Co-creation in theatre : an antidote to controversy in democracy ?

- Faced with society that is increasingly polarised, researchers are studying how the collective creation of a play can help to re-establish dialogue.

- The project takes the form of artistic productions carried out in 2018 by groups of professionals with opposing views on a controversial issue.

- Their goal was to work together to create a 20-minute play focusing on divisive topics (the use of pesticides in agriculture, the impact of technology on global warming).

- A second survey showed that after the collective creation process, participants had a much better understanding of the context and logic behind each other’s positions.

- Among the limitations of this approach are the ephemeral nature of theatre and the fact that this discipline requires significant resources to be repeated again.

When discussing ecology, politics or various social issues, have you ever felt like you were talking to a brick wall ? The use and misuse of pesticides in agriculture or the role of technology in combating global warming, for example. In an increasingly polarised society, debating with people who do not share our values can sometimes become impossible. This trend is amplified by the proliferation of “echo chambers”1, spaces where we only interact with people who share our beliefs. This has given rise to a new discipline : the sociology of controversy, which studies different points of view and the contexts in which they are expressed. So how can we re-establish dialogue ?

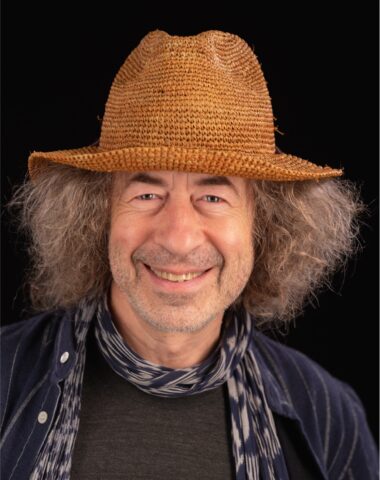

This question is central to the research conducted by Sylvie Bouchet, a doctor of psychology and lecturer at Paris Dauphine University, and Olivier Fournout, a senior lecturer in communication sciences at the Interdisciplinary Institute for Innovation/CNRS at Télécom Paris (IP Paris). In Le Champ des possibles2, they study how the collective creation of a play can help to re-establish dialogue within populations fragmented by intense conflicts. The project takes the form of artistic productions carried out in 2018 by groups of professionals – farmers, environmental activists, entrepreneurs, experts, public and private sector administrators, and association leaders – all actively involved in a controversial issue. The aim was to work together to create 25-minute plays focusing on divisive issues such as pesticides in agriculture and the impact of technology on global warming. Those involved were given free rein to stage their own plays, which they write and perform themselves.

Two years after its creation, half of the participants consider that something has changed in the way they view themselves in relation to the controversy.

The book is accompanied by the results of a survey of participants, which aimed to assess how the joint creative work had “changed their perception of the debate, the other protagonists and the facts of the issue”3. In addition, a second survey4 was conducted in July 2020 to detail the long-term effects of the experience. Among the findings : two years after the creation, “half of the participants (56%) think that something has changed in the way they position themselves on the controversial issue5,” and the multiple levels of change are specified.

What was the starting point for your work, aimed at bringing together people with seemingly irreconcilable opposing views, through theatrical performances ?

Olivier Fournout. The starting point is the observation that in our societies, divisions and controversy are constantly fuelled by the media and social networks. There are divisions and irreconcilable differences. When faced with any reality – even scientific and recognised ones – we are drawn into spirals of violence, both politically and ethically. Different groups of people in conflict no longer talk to each other, or only talk to those who share their views, ignoring what is happening around them. These divided societies are studied by the sociology of controversy.

Based on this observation, my perspective has been to help citizens and students engage with controversial issues in order to understand their underlying causes and try to overcome them. After studying them and sometimes experiencing them first-hand, those involved take part in the creation of a collective theatrical production dealing with the issue. This approach is accompanied by a central research question : how does the process of collective artistic creation change the experience of the people involved ? What can theatre production specifically contribute in terms of representing issues, and how can this be made accessible to the audience ? Thanks to funding from the ANR6, we were able to set up an empirical study of these effects, enabling us to make them the subject of research.

What methodology was used to help people talk to each other, even though they had built their lives around opposing ideas ?

I have used this theatrical methodology more than 150 times : with students and citizens, but also, on several occasions, with professional actresses on the subject of transhumanism7. The collective creation process is well established. A 50-minute documentary filmed in 2018 recounts this process8. Each time, we start with a societal phenomenon that has been studied and/or experienced. The creation time is short. In two days, the participants create a 20–25-minute play and perform it in front of an audience. There is a lot of improvisation, including in the final performance. People who, in most cases, have never done theatre before can find themselves at ease improvising and performing very accurately, in a very lively and natural way, as opposed to reciting a text they have learned by heart. The staging choices, acting and text are left entirely up to the creative groups. The facilitators provide feedback, but the group and its collective dimension always have the final say. The rules of the game are shared with the group in advance, and creativity flourishes within this framework. I tested this collective creation format for the first time in 2009, in a highly innovative course for the Corps des Mines, combining field geology, theatre and observation of group dynamics. This course, which still exists, gave rise to a paper in educational sciences in 20119.

You start with a variety of controversial topics : pesticides, the relationship between technology and global warming, the marriage equality movement, and more. How do these people experience controversy in real time ?

To return to the issue of marriage equality, we published a research paper in 2017 with Valérie Beaudouin on this theatrical production that was staged in 201310. What was particularly striking about the group of students who took part was that most of those who had voluntarily signed up to dramatise this controversial issue were deeply concerned about the subject. Students came to sign up saying that they could no longer discuss it among themselves and wanted to open up the dialogue. That’s why they signed up, and one student in particular confided that she felt very deeply about the subject. This lent a special tone to the work done by this group of students, because it wasn’t just about studying the issue. The creative process brought something deeply felt to the surface.

