With the link between (internal) language, thought, and self-awareness being established, the question arises as to whether deprivation of this ability affects cognitive and metacognitive functions. In some cases of non-fluent aphasia, partial or complete loss of the ability to speak aloud because of brain lesion, internal speech is also affected. In these cases, cognitive and memory problems are often also observed. However, these disorders are not necessarily due to the deficit in inner speech, as the brain lesion itself can affect several cognitive processes.

What can be learned from late-talkers?

A piece of the puzzle can be found in studies of individuals who started talking late in childhood, the famous “late-talkers”. A famous case is that of Albert Einstein, who is said to have had a language delay in childhood. In these individuals, can concepts still emerge and be manipulated mentally, with a poorly developed sense of language?

The mathematician Jacques Hadamard recorded Einstein’s testimony on his cognitive functioning1. When asked about the mental images or forms of “inner words” he employed in thinking, Albert Einstein replied, “the words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be ‘voluntarily’ reproduced and combined.”

Thus, Einstein’s use of language only came at a second stage, in which he had to “translate” his thoughts into words for others. It is not clear whether this non-verbal mode of thinking is causally related to his late onset of speech, but it does reveal that a form of conceptual thinking can take place without language. It is even possible to consider that thinking can sometimes take place in some individuals not only without language but also without visual images and physical sensation. Indeed, recent research in cognitive science reveals that mental representations are sometimes amodal, or abstract.

Thinking can sometimes take place not only without language but also without visual images and physical sensation.

Thinking without images or sound

The nature of mental representations has long been the subject of debate, between proponents of embodied, or somatosensory, cognition and defenders of the abstract mentalist conception. These debates have been rekindled recently by the observation of atypical forms of mental imagery.

In 2010, the neurologist Adam Zeman and his team reported the case of a patient who lost the ability to voluntarily visualise after an angioplasty2. His mental visualisation deficit was not accompanied by any visual recognition or other impairment. For example, he was able to describe his city perfectly, but was unable to picture it in his mind. Zeman’s article received a lot of media attention and many people spontaneously reported that they were born without visual imagery. Surveys then revealed that a significant proportion of the general population appears to lack voluntary visual mental imagery innately.

