Giant viruses, enigmatic microscopic behemoths you should know about

- In 2003, researchers thought they were examining a bacterium under a microscope before realising that it was a very large virus, called "mimivirus".

- Mimivirus is 0.7 µm, three times longer than the known length of viruses at the time, which is 0.2 µm.

- Many cousins of mimivirus were quickly discovered, as well as pandoravirus, pithovirus and other molliviruses.

- Metagenomics has made it possible to discover these giant viruses, of which there are thousands.

- Many questions remain unanswered, especially concerning the genomes of the giant viruses, the content of which bears no resemblance to anything we have ever known.

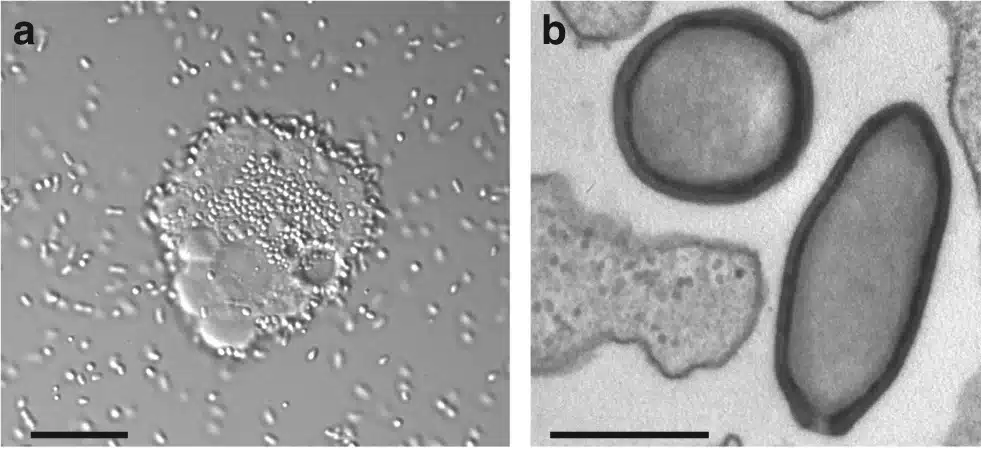

In 1992, an epidemic of legionnaire’s disease hit the English city of Bradford and completely changed virology forever, even though this disease is caused by bacteria! Those of the Legionella genus, which live in warm water and usually multiply at the expense of amoebas (small organisms composed of a single cell, whose functioning is closer to that of our own cells than to that of bacteria).

A French discovery from England

One of the distinguishing features of Legionnaires’ disease is that it is not transmitted directly from human to human, but via aerosols from environments contaminated by the bacteria. To identify the origin of the Bradford epidemic, microbiologist Timothy Rowbotham took a few samples in search of the famous Legionella and the amoebae they parasitise.

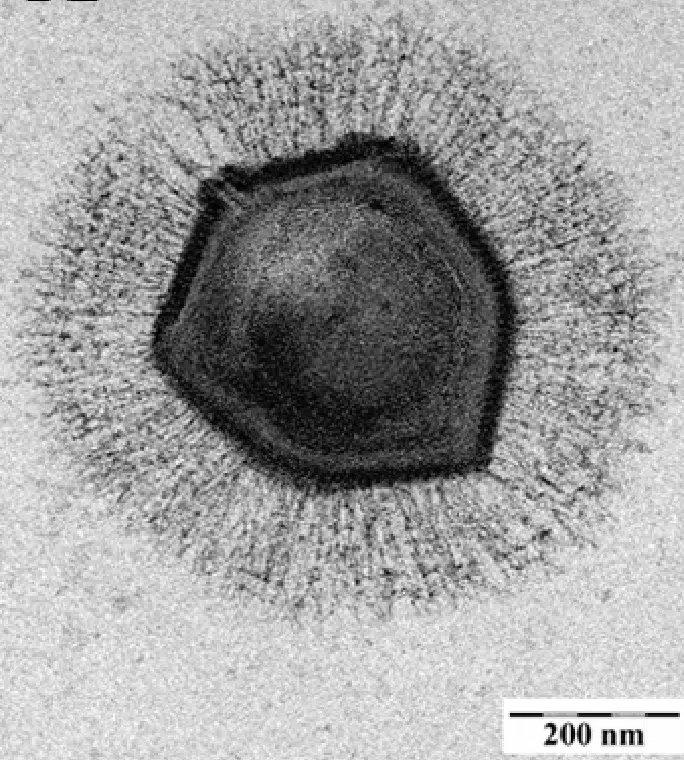

Looking under a light microscope at a sample recovered from the hospital’s cooling tower, Rowbotham found that it did indeed contain amoebae, which in turn contained what looked like bacteria… but whose shape did not match that of Legionella. He named this new microbe “Bradford coccus” and tried to characterise it with tools adapted to the study of bacteria for several years. But to no avail.

