Organ-on-chip: a mini biotechnology with big ambitions

- Organ-on-chips are microscopic reproductions of human organs.

- These miniaturised systems mimic functionalities, physico-chemical environment and biological processes of human organs.

- Made up of human cells, they combine the experience of a functional system with observation and measurement techniques that are inaccessible in vivo.

- At the crossroads of micro-fluidics, bioengineering and bio-cellular science, these innovations are still being developed.

- Once completed, they will have a vast range of applications, including personalised care, understanding complex processes and observing cell signalling.

Miniaturising the complexity of a functional organ in a small system the size of a domino is no longer impossible. Thanks to a combination of research in micro-fluidics, cell biology and bioengineering, the scientific community has succeeded in creating organs-on-a-chip.

These devices reproduce the functionality, physico-chemical environment and physiological processes of human organs and tissues on a microscopic scale. They are manufactured on plastic or glass surfaces, engraved with different channels and compartments, within which different cell types are cultured and interact. The architecture of these chips makes it possible to imitate the biological processes at work within an organ, such as blood pressure, cell interactions or the speed of fluid circulation in interface tissues (lungs, intestines, kidneys).

The use of human cells also makes it possible to recreate interesting experimental conditions and observe the direct effects – on large organs – of certain mechanical stresses or exposure to therapeutic molecules.

Micro-plumbing, maxi-power

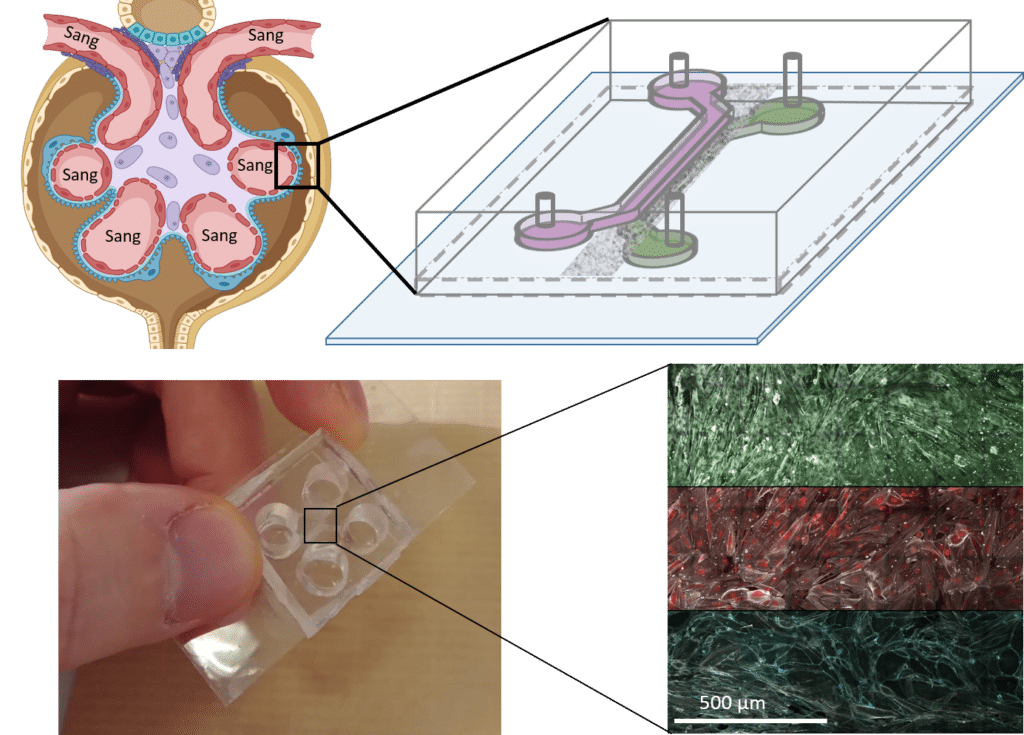

Cédric Bouzigue is a lecturer in biology at École Polytechnique (IP Paris) and a researcher at the Optics and Biosciences Laboratory. He is developing organ-on-chip for applications involving severe kidney disease. “My job is to do plumbing on a scale of a few micrometres”, he smiles. The micro-fluidic systems he designs make it possible to “control signals and circulation, by reconstituting three-dimensional geometries that approximate what happens in a real organ”. As explained below, he is working on a model that reproduces the interfaces between blood and urine in the kidney.

The biologist describes organ-on-a-chip as a theoretically ideal device, as it “makes it possible to reconcile the relevance of a functional system that reproduces the function of an organ, with observation and measurement techniques that are inaccessible in vivo.” As a result, the scientific community can multiply the number of analysis and quantification techniques on a single medium, accurately monitor cell signalling and test the efficacy of different active substances “while varying and controlling the conditions of use and experimentation.” In short, these devices aim to “do better with less,” according to the title of one of the chapters in the book Étonnante chimie (CNRS éditions, 2021).

Clinical trials on chips?

Organs-on chips are still a developing technology. They have not yet taken over the benches of biology laboratories, where experiments are still mainly conducted using cell cultures in Petri dishes or animal models. “Organs-on-chips are not yet sufficiently developed and complex to replace animal models throughout the research process,” points out Cédric Bouzigues.

Nevertheless, the preclinical trials currently conducted to test the efficacy and toxicity of new drugs do not reflect all aspects of human tissue function. What’s more, in a recent report, the US Food and Drug Administration pointed out that nine out of ten drugs fail at the human clinical trial stage, despite having passed the animal testing stage. While no health safety process can – for the time being – match the one currently in place, a technology such as organ-on-a-chip could help to speed up and facilitate the translation of new therapies from the laboratory to humans. For Cédric Bouzigues, “we could validate certain hypotheses on chips initially, before confirming them on living models.”

Hope for kidney infections

Before this technology becomes widespread, biologists from the Optics and Biosciences Laboratory are working with a team from the Paris Cardiovascular Research Center to develop and test models of the renal glomerulus (the kidney’s filtration unit) on microchips. “Glomerulonephritis and segmental or focal hyalinosis are rare kidney inflammations. Without transplantation, these pathologies are fatal”, explains Cédric Bouzigues.

The scientists have therefore designed a glomerulus-on-a-chip system that reproduces the critical mechanisms favouring the onset and progression of the pathology. “Our system-on-a-chip consists of two chambers – urinary and vascular – separated by a membrane made up of glomerular parietal cells.” These cells form the capsule in which the urine is formed. Thanks to an optical imaging device, the scientists can observe what is happening in the chip, at both molecular and cellular level, particularly when it is exposed to active molecules potentially involved in the development of pathologies.

Towards personalised medicine

Organ-on-chip offers promising possibilities. Ultimately, it could be possible to create personalised devices for each patient, depending on their pathology and genetic characteristics. Organ-on-a-chip paves the way for personalised medicine, making it possible to test a patient’s response to a therapy and offer them the possibility of a treatment tailored to their profile.

At the same time, other research teams are working on different types of organ-on-chips, such as vascular systems to study hypertension, or intestine‑, kidney- and lung-on-chip. The materials used to manufacture these devices are generally polymers such as PDMS. They offer high precision and excellent biocompatibility. However, the durability of organ-on-chip remains a challenge, as it is currently difficult to envisage using them to study pathologies that develop over the long term.

Challenges remain, but organ-on-chips are undeniably making their way into the laboratory. The beginnings of a revolution in our understanding of complex biological processes are being felt at both fundamental and clinical levels.