In January 2025, violent wildfires hit the Los Angeles region. Initial analyses1 show that the aridity and heat of the previous months are among the factors behind the intensity of these fires2: they contributed to drying out the vegetation – which was particularly dense because of the previous year’s rainfall – and increasing the amount of fuel available. “In recent years, the drying out of the environment has globally increased the length of the fire season across much of the world, contributing to forest fires of unprecedented severity,” points out the IPCC in its 6th assessment report3. Drought is a major natural hazard. Between 1970 and 2019, only 7% of natural disasters were drought related. Yet they contributed disproportionately to 34% of disaster-related deaths, mainly in Africa, as summarised by the IPCC4. In the United States, droughts cost $250bn and killed nearly 3,000 people between 1980 and 20205.

Climate change increases the severity of droughts

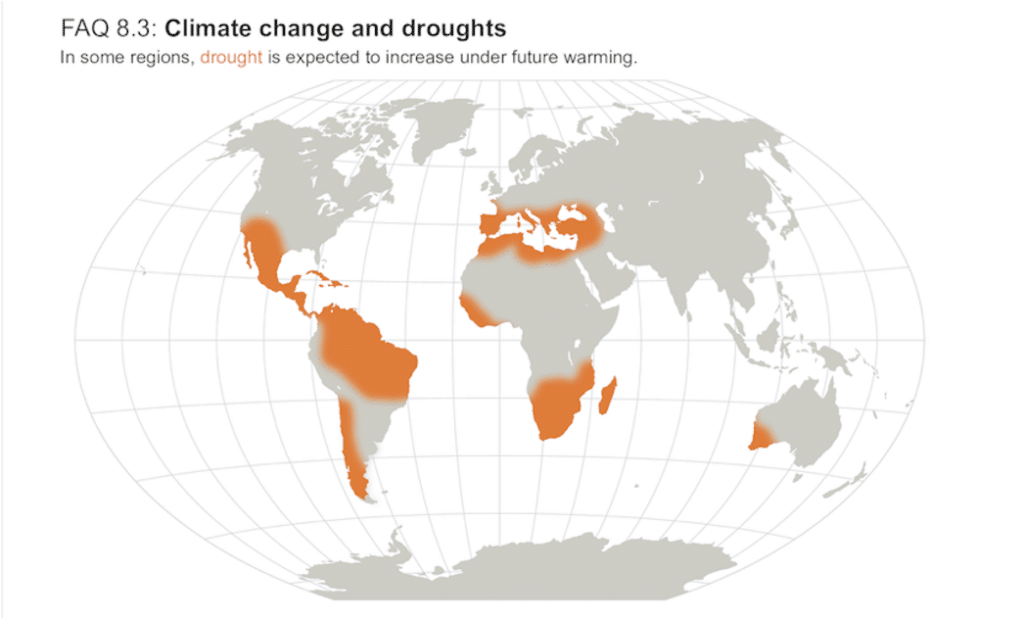

Attribution studies, which establish the impact of climate change on extreme events, have already shown on numerous occasions the contribution of climate change to the frequency or severity of droughts. Of course, not all droughts can be explained by climate change, and droughts occurred even before the climate was modified by human activities. But of the 103 droughts studied to date (summarised by Carbon Brief6), 71 have been made more severe or likely by climate change. The group behind these attribution studies, the World Weather Attribution, summarises7: “We can attribute an increase in the severity and likelihood of droughts in the Mediterranean, South Africa, Central and East Asia, southern Australia and western North America to global warming with a high degree of confidence.”

To better understand how climate change is influencing droughts, let’s take a step back. What exactly are we talking about? “There is no universal criterion for what constitutes a drought,” notes researcher Toby R. Ault in an article Ault8. In the broadest sense, droughts are defined by a lack of water, or drier-than-normal conditions in a given location, which can vary in duration. “Meteorological droughts are marked by a deficit in rainfall (of varying duration); they can also be hydrological, with reduced levels in rivers or water tables (sometimes for several years), and agricultural, with soil drought having a potential impact on crops and natural vegetation,” explains Hervé Douville. Most droughts begin with a lack of rainfall (a meteorological drought) and can develop into agricultural and hydrological droughts9. Vegetation and human activities, such as irrigation and soil artificialisation, can increase or decrease the severity of drought and its socio-economic impact.

Human activities also have an indirect impact on drought. Climate change is one such factor. Climate change is intensifying the water cycle, as we have already explained in previous articles. As the atmosphere warms, its maximum water content increases by an average of 7% for each degree of warming.

The impact of global warming on droughts

This has several implications when it comes to droughts. Firstly, precipitation is changing: its seasonality and intensity are changing. “In Europe, for example, climate change is leading to a reduction in the number of rainy days and an increase in extreme rainfall,” explains Hervé Douville. This less frequent but more intense rain causes more surface run-off and is generally less effective at recharging the water tables. Rising global temperatures are also reducing snow stocks in some regions, affecting the flow of rivers fed by spring snowmelt. Finally, in the 6th Synthesis Report, the IPCC states that subtropical regions will also experience a significant drop in annual precipitation – this impacts the Mediterranean, South Africa, south-west Australia and South America, Central America, West Africa and the Amazon basin.

“In addition to rainfall, climate change is also increasing surface evapotranspiration, which is making a major contribution to agricultural drought,” points out Hervé Douville. On the continents, evapotranspiration refers to the flow of water that evaporates from the soil and the surface of rivers or lakes, but also to the transfer of water from the soil to the atmosphere via plant transpiration. However, the warming of surface temperatures is greater over the continents than over the oceans. As a result, more energy is available for water to evaporate, and the severity of droughts increases. This effect is partly offset by the effects of CO2 on plants, which can increase their efficiency in using water from the soil. But this is not enough: evapotranspiration has increased since the 1980s.

Regional effects vary

The effects of these phenomena linked to global warming vary from region to region. While meteorological droughts have so far been relatively unaffected by climate change, there has been an increase in agricultural droughts throughout the world – only northern Australia has been spared10. This underlines the major impact of increased evapotranspiration on droughts, which the IPCC points out is very likely to be due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. A clear link has even been established between warming linked to human activities and an increase in the frequency and severity of droughts over recent decades in the Mediterranean, western North America and south-west Australia.

In the future, these effects will increase as average global temperatures continue to rise. Depending on greenhouse gas emission scenarios, the duration of droughts could be 0.5–1 months to 2 months longer than today in Central America, the Mediterranean, the Amazon basin, south-western South America, western North Africa, southern Africa and south-western Australia. “All these regions will become drier as a result of reduced precipitation and increased evapotranspiration […] even for low greenhouse gas emission scenarios,” summarises the IPCC. Without a drastic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, around a third of the world’s land area is likely to suffer at best moderate drought by 2100. Only a few regions and seasons should see their risk of drought decrease: high latitude areas in North America and Asia, and the monsoon season in South Asia.

This will have major socio-economic consequences. In a study published in 202111, a team estimated that, in the absence of climate action, drought-related damage could rise from $9–65bn each year in the European Union and the United Kingdom. “The impact of floods and droughts is expected to increase in all economic sectors, from agriculture to energy production, with negative consequences for global production of goods and services, industrial production, employment, trade and household consumption,” summarises the IPCC. By reducing our greenhouse gas emissions and implementing adaptation measures, we can significantly limit the impact on our communities.