Particle physics in everyday life

- The search for the fundamental components of the universe only began in the 19th Century with Compton and de Broglie discovering the quantum nature of X-rays and the wave properties of particles, respectively.

- One of the techniques of particle physics is based on doping. This involves introducing ‘impurities’ into silicon crystals to modify its electrical properties.

- Another application is in the food industry, where irradiation is used to extend the shelf life of foodstuffs.

- In France, for example, in 2014, 370 000 hectares of sunflower crops - i.e. 56% of production - were grown from seedlings obtained by mutagenesis (gamma irradiation).

- Particle physics is also applied to medicine by making it possible to eliminate cells in the blood in bags used for transfusions but also for medical imaging.

The search for the nature of the fundamental components of the Universe really began at the start of the 20th Century. The “atoms” imagined by Democritus 300 years before Christ really began to be understood when it was realised that contrary to their etymology (a‑tomos = unbreakable, that which cannot be divided into smaller elements), atoms were themselves composed of even smaller elements.

Particles, which, as things stand today, are the most basic elements of matter. But as is often the case in the evolution of science, research that initially served no purpose other than to gain a detailed understanding of the laws of nature and its components has led to applications that have profoundly changed our daily lives. How has particle physics found its way into our daily lives?

The general principle is often the same: direct a beam of particles at a target and study or use its effects. Depending on the type of particle used and the target chosen, the consequences (and uses) will be very different.

Atoms for electronics

Let’s start with something that this article could not have been written without: electronics.

The basic principle of all modern electronics is the use of silicon, which belongs to the class of “semiconductors”. A semiconductor is characterised by the number of charge carriers it has (electrons or electron gaps called “holes”). To increase this number of charge carriers, « impurities » are introduced into the silicon crystal, atoms that add or remove electrons and thus locally modify the electrical properties of the medium. This is called doping.

Doping must be carried out in an extremely precise manner: one part of the silicon crystal must be doped with an excess of electrons while, a few micrometres deeper, another part must be doped with atoms that remove these electrons.

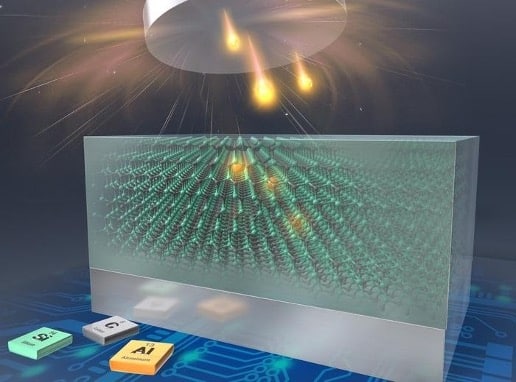

The artificial insertion of these doping atoms can be done by “ion implantation”: they are accelerated by an electric field that gives them a greater or lesser energy, which allows them to penetrate more or less deeply into the substrate to dope certain layers at precisely determined depths.

Irradiation of materials

The irradiation of materials can be voluntary or involuntary. But in all cases, it modifies their microstructure, and this is why it will be used or studied in order to better understand the properties of these materials and their evolution over time.

Ion implantation is a surface treatment process that can also be applied in many situations other than electronics. It allows the chemical composition and surface structure of a material to be modified. Depending on the nature of the substrate and the implanted ion, certain mechanical or chemical properties of the surface (hardness, wear resistance, fatigue, corrosion resistance, etc.) can thus be optimised without changing its main properties.

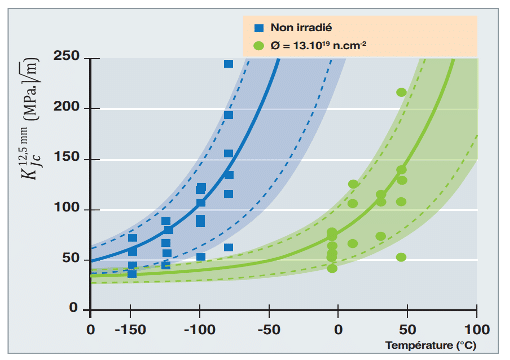

The phenomenon of ageing under irradiation is mainly studied in the nuclear sector. At the heart of today’s nuclear power plants, steel is subjected to intense irradiation from the radioactive fuel rods used to power the installation. The reactor vessel, for example, is a non-replaceable component. It is vital to know and anticipate the ageing of its structure over decades of use.