For questions about pesticides and whether technology helps or hinders the fight against climate change, we had the means to conduct a survey and objectively assess the effects on the participants in the collective creation. The play on pesticides featured an organic farmer, another who treats his more than 100 hectares with glyphosate, a technical advisor for large farms, an environmental activist, the head of an association, a doctor registered with an agricultural health insurance fund who is himself a winegrower. With this panel, we achieved the highest possible level of representation on the subject. It was challenging and uncompromising, because there was a real divide at the outset, with participants afraid of being attacked. For example, the farmer who sprayed his fields with glyphosate thought he was going to be “lynched”. In a way, we have an empirical breeding ground where we start from a very distant point in terms of division and the risk of hurt feelings.

For the play on marriage equality, we were unable to conduct a survey of students on the collective creation process at the time, but the content of the play itself reflects very positive results. Although they didn’t agree with each other at all, the students managed to draw a frieze with six different representations of couples, which were projected during the play and which Valérie Beaudouin and I reproduced in our article. In a way, the play gave birth to a model of diversity, even though the students disagreed about these representations in the public space. Another achievement is the name the theatre company gave itself, “theatre for all”, which neatly sums up the unifying power of theatre, in the same way that a Shakespeare play brings together Falstaff and the future Henry V in a tavern. In short, the students managed to find common ground through theatre, where the subject matter was divisive, which is both touching and effective.

Finally, in the case of your studies on pesticide and technology issues in relation to ecology, did people “change their minds”?

Changing people’s minds is not something that can be set as an imposed objective. What we observed in our second survey conducted in 2020 was that, after the collective creation process, there was a much better understanding of the context and logic behind other people’s positions, a sensitivity to personal stories and an openness to dialogue with people with whom it had previously been impossible to discuss these issues. From exposure to opposing positions, initially perceived as the worst enemies in the conflict, empathy and emotion eventually emerge, which is a fantastic result. Fantastic, because this initial result paves the way for cognitive advances : two years after the experiment, 70% of participants said they had learned things in terms of “reflection” and “thoughts”.

The key point here is undoubtedly the process of theatrical creation, which brings together people who no longer talk to each other in real life and creates a common object around which dialogue can take place. Indeed, the controversial elements of the play, such as the theme of pesticides, are intertwined with the obligation to create a play together. This obligation, which is stronger than the subjects of disagreement, makes it possible to rebuild relationships, or to build what I call in the book a “relational ecology”, which becomes the condition for any real progress. In short, we must first work on the ecology of human relations to achieve results in the ecology of nature, which requires everyone’s contribution in the search for solutions. The theatrical process makes it possible to restore a form of alliance to successfully co-create the play – a play which is itself a dialogue that addresses the root of the problem.

Did you encounter any limitations in your approach ? In your 2020 survey, participants told you that they would have liked to have received support over a longer period of time, after the two collective theatre productions in 2018. How do you analyse this limitation of your work ?

One of the limitations of the approach is that theatre is a very ephemeral discipline that requires a lot of resources to be performed again. For example, we staged two plays in the Deux-Sèvres region, in partnership with a CNRS agroecology “Zone Atelier” (Centre d’Étude Biologique de la Forêt de Chizé) and WISION, a company specialising in mediation in rural areas. The subject was the relationship between farmers and local residents. The plays were created and performed by farmers and local residents, joined by a few students. The two plays we filmed11 went very well, and we parted ways saying that we should perform them again. However, the will and resources to do so are not necessarily there, and finding venues is difficult. It is a very powerful process on an existential, emotional and affective level, involving the body, but one that is not easily repeated.

We need mechanisms that work on relationships in order to then work on changes in practices and values.

In 2020, in the midst of the COVID lockdown, we set up a dialogue platform called ZigZagZoom12 with Cyrille Bombard, who works as a social mediator. We bring together three people in favour of a position and three people against it, with a participatory audience of ten to fifteen people. We always come to the same conclusion : changes in behaviour and attitudes can only come about if we first work on the relational groundwork. This result is probably generalisable. It is not expert discourse, however numerous and competent, that brings about change. If it did, many problems would already have been solved. What does bring about change, however, is first and foremost building relationships based on mutual understanding. We need mechanisms that work on relationships to then work on changing practices and values.

The participants in our 2020 survey were disappointed by the framework of the experiment, which they had expected to support them after the collective theatre experience. This is indeed a limitation that I have not been able to address, as the research is highly dependent on funding that is limited in time and per project. When funding stops, there is no follow-up because resources are suddenly cut off. For example, I can no longer work with my colleague, a social mediator who would like to continue the effort to anchor the changes that have been initiated and keep the programme alive over the long term.

Do you think, more broadly, that fiction can contribute something to our societies ? We often think that fiction invents, and therefore divides…

In our 2018 play about pesticides, a new mythological character appeared : “the little sick field”. This character was created by the troupe. It is not mentioned in any of the encyclopaedias of the imagination that I have consulted. It is a creation from this play which may one day change the world. Placing a fictional device such as “the little sick field” at the centre of the story is already a way of learning how to heal it. Seeing is already doing, as research on mirror neurons tends to show13. Thus, fictional actions on a theatre stage, especially when they have been created by the very people involved in society’s problems, open the way to overcoming divisions. They inspire us to build a common future together. This is undoubtedly a necessary and essential condition for solving problems.