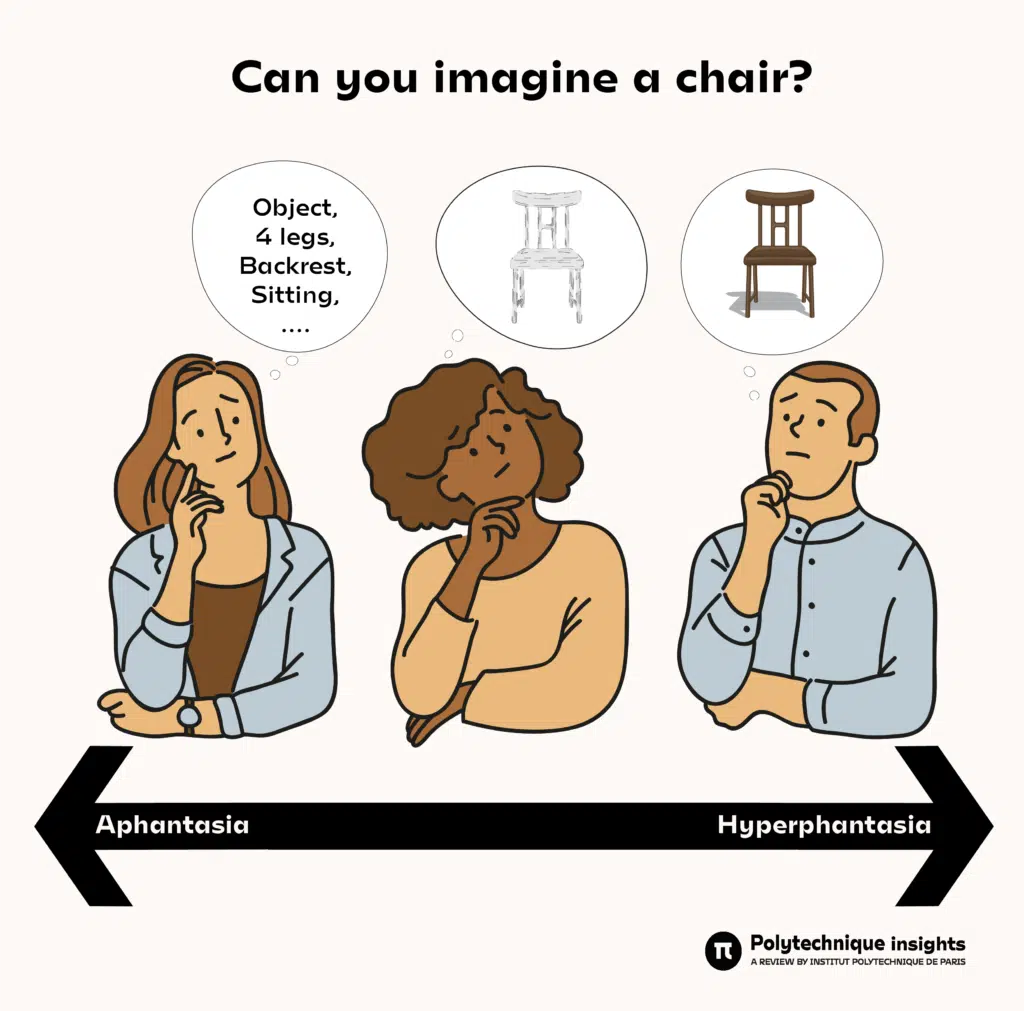

In 2015, Zeman and his team therefore introduced the term ‘aphantasia’, from the Greek φαντασία (“imagination”), to describe this specific lack of mental imagery3. It has also emerged that the inability to voluntarily create mental images can extend to other senses: sounds, smells, tastes, touch. There is still no objective test to know whether one has aphantasia or not, but some recent experiments seem promising. For example, researchers have shown that priming biases in mental imagery that are usually observed when presented with ambiguous visual stimuli are absent in people who self-report aphantasia. Furthermore, neuroimaging studies have revealed patterns of neural activation modulated by the strength of individual visual imagery. Taken together, these results suggest that aphantasia may be a genuine absence of sensory correlates during mental representation.

At the Laboratoire de Psychologie et NeuroCognition in Grenoble, we launched a large online study on this topic in July 2021. The study is still in progress and can be conducted in English or French45. It includes questionnaires on mental representations and imagery and an audio perceptual test. We have recruited our participants very broadly and by targeting the networks of people concerned with aphantasia. To date, out of approximately 1,000 participants, we have already identified 200 people whose responses to the questionnaires suggest aphantasia. Some of these people report that they can speak to themselves internally, but that their inner language is not aural: it is just words, no voice sensation, no intonation, no visual image of written words or gestures (of sign language). In contrast, our survey revealed that some people have auditory verbal hyperphantasia, i.e. an ability to generate very loud, vivid and clearly sensory inner verbalisations6.

Inner speech without auditory or visual sensation, auditory and visual verbal aphantasia, represents a challenge to current theories of cognition and language. Can we access words without their sound, their spelling, or their sign? Research in psycholinguistics suggests that there is a level of representation, the lemma, in which we have access to certain characteristics of the word, without having the phonological form, the sound, in mind. This is the “tip-of-the tongue” phenomenon. When speaking, we can sometimes remember certain details of the word we are looking for, like the number of syllables, the consonant with which it begins, without being able to say it to ourselves in its whole form and therefore to mentally simulate its sound.

At the other extreme, hyperphantasia, the ability to hear voices in one’s head as clearly as in reality, raises the question of the limit between mental imagery and hallucination. How can we avoid confusing the imagined voice with a voice actually perceived?

Some studies seem to postulate that aphantasia is a disorder, but recent research suggests rather that it is simply a specific mode of operation, an atypical mental functioning. So, the question remains unresolved. As does the question of whether hyperphantasia is an advantage or a disadvantage, especially when flashbacks or imagined sensations become too intense. There is still little research on the consequences of atypical forms of mental imagery. It can be assumed that people with aphantasia process information in a more semantic, factual, or descriptive way, whereas people with hyperphantasia would engage in more detailed sensory processing. The practice of inner language in these two atypical populations probably gives rise to very different representations of the self and it can be hypothesised that self-awareness is itself constructed in an extremely varied manner. It is therefore important to continue to explore the diversity of forms of inner language and to survey as many individuals as possible.

Take part in our online survey and further the research!