But this work is also useful for the next generations of reactors, whose temperature and irradiation conditions will be even more demanding than today, not to mention future thermonuclear fusion reactors, such as ITER, whose materials in contact with the plasma undergo intense neutron irradiation.

Particle physics and life

In the food industry, food irradiation is one of the methods used to extend the shelf life of foods. This technique makes it possible to stop the germination process (potatoes, seeds, etc.) and to kill the parasites, moulds, and micro-organisms responsible for the deterioration and/or rotting of food.

To do this, three types of radiation are used: X‑rays or gamma (ɣ) rays (which are two types of electromagnetic radiation, like light, but whose energy is much higher than the part visible to the eye), or electron accelerators.

However, this technique does not completely sterilise food (which still needs to be packaged and cooked properly), but it slows down spoilage and allows it to be stored for longer. It also prevents insects and other pests from laying eggs in fresh produce and destroying them.

Gamma irradiation is also used in agriculture. It is called mutagenesis by gamma irradiation. The principle is to simulate (and accelerate) the process of genetic mutation that occurs naturally in the living world. This technique, which has been used since the 1950s, makes it possible to select new plant strains with favourable mutations (taste, colour, growth, fruit size, etc.).

In France, for example, in 2014, 370 000 hectares of sunflower crops – i.e. 56% of production – were grown from seedlings obtained by mutagenesis. In Texas, 75% of the grapefruits grown are of the Rio Star variety (redder and sweeter), also produced by the mutagenesis process.

Particle physics and medicine

The medical community also benefits from the advantages of electron accelerators in terms of sterilising equipment. The use of radioactive sources of Caesium 137 also makes it possible to treat blood bags using the gamma rays emitted, in order to eliminate certain cells that could cause a fatal disease in patients requiring a transfusion. Saline solutions used to clean and store contact lenses are also sterilised by irradiation.

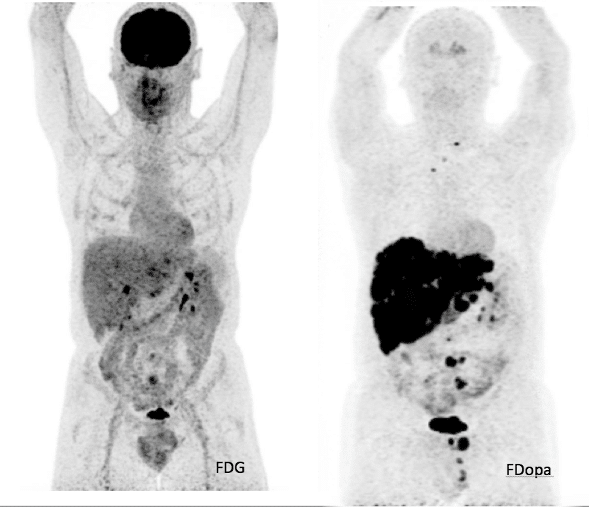

In nuclear medicine, the use of nuclear reactors or particle accelerators allows the creation of radioactive compounds that do not exist naturally on Earth (as they decay in times ranging from minutes to days). However, these elements are very important, both in terms of diagnostic imaging (e.g. Positron Emission Tomography which uses a radioactive element: Fluorine-18 or scintigraphy with Technetium-99) and also in terms of therapy (Iodine 131 for the treatment of thyroid cancer).

Currently, a new technique for irradiating cancerous tumours is being developed: hadrontherapy. This technique uses a particle accelerator to target tumours inside the patient’s body that are difficult to treat with other conventional techniques (often brain tumours). This is an extremely targeted radiotherapy technique, the advantages of which, in terms of precision and patient radioprotection, give reason to hope that, in addition to Germany and Italy, a centre may be built in France in the coming years.