The sample was returned to a freezer and then, in 1995, the young researcher Richard Birtles, leaving to do a post-doctorate in Marseille, took some of it with him1. At first, the French researchers did no better than the English: it was impossible to characterise the genome of Bradford coccus… Until someone had the idea of observing this so-called bacterium with an electron microscope, which had sufficient magnification power to realise that it was in fact a virus, of astonishing size.

A few years later, three research teams from Marseille shared their results in a paper entitled “A giant amoeba virus”2. Timothy Rowbotham had unknowingly isolated a virus capable of infecting amoebas and measuring about 0.7 µm in diameter. In honour of its initial confusion with a bacterium, it was named mimivirus, literally “microbe-mimicking”.

Giant viruses, a major discovery

The description of this virus in 2003 was revolutionary! It took years to understand the true nature of mimiviruses as nobody at the time thought that such large viruses could exist. And with good reason. At the end of the 19th Century, the ability of viruses to pass through the pores of filters fine enough to retain bacteria was one of the first characteristics that allowed them to be identified as a new type of infectious agent. In other words, viruses had always been defined as being smaller than bacteria, which are on average 1 µm in length, but were considered to be up to about 0.2 µm in size. This is three times smaller than the size of mimiviruses.

However, this microscopic colossus is not an exception and the discoveries of giant viruses have followed one after the other since 2003, notably thanks to the work of the Genomic and Structural Information laboratory, now directed by Chantal Abergel4. Many relatives of mimiviruses are now known, grouped together in the Mimiviridae family. As well as pandoraviruses, pithoviruses and other molliviruses: as is often the case in biology, the more we look for giant viruses, the more we find them!

Some of these discoveries are real achievements: pithoviruses5 and molliviruses6 were initially isolated from permafrost that was about 30 000 years old. This has not prevented them, in the expert hands of researchers, from still being able to infect amoebas. To show that this is not so unusual, the same team recently published a preprint in which they revived no less than 13 different amoeba viruses in the same way7.

Family portrait

Although the first giant viruses were identified by co-culturing with hosts susceptible to infection (mainly amoebae), over the past ten years a new tool has accelerated the pace of discovery: metagenomics. This technique, which combines massive sequencing and bioinformatics analyses, has led to an explosion in the number of known giant viruses that now number in the thousands8.

They are particularly numerous in the ocean, but they are also found in soils and lakes. And it is clear that we are only just beginning to understand the quantity, distribution and diversity of these viruses. If one were to sketch a family portrait, all known giant viruses have genomes composed of double-stranded DNA and most of them form viral factories in the cells they infect, which are exactly what their name describes. Their size can reach up to 2 µm in length for tupanviruses, a member of the Mimiviridae9 and their genomes measure up to 2.5 million base pairs for pandoraviruses10.

It is not clear which organisms are naturally infected with giant viruses, especially when they are identified by metagenomics. Different approaches, such as searching for genomes that are systematically associated with viruses in samples, suggest that giant viruses can infect a large number of eukaryotic microorganisms, not just amoebae12. The list is far from definitive at present, but the longer it goes on, the more likely it is that these viruses will have significant impacts on ecosystems.

Many unresolved questions

Of all the things we have yet to discover and understand about giant viruses, it is their genomes that probably raise the most questions. Not only are they disproportionately long (for viruses), but their content is astonishing. Firstly, because a large proportion of the genes (sometimes more than 90%!13) often don’t resemble anything known to us. It is impossible to know where they come from or what they are used for. Secondly, because some of the genes that we do understand have never been observed in viruses before.

Indeed, giant viruses have genes involved in cellular processes, such as DNA replication or the expression of genetic information. They are far from being autonomous, but this still raises questions about their degree of dependence, their origin, and their evolutionary history14. In 2008, the identification of viruses capable of infecting giant viruses that were themselves infecting an amoeba added another piece to this puzzle15.

Unknown only twenty years ago, giant viruses are regularly the subject of new discoveries and each one raises its own set of questions. With many in the oceans and interacting with micro-organisms that play key roles in oxygen production or atmospheric CO2 capture, they may not be heard of outside virology journals. But beyond their potential impact, they are fascinating in that they make us rethink how we define terms like ‘virus’ and ‘living’.