How do our bodies tune into the Sun’s rhythm?

- More than one in five people in France are thought to suffer from chronic sleep disorders, whereas our great-grandparents had fewer problems sleeping.

- Daily exposure to natural light helps to synchronise our cycle by adapting it to the day/night cycle; without light, our body would be in danger.

- A study of blind people showed that they suffered more from sleep disorders, but also from digestive problems and anxiety.

- A study of RATP employees shows that tram and bus drivers (outdoors) have fewer sleep disorders than metro drivers (indoors).

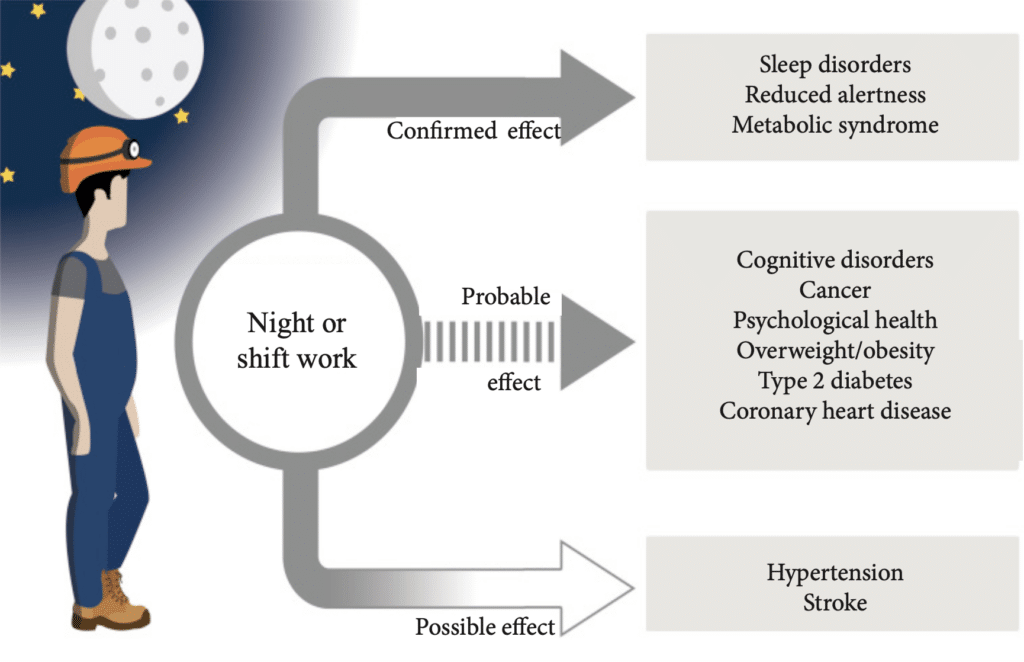

- Night work is also thought to have harmful effects on all the major functions of our body, with increased risks of health problems.

It’s not easy to enjoy a good night’s rest: more than one in five people in France are said to suffer from chronic sleep disorders. Yet, “our great-grandparents had much fewer problems sleeping,” says Claude Gronfier, a chronobiology researcher at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) at the Neuroscience Research Centre in Lyon. Could it be because they spent their days working outside? Perhaps.

A clock programmed into our genes

Since the 1970s and the discovery of the first “clock gene”, we have known that our bodies are set to the 24-hour day right down to the deepest level of our DNA. “It is a finely tuned self-regulating mechanism of molecular loops,” explains the neurobiologist, who is also president of the Société Francophone de Chronobiologie. A gene codes for a protein, which accumulates in the cytoplasm of the cell, before it enters the nucleus to inhibit the expression of the original gene until it disappears. Then the cycle begins again.

“Since then, we have discovered about fifteen of these ‘clock genes’: TIM, CLOCK, BMAL, REVERB, PER 1, PER 2, PER 3, CRY, etc. Some act as brakes, others as accelerators of the clock,” explains Claude Gronfier. This internal clock is expressed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus located at the base of our brain, following the unchanging rhythm of approximately 24 hours… and 10 minutes on average in humans. A slight delay corrected by our retinas! Daily exposure to natural light synchronises our circadian cycle, adapting it to the alternation of day and night. Without light, our entire body is in danger.

Free-running clock

The case of the visually impaired1, studied in the 2000s, sheds light on the consequences of a “free-running” clock, i.e. one that is unable to synchronise itself. “Take the example of a blind person’s internal clock of 24 hours and 30 minutes. Their bedtime will be perfectly synchronised with the real time only every 48 days. In these situations, general practitioners find themselves making long-term prescriptions for these people who suffer from sleep disorders, of course, but also from digestive problems, drowsiness, insomnia, or anxiety,” explains Claude Gronfier.

A generalised disruption of the body that can be explained by the presence of clock genes well beyond our brain. “They are found in all our tissues: lungs, heart, liver, muscles, adipose tissue, etc.” Thus, the “internal clock” has now given way to the term “circadian system” (editor’s note: circa: close to; diem: day), which is better able to encompass all the processes involved in the wake and sleep cycle. “These peripheral systems allow for fine-tuning of the circadian rhythm at a local level” the researcher explains. A genetic mechanism (between 8 and 20% of the genome) that is thus expressed in rhythm, orchestrated by the central circadian clock, the only one capable of synchronising with natural light. A necessity that goes against our current lifestyles.

Between 10,000 and 100,000 lux

“It’s barely 100 years since we first started living indoors,” recalls Claude Gronfier. Although the chronobiologist has taken care to position his office near a large bay window, he points out that this is not enough. “When facing a window, there should be around 300 to 1,000 lux [Editor’s note: lux is the unit of measurement for illuminance]. However, our species evolved outside! We developed in sunlight, which reaches levels of 10,000 to 100,000 lux during the day.”

Could our sleep disorders be linked to this lack of light exposure? In any case, that is what a 2011 study3 by Damien Léger, head of the Centre du sommeil et de la vigilance de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Paris, suggested about RATP employees. By comparing the quality of sleep among bus and tram drivers – who drive outside – and that of their counterparts confined to the metro, the researcher and his team observed a higher prevalence of sleep disorders (insomnia, daytime sleepiness, hypersomnia) among the latter. Other studies carried out since then confirm the major role played by natural light in our good health. This naturally raises the question of night work. Beyond shifting rest hours, does almost no exposure to daylight have a lasting impact on health?

An end to night work

While the repercussions of night work4 on sleep duration and quality are well established, the latest studies also point to potential harmful effects on all the major functions of our body. “It is not surprising, given the vital role of the circadian system in the body, that these workers are at higher risk of health problems,” says Claude Gronfier. In a study he led with ANSES, the researcher signed a report in 20165 with a group of 19 experts on the health consequences of shift work (editor’s note: work where teams take turns at the same station at set times). In particular, it shows a higher prevalence of sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, stroke, obesity, diabetes, breast cancer, an increase in cognitive disorders and the occurrence of cardiovascular problems. These consequences are certainly underestimated, as they are not well known by shift workers themselves, who nevertheless represent 20% of employees in France.

“One might think that we end up adapting to night work by becoming nocturnal animals, but this ignores the fact that with every holiday, every weekend, every social occasion, we are once again exposed to sunlight, which resynchronises us to working by day and sleeping by night. We are diurnal animals and not made for night work,” concludes the researcher.