Forecasters will be able to identify extreme weather events more quickly and efficiently, thanks to four new imaging satellites and two sounder satellites, scheduled to be launched between 2022 and 2030. These Third Generation Meteosats (or MTGs) will gradually replace the second-generation satellites currently operating in space. The first of these will be launched at the end of this year, to be operational in 2023, followed by three similar models and two sounder satellites.

With them, the images sent to Earth will be twice as accurate and reliable: they will be refreshed every 10 minutes (compared with 15 minutes today), in other words, in near real-time. They will also have a new lightning detection instrument (called the Lightning Imager), never before seen in Europe, which will be able to observe lightning much more accurately than current systems; and operating from the ground so unable to detect lightning between clouds and those about to hit the ground.

They will also be able to detect severe thunderstorms and other extreme weather events at an early stage. These types of events are likely to become more frequent in the future due to global warming. The new observations will improve our knowledge of these events and allow us to warn people when necessary.

One hundred times more data

The data from these satellites – one hundred times more than those obtained by the second-generation satellites – will be used in new models by the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT), the coordinator of the European weather satellite network. In France, the Centre de météorologie spatiale in Lannion, Brittany, is responsible for processing the data. The advantage of this site is that it has good reception, as it is not polluted by other satellite receivers found in larger cities, such as Toulouse, which is the control centre of Météo-France.

The aim is to make the best possible forecasts so that we can prevent and secure people and property.

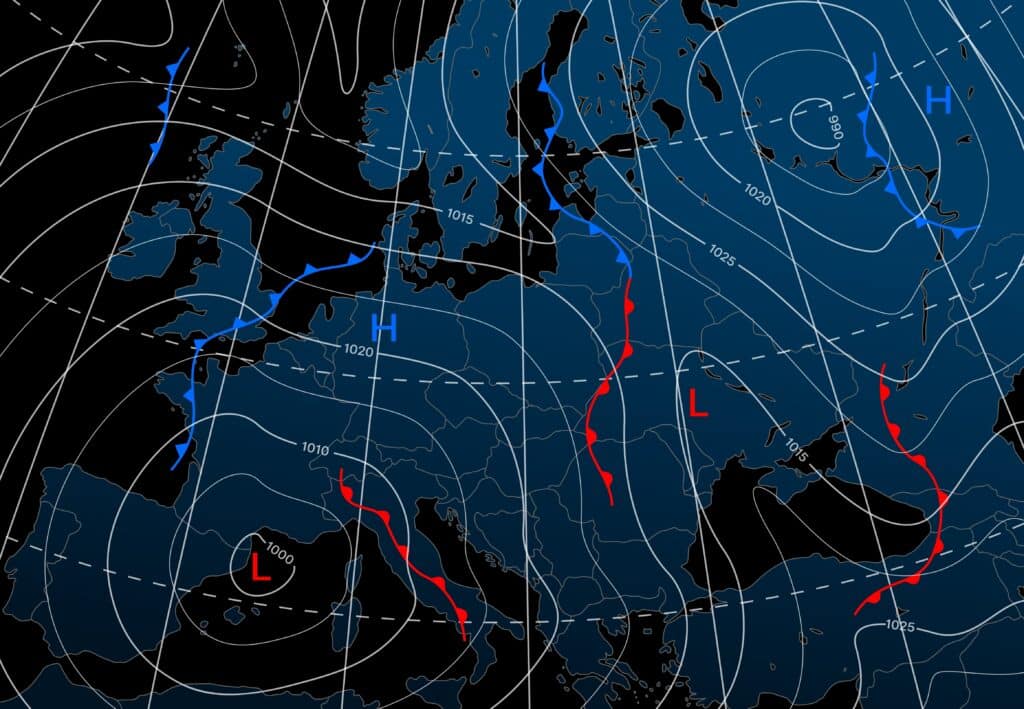

The Second Generation Meteosat (SGM) has an imaging radiometer that operates in the visible and infrared parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. This imager observes the Earth in 12 different channels with a resolution of 1 km for the High-Resolution Visible channel and 3 km for the other channels. Compared to the MSG, we have even more channels with the MTG and more scans, so better accuracy. This information will be useful on a daily basis, especially in high-risk phenomena.

After the launch, there will be a test phase followed by an initial use phase where forecasters will learn to use the new instruments. They should have increasingly rich image and detection quality in several channels, reaching a very high resolution of about 500 metres for the channel operating in the visible spectrum. The aim is to make the best possible predictions to be able to warn and secure people and property.

Multi-spectrum synthetic images

The current Meteosat satellites produce composite and colour images, and the third generation will do the same. The goal for the second and third generations is to create multi-spectrum synthetic images by ‘condensing’ observations from different satellite channels.

There are several types of satellites: firstly, ‘geostationary’ satellites, which always observe the same place on Earth and are located at an altitude of more than 30,000 km. They rotate at the same speed as the Earth and allow us to carry out weather animations. In contrast, the so-called ‘non-stationary’ satellites revolve around the Earth and do not see the same band of trajectory. These satellites are located at a much lower altitude, only 800 km, which makes it possible to obtain much more precise images, especially of low clouds or fog.

By using the different satellite channels, we can make what is called an initial state of the atmosphere. This will allow us to correlate what we observe with what we forecast. To make a good forecast, we need to know what is happening now but also what happened a few days ago, for example, a little further out in the Atlantic. This will allow us to observe the evolution of the cloud masses and to make a good representation of them.

The goal is to create multi-spectrum synthetic images by condensing observations from different satellite channels.

The resulting images are in black and white gradations, a kind of photographic representation of the cloud reflectivity. The bright white colours represent clouds that are generally very thick, as they strongly reflect sunlight. Smaller clouds are greyer, even a little darker, and are often low clouds that are laden with rain and therefore have a low reflectivity, as they absorb more light.

At night, however, we use the infrared channels, which take the temperature of the first layer of clouds encountered. The higher the cloud, the lower the temperature. And the lower the temperature, the lighter the colour. This is why high clouds appear white in the infrared. For a short-term forecast, an animation of several images should be consulted. However, analyses are more difficult at certain times of the year – autumn, for example, when we sometimes find low clouds that have the same temperature as the ground, making them difficult to distinguish.

Interview by Isabelle Dumé

References

https://www.eumetsat.int/mtg-lightning-imager