How to monitor climate change from space

Following the COP26 in Glasgow, there has been much talk about how to monitor climate change around the world and its effects. In the Dynamic Meteorology Laboratory (LMD), we focus on Earth observations using satellites to improve our understanding of our planet’s climate and changes that are happening. This is possible mainly thanks to progress in satellite technology, and our ability to analyse the data gathered.

Watching Earth from the skies

We have two objectives when we observe the Earth from outer orbit. First, we aim to understand the planet as a whole, asking fundamental questions like: how did Earth become to be the way it is now? How is it evolving? But we are also looking at key criteria that hold answers to some of today’s biggest societal issues, such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (many of which are climate related)1 or understanding risks of hurricanes, earthquakes and other natural disasters.

Efforts are global, with different States around the world turning their focus to various technical areas. In France, at the National Centre for Space Studies (CNES), NASA was our top partner for a long time along with the European Space Agency (ESA). But in recent years we have seen some big changes in the Earth Observation sector. Collaborations with India, China and other smaller European agencies in Germany and the UK have swelled. And, with the advent of nanosatellites [tiny, lightweight satellites designed for highly specific missions] dozens of new, smaller space agencies have been created around the world working on diverse projects – so many that we struggle to keep up with all of them!

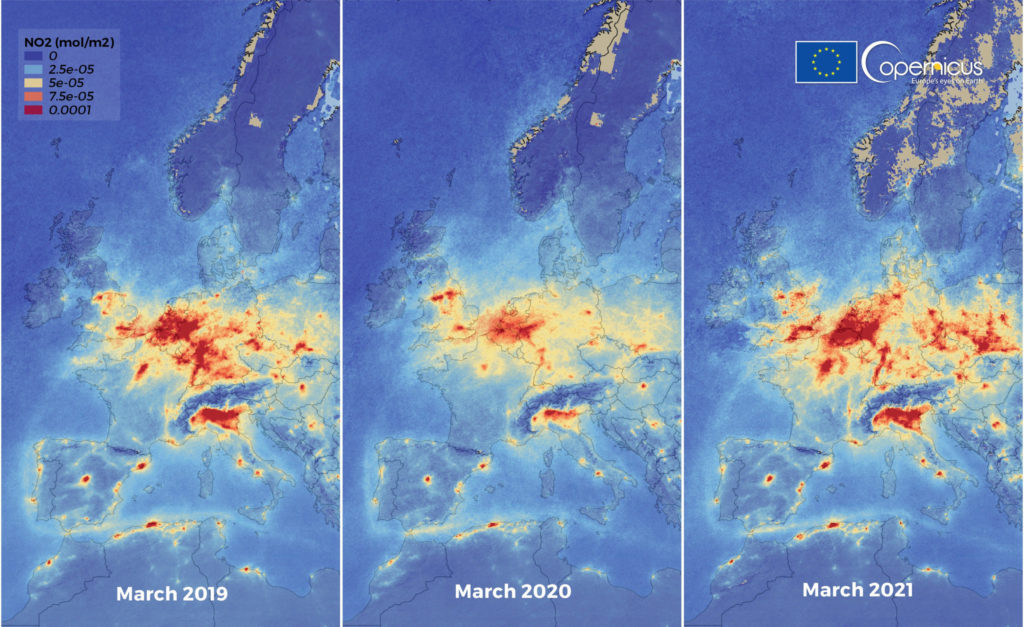

Moreover, the field has received both public and political recognition – especially thanks to the COP21 in 2015 that saw the selection of 2 French space programs dedicated to the monitoring of CO2 and CH4: MicroCarb2 and Merlin3, respectively. Add to that the other game-changer for us: the European Space programme, Copernicus4. Operational since 2014, it comprises now 8 satellites (known as Sentinels) in orbit around the globe, each observing different compartments of the Earth system. Another 10 are in preparation for continuous launches up to 2030 and we are already planning the next programme with at least 6 more!

The programme is dedicated to providing autonomous and independent access to information in the domains of environment and security on a global level in order to help service providers, public authorities and other international organisations. All Copernicus data is also open source. This means it is free to access for agencies, laboratories or other entities around the world who may wish to use it (including commercial enterprises). And one of its bigger users is the scientific community.

Technological innovation for new capabilities

In France, we have three fields of excellence, which allow us to study precise changes in so-called essential climate variables, a set of 54 geophysical variables that critically contribute to the characterisation of Earth’s climate, of which about 60% can be addressed only by satellite data: altimetry, optical imagery and atmospheric sounding.

Using altimetry, from the pioneering missions TOPEX/Poseidon, Jason and now Sentinel‑6, we can monitor sea water levels over time, a hugely important factor in global climate change. Our system can keep track of ocean depth changes and is able to see the 3.3 mm annual increase, which has driven the 10 cm rise in sea levels over the last 30 years!

Optical imagery allows us to follow what’s happening on Earth with extreme spatial resolution (up to 10 metres). Using this technique, missions like TRISHNA allow us to analyse ground humidity and follow crop harvests from the skies as a way of keeping track of human-driven changes to the planet’s surface5.

Finally, atmospheric sounders let us measure radiation coming from various layers of the atmosphere across the whole light spectrum – even that which we cannot see – to offer indications for the presence of greenhouse gases and other major pollutants. These measures are key to understanding the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere and, more importantly, how it is changing over time due to human activity. The IASI instrument developed by CNES in cooperation with the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT)67 has recently provided a unique view on the transport all around the world of carbon monoxide emitted by dramatic Californian fires and allowed tracking several desert storms responsible for “yellow sky” in Europe.

Data treatment back on land

Satellites take various measures or images from the upper atmosphere, yet most of the data is analysed on the ground. However, it is very rare that we can directly measure exactly what we need. Hence, to make sense of satellite measurements we need to interpret them in terms of geophysical information by designing innovative algorithms, such as machine learning, capable of transforming data into useful information. Moreover, to be useful and add information to the one already provided by ground-based observation networks, we need to reach a high level of accuracy. For instance, to isolate the very small signatures of climate change, we need to be able to detect a small trend of 0.1 K annual increase… from measurements made at 800 km from the surface!

Another challenge is to create an integrated observation system that can combine space data with measures from the surface or in the air [such as weather balloons or research aicrafts] in an integrated observation system. Our goal: to link these observations together in order to generate meaning – and for that we need accurate measurements and numerical models of the Earth system to assimilate them.

Planning the next step

What we need for the coming years is innovation… and more continuity in space missions. Innovation to observe new geophysical variables, such as cloud convection, and to improve the observations: to allow studying low-scale processes, it is needed to increase the spatial resolution from 10 to 2 m in cartography or from 75 to 15 km in altimetry. Continuity to monitor global change: if we consider climate studies, it takes at least 20 years to see trends in the data. Back in the 1950s missions lasted only 5 years. Whereas, these days, we are now closer to 12 years. Even so, we still need more permanency, coupled with the capacity to link data from one platform to another: this is key if we wish to make long-standing comparisons in climate data year on year. As such, we need long-term programs with long-term budgets.

And this is challenging also from a management point of view! For instance, the IASI mission was designed from the start to last 20 years, by building three satellites before 2006, of which one was launched straight away and the other two were kept in storage for 4–8 years. In that time technology can change and engineers move on or retire, taking the skills and competencies away with them. We are already planning another three missions for launch in 2023, 2030 and 2037. So, we need to be able to hold onto our engineers and assure that the satellites age well whilst they wait in the hangar for over a decade before they are launched!