Invisibility is just around the corner

- In their quest for invisibility, researchers have developed “metamaterials”.

- These are objects with multiple microscopic details capable of deflecting a wave from its path, thus preventing it from being reflected on a targeted object.

- The concept of invisibility applies to any type of wave, making an object “invisible” to a wave protects it from its various effects.

- As such, this concept can have many real-world applications such as making submarines invisible to sonar, protecting ports from sea waves, developing an anti-earthquake city and, perhaps allowing a person to become invisible.

Theoretically, if an object does not reflect a wave, then it is invisible to it. This applies to all types of waves, whether electromagnetic – such as visible light, for example – acoustic or seismic. However, in practice, many technical challenges remain, which still prevent us from achieving complete invisibility.

In their quest for invisibility – and in the absence of Harry Potter magic – researchers have used their knowledge of physics to develop metamaterials, which are structures with microscopic details that can be specified by the user depending on the desired application. The multitude of these details have the effect of trapping a target wave passing through, making it either resonate until it uses up all its energy, or deflect it to avoid reflecting off the target object. Thus, rendering the object invisible. Kim Pham, lecturer at the Mechanics Unit of ENSTA Paris, is working on this subject that spreads out to various applications.

#1 Acoustic waves:

Becoming invisible to sonar

Nature has given us an interesting lead in the form of whales, and more precisely one of their hunting techniques. To hunt, they sometimes release a wall of bubbles inside which they make sounds. The wall of bubbles trap acoustic waves within it, causing them to resonate, thus stunning fish trapped inside. Whereas, from the outside, the sound is almost imperceptible. This principle is explained by Minneart resonance, and the effect of the density contrast between air and water. A microscopic bubble can resonate wavelengths a hundred times greater than itself and relies on the multitude of bubbles. The result is a wall quite similar to metamaterials. As such, this example offers an insight into how acoustic waves can be controlled through the concept of invisibility.

During the Second World War, the Germans had already developed a similar defence technique for their submarines by lining their external surface with anechoic tiles. Kim Pham, for example, is working on these tiles to better understand their mathematical logic and improve their effects. Composed of multiple cavities, they render the submarine undetectable to sonar waves, provided that the cavities are adjusted to the right frequency.

#2 Maritime ripples:

Protecting ports from waves

Another useful application is the protection of harbours from undulatory movements of the sea, especially from swell. The aim is to calm the sea surface of the harbour. It is technique already exists, using large concrete blocks, however they aren’t very ecological. To remedy this, Kim Pham and his team are proposing a floating resonance belt1, which will surround the port to be protected. Even if these prototypes are made of plexiglass, the choice of material is not yet decisive: the important thing is that it is light and resistant. Inside is a small cavity that allows the waves of the swell to pass through it, becoming trapped inside. One there, they resonate within it until they are exhausted.

Below: the cavity of the belt has been closed. The floating belt is therefore just a non-resonant obstacle and the swell can pass through it. (Video courtesy of Léo-Paul Euvé)

The innovation is therefore in the lightness of the mechanism, which floats. But also, in its ease of installation and movement. Hence, such concepts could be used on a large scale and potentially introduced as a way to protect against more violent sea waves such as tsunamis.

#3 Seismic waves:

Redirecting earthquakes into the ground

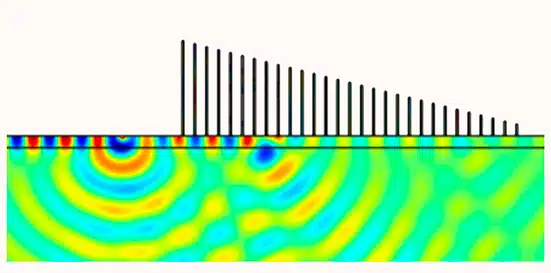

The concept of invisibility is also applicable to seismic waves. The two main types of seismic waves are surface waves and volume waves. The first type, surface waves, can cause serious damage to the Earth’s surface. The second type, volume waves, propagate underground, so their impact on the surface is limited. Kim Pham’s team has discovered that, if a number of conditions are met, the trees in a forest can act on surface waves (known as Love waves) by transforming them into volume waves, and thus sending them deep into the ground, reducing potential damage2. This concept uses the same principles as those of metamaterials. It is the multitude of trees in the forest that allows the wave to be controlled and deflected. It has come to be known as metaforesting, where main innovation is the progressive decrease in height of each tree in the path of the surface wave.

