broadens the field of bioprospecting. This is still metagenomics, which is costly and cumbersome to set up… But it will develop as technology advances. The existence of direct applications in fields as fundamental as medicine and agronomy is another reason to follow the progress of metagenomics and the associated discoveries in the years to come.