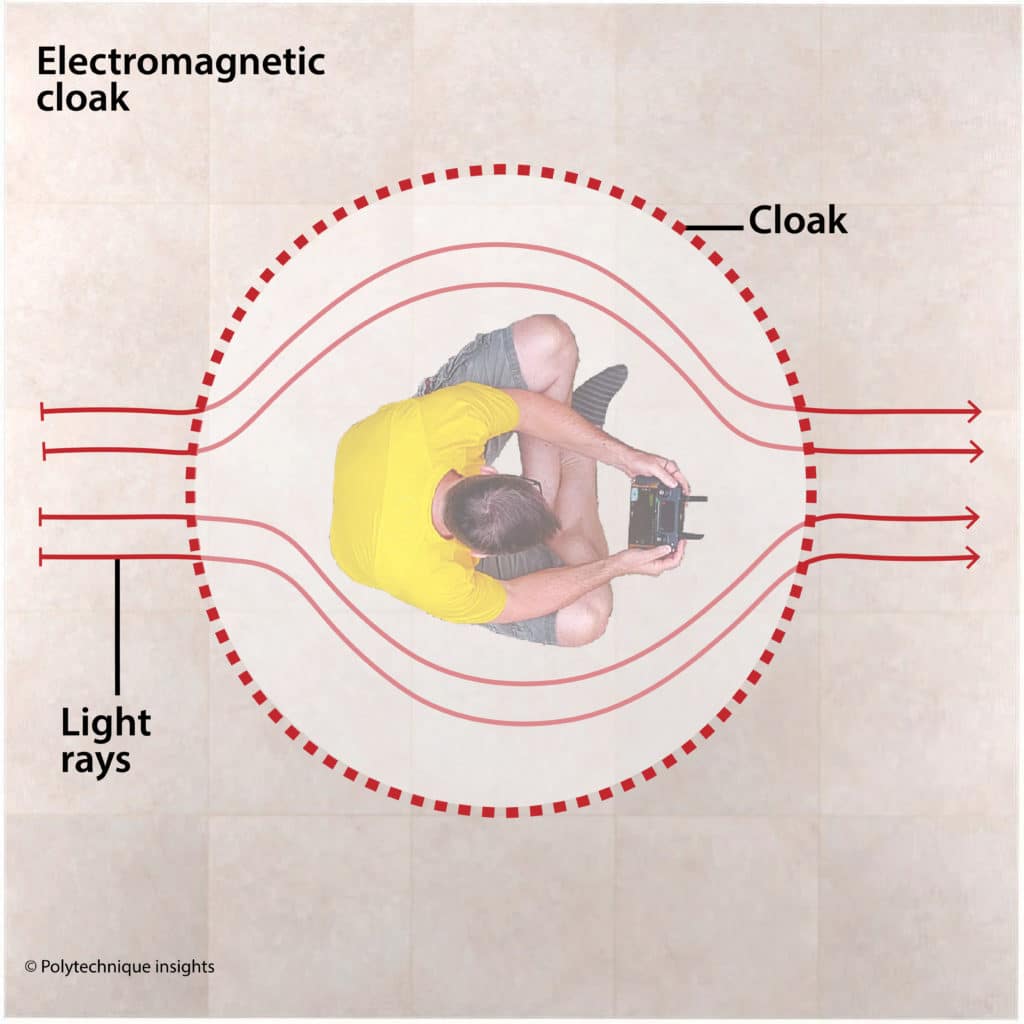

The more this wave passes through the forest, the more it will be redirected towards the ground, to the point of plunging into the Earth’s depths, and thus becoming a volume wave. This type of discovery allows us to imagine many useful applications, in particular the development of cities of the future, built with the same principles as these metaforests3 in the construction of buildings. For example, an anti-earthquake city could be created, that resembles the now famous prototype of the invisibility cloak4 proposed by Sébastien Guenneau (a CNRS Researcher at Institut Fresnel).

#4 Light rays:

Making an object invisible

Since visible light is made up of electromagnetic waves, this concept could theoretically make any object invisible to the naked eye. We perceive a visible object because light reflects off it – it is the reason why we cannot see anything in the dark. If the light waves can be deflected, and thus prevented from reflecting off the object in question, then it will be invisible. Based on this principle, the researcher John Pendry succeeded in developing a prototype invisibility cloak (this time for visual light waves)5, which earned him the Isaac Newton Medal from the UK Institute of Physics in 2013.

However, the spectrum of light visible waves is between 380 and 780 nanometres (nm). Therein lies the technical challenges. First, in the microscopic scale of the cavity of the metamaterial used for this purpose, which must be sub-wavelength – that is, smaller than the targeted wave, (a few hundred nm). Second, in the diversity of colours, each having a specific wavelength ranging, for example, from 780–622 nm for red light and from 455–390 nm for violet. Real objects are rarely monochrome, so to make it invisible, a metamaterial with diverse cavities, specific to the wavelength of each of the targeted colours, must be designed.

Whilst these technological challenges are hurdles that need to be overcome to the design this type of object, it in no way means that it is not feasible. On the contrary, the phenomenon has already been modelled by software, and some prototypes have already been produced. As such, making objects invisible is far from being impossible. In fact, it could be just around the corner!

Interview by Pablo Andres

Swell by an Array of Helmholtz Resonators. Crystals 2021, 11, 520. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11050520↑